Poet Emily Dickinson’s recipe for a prairie was a clover, a bee, and revery. No doubt she’d call for a muskrat when making salt marsh salt marsh

Salt marshes are found in tidal areas near the coast, where freshwater mixes with saltwater.

Learn more about salt marsh .

In Chesapeake Bay, this small cousin of the beaver is a valuable partner in an ambitious project to restore a remote island under siege. It’s helping turn sediment scooped from Baltimore shipping channels into healthy salt marsh habitat.

Location changes everything

Poplar Island was one or two strong storms from going the way of more than 400 Chesapeake Bay remote islands in as many years. Once more than 1,100 acres and home to a year-round community, it was down to a handful of acres, beset by erosion, sea-level rise, and sinking. A mile off Maryland’s eastern shore, it no longer buffered the mainland from waves blown across the bay.

Thirty-five miles to the north, the Patapsco River enters Baltimore Harbor as it has for millennia, depositing silt and sand gathered in its 40-mile trip through central Maryland. To keep the Port of Baltimore open to the largest cargo ships, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) and the Maryland Department of Transportation Maryland Port Administration (MDOT MPA) remove about two million cubic yards of sediment a year.

The same silt that clogs a port can rebuild an island. Since the mid-1990s, barges have carried the dredged material down the bay to the Paul S. Sarbanes Ecosystem Restoration Project at Poplar Island, where it’s used to recreate the island. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service partners with USACE and MDOT MPA on the ambitious undertaking.

The rebuilt Poplar Island, showing containment cells at various stages of restoration: some with plants and water, some with bare soil, and some with water. The small, separate islands are remnants of the original island. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

At the island, the sediment is mixed with water and piped into cells formed by containment dikes. Once a cell is full, heavy equipment shapes the landscape into natural features. When complete in 2043, the island will be about 1,700 acres, with equal parts tidal salt marsh and upland habitat.

Staff at the Service’s Chesapeake Bay Field Office in Annapolis helped design the project. They track wildlife populations and vegetation growth on the reconstructed island. They also count waterfowl, shorebirds, and songbirds and manage predators.

“We’ve been involved from the start, and we’ll be here after the last barge leaves,” said Pete McGowan, the Service’s lead wildlife biologist for the project.

The salt marsh’s secret sauce

There’s more to making a salt marsh than soil and plants. By definition, seawater must move through the marsh in daily and monthly cycles driven by the tide. Muskrats put the finishing touches on the restoration.

Although perhaps less intentional than their well-known cousins, muskrats also shape their surroundings. While beaver dams flood the landscape, killing trees and creating freshwater marshes, muskrats eat their way through salt marshes, helping other wildlife and strengthening the habitat.

“They engineer the ecosystem just as beavers do,” said McGowan.

Muskrats eat marsh grasses, such as smooth cordgrass and marsh hay, and the roots of shrubs like high-tide bush. They consume one-third their weight every day, opening areas of dense vegetation, keeping troublesome plants from taking over, spreading nutrients, and aerating the soil.

Perhaps most important to restoration, muskrat trails — called leads — move water throughout the salt marsh. Marsh plants are adapted to the coming and going of the tide, and they can’t survive constant flooding.

“Water gathers in areas where sediment has settled,” said McGowan. “Muskrat leads drain interior pools and keep vegetation from standing in water for long periods.”

Leads also let marsh birds like ducks and rails travel more easily and save energy. Small fish and invertebrates can reach ponds in the marsh’s interior.

And so, it turns out, can turtles. Researchers from Ohio University recorded as many as 1,500 diamondback terrapin hatchlings in one year on Poplar Island.

“A great variety of wildlife uses these biological highways,” said McGowan.

In addition, muskrat huts, which are three- to four-feet high, add what biologists call microtopography to the marsh. On Poplar Island, muskrats build their mounded homes from salt meadow hay and salt marsh cordgrass.

Smaller rodents like shrews and voles find shelter in the huts, and turtles climb on top to bask in the sun. Raptors such as short-eared owls and northern harriers rest atop the houses, where they scan the marsh for their next meals. Mallards and Canada geese sometimes build nests on the mounds.

Moderation is key

You can, however, have too much of a good thing, and muskrats are no exception. As the population grows, so too do the odds of disease, starvation, and conflict over territories. At a certain point, they start to harm the very habitat they — and so many others — depend upon.

With no mammalian predators to keep them in check, muskrat populations on Poplar Island tend to be cyclical — numbers increase for a few years, stressing the habitat, then crash due to disease. To reduce habitat damage, biologists manage the animals.

First, they need to know how many muskrats there are.

In Winter 2007, a team of biologists and volunteers randomly chose 20 muskrat huts in each marsh and trapped the occupants until no more appeared. By dividing the total number of muskrats by the number of huts, they found the average number of animals per hut, which was 4.6.

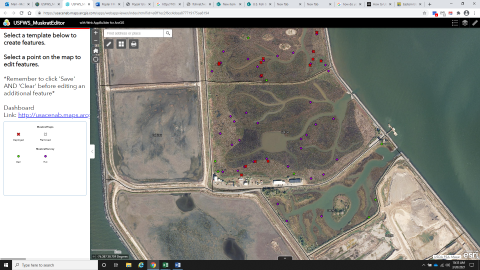

They’ve returned every year since. With a smartphone app called Collector, they plot muskrat huts on Geographic Information System (GIS) maps created with help from USACE. Using the average occupancy rate, they estimate the muskrat population in each marsh.

Next, they need to know how many muskrats the marsh can support.

For this, McGowan uses a computer model created by the Service. It takes data collected by the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science at nearby Horn Point Laboratory and estimates the amount of plant material — both above and below ground — in a marsh. It then calculates how many muskrats can live there without harming the habitat — the marsh’s muskrat carrying capacity.

“To keep the system in balance, the model allows for muskrats to remove no more than four percent of the plant biomass,” said McGowan. “The model calculates the carrying capacity of the marsh and, if the muskrat population exceeds it, tells us how many need to be culled.”

Service staff remove the extra muskrats through trapping. It’s not necessary every year, and the numbers are usually low.

A recipe for success

More than two decades into the Poplar Island project, the results are impressive.

The number of bird species has increased from fewer than 11 to more than 300. Thirty-four species now nest there, including American oystercatcher, glossy ibis, and snowy egret. The island hosts the largest least tern colony in Maryland and the largest common tern colony in that state’s portion of the bay.

Internationally recognized as a model in island restoration, the project draws scientists from around the world to learn from those involved.

The public can also visit, through tours offered by the Maryland Environmental Service. When restoration is complete 20 years from now, the island will be managed by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources or another natural resource agency, perhaps the Service.

Because the Port of Baltimore will always need dredging, restoration partners have set their sights on the next lucky recipients of dredge material. The Mid-Chesapeake Bay Island Ecosystem Restoration, which will rebuild Barren and James islands, is in the design phase, and Service staff will count small mammals and birds there this summer. Barren Island is part of Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge.

Thanks to one hungry rodent, some creative state and federal agencies, and an unlimited supply of sediment, Poplar Island is once more a destination for migratory birds and people alike. It also protects Maryland’s eastern shore from westerly waves. Its recipe for successful remote island restoration is being cooked up worldwide.