States

Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, VermontThe 2009-2019 Wetlands Status and Trends national report is the 6th in a series of congressionally mandated reports spanning nearly 70 years. It provides scientific estimates of wetland area in the conterminous United States as well as change in area between 2009 and 2019. The report also discusses drivers of wetland change and recommendations to reduce future wetland loss.

Key Findings

In 2019 there were an estimated 116.4M acres of wetlands accounting for less than 6% of land area within the conterminous U.S. The vast majority of these were freshwater, accounting for 95% of all U.S. wetlands. Most wetlands were vegetated, including 92% of freshwater and 80% of saltwater wetlands.

- Wetland loss increased by more than 50% since the previous study.

- 221K acres of wetlands were lost, primarily to uplands through drainage and fill.

- Wetland loss disproportionately affected vegetated wetlands, resulting in the loss of 670K acres of these wetlands.

- Salt marsh experienced the largest net percent reduction of any wetland category (2% or -70K acres) while freshwater forested experienced the largest loss by area. (-426K acres)

- There was a net gain in non-vegetated wetlands of 488K acres, and a related increase in pond area of over 7%.

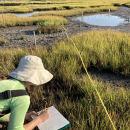

Our Nation’s remaining wetlands are being transformed from vegetated wetlands, like salt marsh salt marsh

Salt marshes are found in tidal areas near the coast, where freshwater mixes with saltwater.

Learn more about salt marsh and swamp, to non-vegetated wetlands, like ponds, mudflats, and sand bars.

Impacts of Wetland Loss

Wetlands provide numerous life-sustaining benefits that are vital to the environment as well as human health and well-being. Loss of wetlands contributes to a decrease in human safety, health, and economic prosperity due to increased susceptibility of people and infrastructure to natural disasters, decreased food and water security, increased harmful algal blooms and greater vulnerability to sea level rise.

Wetland loss also negatively impacts fish, wildlife, and plant populations that rely on them for survival, leading to a growing list of threatened and endangered species and threatening our culturally, commercially and recreationally valuable species. The full impact of wetland loss may not be evident immediately, and it may decades, centuries, or longer before restored wetlands function like natural wetlands if ever, highlighting the importance of reducing future losses.

“The impacts of wetland loss, gain, and change on the functions and services provided by wetlands are cumulative over space and time and may be difficult to reverse."

Significance of Vegetated Wetland Loss

Vegetated wetlands function differently than non-vegetated wetlands and often provide more ecosystem benefits. These benefits include building resilience to storms and sea level rise, enhancing water quality by trapping sediment, oxygenating the water column, removing pollutants, regulating climate by trapping carbon dioxide and storing carbon, and providing vital habitat for imperiled and commercially valuable species.

The effects of vegetated wetland loss are highlighted by recent species population trends including those documented in the North American State of the Birds report. The report documented that one-third of water birds are experiencing population declines including several rail species that rely almost exclusively on vegetated wetlands. In addition to these rail species, other “Tipping Point” species (i.e., cumulative population loss exceeded 70% since 1980) include the seaside and saltmarsh sparrow, which also rely heavily on vegetated wetlands, and 1/3 of shorebirds. Alternatively, diving and dabbling ducks that use open water habitats were shown to have stable or increasing populations.

Drivers of Wetland Loss

The losses documented by this study extend a long-term pattern of net wetland loss within the conterminous U.S. During the mid-1900s, net loss was dominated by drainage and fill, primarily associated with agriculture. By the late 1900s, urban and rural development was associated with over half (53%) of net wetland loss, followed by agriculture (26%) and upland forested plantations. While drainage and fill remain the main driver of wetland loss within this study period, other less direct mechanisms are also important, including those associated with the effects of climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change . Different drivers often interact, accelerating loss.

Strategies to Reduce Wetland Loss

To achieve no net loss of all wetlands, including vegetated wetlands, a strategic update is needed to America’s approach to wetland conservation. Four foundational strategies were identified to help address wetland policy, management, and science gaps.

- Achieve “No Net Loss” of wetlands and robust coordination with government and non-governmental partners.

- Produce a contemporary NWI Geospatial Dataset and spatially explicit information on wetland function.

- Develop and implement enhanced wetland conservation and management approaches based on a holistic review of current and past actions.

Commit to long-term adaptive conservation, management, and monitoring.