States

AlaskaEcosystem

Tundra, WetlandOverview

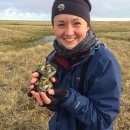

Shorebirds are quickly declining in North America. To better understand what's affecting shorebird populations, in 2003 we established a long-term study of the breeding ecology of shorebirds at Utqiaġvik (formerly Barrow), Alaska. Each year, a group of biologists, volunteers, and students work in the tundra surrounding Utqiaġvik finding hundreds of nests, banding hundreds of shorebirds, and collecting various environmental data (e.g. snowmelt, invertebrate abundance, predators). Our long-term goal is to understand how local environmental conditions influence shorebird ecology and demography, helping us understand what drives population trends.

We study a wide range of topics at this site, including the collection of long-term shorebird breeding data, focused breeding and migration studies on the arcticola Dunlin, experimental nest studies, measurements of contaminant levels in adults and eggs, and tests on emerging technologies to decrease our impact. These studies have allowed us to document long-term trends in shorebird diversity and abundance, timing of nesting, nest and chick survival, adult survival, mate and site fidelity, and both environmental and human effects on shorebird productivity and survival. Ultimately our goal is to evaluate the adaptability and response of shorebirds to climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change . We frequently combine and compare our results to others working across Alaska and Canada, increasing our work and other's impact to shorebird science. In addition to our scientific pursuits, our long-term site in Utqiaġvik, Alaska provides a unique opportunity for participating in the community's Migratory Bird Festival, and for having artists and photographers to visit and document arctic field work in Alaska.

Importance of this Work

Many factors across a shorebird's breeding, migration, and wintering range can affect their survival. For most shorebirds, we don’t know what is limiting their population growth. Long-term studies are critical in revealing patterns and trends throughout time, as environmental conditions across their annual cycle are likely to differ from year-to-year. This long-term study provides ample opportunities to support graduate student projects and provide experience and training to early-career biologists, building capacity in shorebird science across Alaska. Our Utqiaġvik field site provides a welcoming place for numerous studies by MSc. and PhD students working with academic advisors at universities across the United States and Europe.

Projects throughout the years:

- Adult and egg size variation through time in relation to environmental conditions (Hunter Wells, Iowa State University)

- Pre-breeding movements of Dunlin in relation to roads and snow melt (Aaron Yappert, MSc, Iowa State University)

- Behavioral ecology of Red Phalarope (Johannes Krietsch, PhD, Max Planck Institute for Ornithology)

- Migration ecology of Dunlin (Ben Lagassé, MSc, University of Colorado Denver and PhD, University of Alaska Fairbanks)

- Effects of mate and site fidelity on Dunlin reproduction and adult survival of Dunlin (Lindsay Hermanns, MSc, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University)

- Effects of human disturbance on nest survival (Sarah Hoepfner, MSc, Iowa State University).

- Replacement nesting and morphological differences in Dunlin subspecies (River Gates, MSc., University of Alaska Fairbanks)

- Adult and brood survival of Dunlin (Brooke Hill, MSc., University of Alaska Fairbanks)

- Post-breeding movement of shorebirds along the coastal lagoons and estuaries of the Arctic Coast (Audrey Taylor, PhD, University of Alaska Fairbanks)

- Estimation of adult arrival in Dunlin using stable isotopes (Andy Doll, MSc., University of Colorado Denver)

- Nest site selection based on habitat and social cues by shorebirds (Jenny Cunningham, MSc. University of Missouri Columbia)

- Nest reuse by shorebirds (Patrick Herzog, MSc., Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Germany)

- Avian malaria in shorebirds (Claudia Ganzer, PhD, University of Florida Gainesville)

- Avian microbiota in shorebirds (Kirsten Grond, PhD, Kansas State University)

- Cross-seasonal effects on population trends of Semipalmated Sandpipers (Megan Boldenow, MSc., University of Alaska Fairbanks)

- Assessment of shorebird chick diets using DNA metabarcoding (Danielle Gerik, MSc., University of Alaska Fairbanks)

Replacement nesting and enumeration of Red Phalaropes (Jillian Cosgrove, MSc., Oregon State University.

Actions WE ALL can take

Giving them Space. Beach/coastal walking, a seemingly harmless activity, can have negative consequences on shorebirds that are using the area for rest, foraging, or nesting. In some parts of the U.S., human disturbance is one of the most significant threats to shorebird populations. These threats can intensify as human use (coastal recreation, off-leash dogs) in these coastal areas increases, leading to an overall reduction in suitable, undisturbed habitats for shorebirds.

If you are recreating near a coastline, shoreline, or other wetland type used by shorebirds, please give the shorebirds space—ideally, do not approach within 200 m (656 ft.). If you are recreating with a dog, please keep your dog leased, as the presence of dogs is directly related to shorebirds expending more energy being alert to their presence. If you are located in Anchorage, the municipal law requires you to restrain your dog in public places unless you are in a designated off-lease dog park. Learn more about how leashing your dogs protects birds from the National Audubon Society.

Participating in citizen science. Anyone can contribute valuable data by submitting what they see to citizen science programs like eBird or becoming an International Shorebird Survey volunteer. Shorebirds lend themselves to being quite visible outside the breeding season, congregating in large flocks and utilizing visible habitats like beaches and shorelines. Casual bird sightings can be a valuable data points for scientists. By submitting your bird sightings to eBird, or participating in the International Shorebird Survey you can play a crucial role in helping scientists monitor shorebirds.

Spreading the Word: Share information about shorebirds and their threats with your family, friends, and neighbors. Talk to them about how sustained public support are crucial to ensure the future of this group of birds.