About Us

Malheur National Wildlife Refuge was established on August 18, 1908, by President Theodore Roosevelt as the Lake Malheur Reservation. Roosevelt set aside unclaimed government lands encompassed by Malheur, Mud, and Harney Lakes “as a preserve and breeding ground for native birds.” The newly established “Lake Malheur Reservation” was the 19th of 51 wildlife refuges created by Roosevelt during his tenure as president. At the time, Malheur was the third refuge in Oregon and one of only six refuges west of the Mississippi.

Today, Malheur consists of more than 187,000 acres, a tremendously important source of wildlife habitat. The Refuge represents a crucial stop along the Pacific Flyway as a resting, breeding, and nesting area for hundreds of thousands of birds and other wildlife. Scroll down to learn more About Us - OUR MISSION, PURPOSE, and HISTORY.

Our Mission

Malheur National Wildlife Refuge is part of the National Wildlife Refuge System, a network of over 560 refuges set aside specifically for fish and wildlife. Managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Refuge System is a living heritage, conserving fish, wildlife, and their habitats for generations to come.

Our Purpose

August 18, 1908 Lake Malheur Reservation (Malheur, Mud, and Harney Lakes) was established by President Theodore Roosevelt “as a preserve and breeding ground for native birds.”

1935 The Blitzen Valley addition was formally added to the Lake Malheur Reservation by President Franklin D. Roosevelt “as a refuge and breeding ground for migratory birds and other wildlife.” At the same time, the name of the reserve was changed to Malheur Migratory Bird Refuge.

1941 The Double-O Unit was added to the Refuge “as a reservation for migratory birds.”

1975 Harney and Stinking Lake Research Natural Areas were established. Harney Lake RNA was established to “exemplify southeast Oregon alkaline lakes (playas) and associated vegetation and wildlife.” The RNA for Stinking Lake was to “preserve an example of a small, spring-fed alkaline lake southeast Oregon and the associates high desert vegetation and wildlife.”

2008 The Refuge was selected and approved as an Important Bird Area (IBA) by the Audubon Society. The Refuge was designated as a site that provides essential habitat for one or more species of birds and is recognized as being important on a global, continental, or state level.

2013 Malheur National Wildlife Refuge completed its Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP). The CCP describes priorities for the Refuge and how decisions will be made over the next 15 years.

Our History

For thousands of years, people have been drawn to Malheur's abundant wildlife and natural resources. Malheur National Wildlife Refuge is committed to protecting these resources of plants, animals, and human interactions with each other, and the landscape over time. Scroll down to learn a little more About Us - GEOLOGY AND GEOMORPHOLOGY, NATIVE AMERICAN USES, FUR TRAPPERS, SETTLING THE LAND, SETTING ASIDE LAND FOR WILDLIFE, and CIVILIAN CONSERVATION CORPS (CCC).

The lack of available food and a scarcity of fur-bearing animals around the lakes led to the name “Malheur” the French word for misfortune.

Geology and Geomorphology

Malheur National Wildlife Refuge is an oasis in the high desert of southeastern Oregon for the multitude of birds and other wildlife who make it their home. Situated in the wide open spaces of the Harney Basin on the northern edge of the Great Basin, the Refuge encompasses a mere 292 square miles of the 5,300 square miles covered by the basin. The Refuge includes vast cattail and tule wetlands, lakes, dry alkali playas, ponds, greasewood covered flats, lush native grass meadows, long corridors of riparian riparian

Definition of riparian habitat or riparian areas.

Learn more about riparian vegetation, and sagebrush sagebrush

The western United States’ sagebrush country encompasses over 175 million acres of public and private lands. The sagebrush landscape provides many benefits to our rural economies and communities, and it serves as crucial habitat for a diversity of wildlife, including the iconic greater sage-grouse and over 350 other species.

Learn more about sagebrush covered hills bordered by impressive basalt rims. This great variety of wildlife habitats encompassed by the Refuge begins in the lowest elevations of the basin and expands southward along the Donner und Blitzen River to the base of Steens Mountain and northwest into the lower reaches of the Silver Creek drainage.

Three shallow playa lakes, Malheur, Mud, and Harney, are located in the lowest portion of this vast basin and receive life-producing water from the surrounding hills and mountains. Most of the water reaching the lakes arrives in the spring as snow melts and flows southward down the Silvies River, northward in the Donner und Blitzen River, and through the Silver Creek drainage from the northwest. With an average annual rain/snowfall of only nine inches, a drought year can result in extremely dry conditions, reducing the lakes to a mere fraction of their former size or becoming alkali-covered playas. The area surrounding the lakes is relatively flat, so a one-inch rise in the water level will put almost three square miles of adjacent land under water. An extremely abundant year of rain and snow can force water to rise beyond the boundaries of the Refuge to cover surrounding lands - doubling or tripling the size of the marsh. In the mid-1980 three years of above-normal snow forced Malheur Lake beyond the Refuge boundary; the lake grew from 67 square miles to more than 160 square miles. The reverse is also possible: in 1992 Malheur Lake shrank to 200 acres.

The climatic and geologic conditions in this portion of Oregon have changed significantly over time. Nearly ten million years ago tectonic faults and regional uplifting began the formation of Steens Mountain on the south side of the Harney Basin. Eventually, rising 9,700 feet above the surrounding valleys, Steens Mountain developed a vast ice field covering the upper reaches of the mountain around one million years ago. More recent glaciers carved the spectacular U-shaped gorges on the flanks of the mountain. As the glaciers slowly moved downhill, their weight and movement ground the rock below into a fine powder, or loess. This loess was captured in the numerous streams flowing from beneath the glaciers and carried down the Donner und Blitzen River and other creeks on the western flank of the mountain to be deposited on the flood plain of the Blitzen Valley. Turbulent down slope winds pushed these deposits of loess around the valley floor, eventually forming a series of low, vegetation covered dunes at the south end of the river valley.

Native American Uses

The abundance of birds, animals, and plants found in the Harney Basin provided Native Americans with plenty of food and resources for over 11,000 years. Use of the area was greatly influenced by climatic changes, some lasting one or two centuries. In turn, these changes altered the range of plants across the basin, influencing both wildlife and human use.

Archaeological research shows that people were using the area now managed by Malheur National Wildlife Refuge 9,800 years ago. At that time, the Harney Basin contained a huge lake that covered 255,000 acres. These early inhabitants used plants and animals found along the edge of this vast lake and in the surrounding uplands. Hunters used spears to hunt large game animals. Ground stone tools used to process plants, such as grass seeds and roots, have been found from this period, but are not abundant and suggest that plant foods were not as highly processed as in later periods. Abundant plant resources also meant that materials used to fashion baskets were readily available. It is around this time that twined bags, mats, burden baskets, and trays begin to appear in the archaeological record.

The climate then became progressively drier, lowering lake levels. For a while the shallower lake meant that the marsh covering Malheur Lake actually increased in size and supported more plants and wildlife. Eventually, the dry climate caused the marsh to shrink and then disappear, limiting the resources available to both people and wildlife. Evidence of Native American use of the immediate area decreases as the climate became drier and the inhabitants of the area focus their activities around higher elevation springs. Stone tools show that animals continue to be hunted in the area and there is a gradual change from the use of spears to the atlatl and dart. The atlatl consists of a piece of wood shaped with a handle on one end and a hook on the other end. It is used to hurl a light spear (dart) through the air with more accuracy than a hand-thrown spear.

Fur Trappers, Wagon Trains and Military Expeditions

“At sunset, we reached the lakes. A small ridge of land [the Harney Lake dunes] an acre in width divides the fresh water from the salt lakes. These two lakes have no intercourse. The freshwater has an unpleasant taste 1 mile wide and 9 long. This (salt) lake [Malheur Lake] discharges Sylavailles River [the Silvies River] and 2 small forks; but it has no discharge. Salt Lake at the south end is 3 miles wide. Its length at present is unknown to us but appears to be a large body of saltish water. All hands gave it a trial but none could drink it. All the country is low and bare of wood except wormwood and brush. We had trouble finding wood to cook supper. The trappers did not see a vestige of beaver. Great stress was laid on the expedition visiting this quarter. Here we are now all ignorant of the country, traps in camp, provisions scarce prospects gloomy. Buffalo has been here and heads are to be seen. Fowl in abundance but very shy.” ~ Peter Skene Ogden 1826

In 1826 French-Canadian fur trapper Peter Skene Ogden led a large expedition of trappers from the Hudson Bay Company into the Harney Basin. The fur trappers were looking for beaver, river otters, and other fur-bearing animals in rivers and wetlands in the Basin. Ogden and his company of trappers remained on the north side of Malheur, Mud, and Harney Lakes. However, had they gone to the south side of Malheur Lake, they would have found fresh water at the spring near today’s Refuge headquarters and the abundant plant and animal resources of the Blitzen Valley.

During their late fall arrival, they encountered Paiute Indians camped along the shore of the lakes. The Hudson Bay Company frequently expected local tribes to supply food for their large expedition groups. Unfortunately, the Paiutes were entering winter after a very unproductive summer and were unable to help the explorers with food. On November 3rd Ogden documents his company’s hardships and provides a description of the Paiutes and their small villages. He also describes the hardships the Indians were enduring because of a lack of food:

“From 4 a.m. snow has fallen. This will make it difficult for my 2 express men from Ft. Vancouver to find our tracks though every precaution was taken making marks at different camps; if only the Indians do not destroy these marks. It is incredible the number of Indians in this quarter. We cannot go 10 yards, without finding them. Huts generally of grass of a size to hold 6 or 8 persons. No Indian nation is so numerous as these in all of North America. I include both Upper and Lower Snakes....They lead a most wandering life. An old woman camped with us the other night and the information I have found most correct. From the severe weather last year, her people were reduced for want of food...Unfortunate creatures what privations you are doomed to endure; what an example for us at present reduced to one meal a day, how loudly and grievously we complain; when I consider the Snake's sufferings compared to our own! Many a day they pass without food and without a murmur. Had they arms and ammunition they might resort to buffalo; but without this region the war tribes would soon destroy them. This country is bare of beaver to enable them to procure arms. Indian traders cannot afford to supply them for free. Before this happens a wonderful change must happen. One of Mr. McKay’s parties was sent back to request us to raise camp and follow his tracks. A chain of lakes [most likely the springs in the Double-O area] was all they had seen, no game. Truly, gloomy are our prospects.”

Prospects did not improve for the company and Ogden recounts on November 4th: “Raised camp taking the west course and soon reached the end of Salt Lake [Malheur lake] not near so long as I expected, in some parts nearly 5 miles wide and deep, its borders flat and sandy. In the evening we camped near three small lakes [east side of Malheur Lake ]. Swans numerous. Tho’ 100 shots fired, not one killed. Nothing but wormwood this day. Salt (?) Lake maybe 10 miles in length. Mr. McKay and the party arrived with the following accounts – no beaver, same-level country a chain of lakes of fresh water. This adds to the general gloom prevailing in camp, with all in a starving condition, so that plots are forming (among) the Freemen to separate. Should we not find animals our horses will fall to the kettle. I am at a loss how to act.”

On November 5th a decision is made to abandon trapping in the area and proceed westward: “Bad as prospects were yesterday they are worse today. It snowed all night and day. If this snow does not disappear our express men will never reach us. I hope they will not fall prey to the Snakes. I intend to take the nearest route I can discover to the Clammiitte [Klamath] Country. My provisions are fast decreasing. The hunters are discouraged. Day after day from morning to night in quest of animals; but not one track do they see.”

The lack of available food and a scarcity of fur-bearing animals around the lakes led Ogden to write the name “Malheur” the French word misfortune on his maps of the area. From that time on the area would be identified as Malheur Lake. Ogden mistakenly believed the lake was connected with the Malheur River, thus providing the river with its name. It would be nearly 20 years before the next significant presence of Euro-Americans in the Basin.

Settling the Land

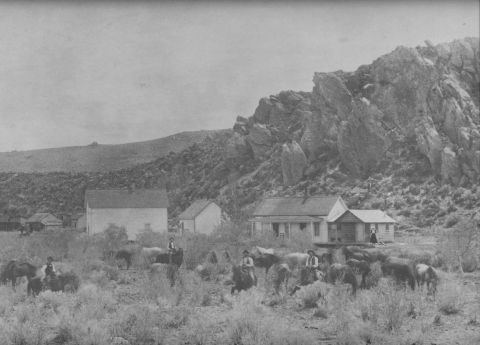

It took ten years after the passage of the Homestead Act for settlers to arrive in the Blitzen Valley. Dr. Hugh Glenn of California took advantage of the 1862 Act to begin building a vast cattle empire in Southeastern Oregon. In 1872 he sent Peter French with 1200 head of cattle, six vaqueros, and a cook to Oregon. French used the Act to claim 160 acres at the south end of the Blitzen Valley for his boss. Using this as headquarters for the ranch he managed for Glenn, French continued to acquire land over the next 25 years using not only the Homestead Act but also the Swamp Land and Desert Acts. French eventually managed a ranch that encompassed over 140,000 acres including the Blitzen, Diamond, and Catlow Valleys.

Under each of the Acts, applicants were required to make “improvements” to the land for agricultural purposes; this could include improvements for livestock grazing. As a result of these stipulations the Blitzen Valley and surrounding areas underwent a transformation from the more natural conditions attributed to pre-European contact to the highly altered landscape of today. Roads were constructed; water was directed into ditches to drain or irrigate areas; streams were impounded to control the direction and velocity of flow; meadows were hayed; and uplands were grazed.

After French’s death in 1897, the ranch was managed as the French-Glenn Livestock Company until debts forced the sale of land in 1907 to Henry L. Corbett and C.E.S. Wood of Portland. They formed the Blitzen Valley Land Company under the management of area rancher William Hanley. The goal of the company was to return the property to a successful working ranch. To accomplish this, the company needed to improve water distribution in the valley. Between 1907 and 1913 the company channelized 17 ½ miles of the Donner und Blitzen River to improve drainage of adjacent wetlands. They also authorized the construction of eight miles of the Busse Ditch and four miles of the Stubblefield Ditch to improve the distribution of water in the north end of the valley.

In 1916 the company was reorganized as the Eastern Oregon Livestock Company (EOLC). Louis Swift of the Swift Packing Company of Chicago purchased 46 percent of the company under this reorganization. The construction of a Union Pacific rail line from Ontario to Crane in 1916 made shipping livestock to market easier. Swift was interested in the thousands of feral pigs in the Blitzen Valley, as well as the cattle raised on the ranch. Under his direction, the pigs were rounded up and herded to Crane where they were loaded on stock cars and transported to his Chicago meat packing plant.

In 1920 the company established the Blitzen River Reclamation District. Tracts of 160 acres were laid out and leased in a sharecropping arrangement. Several dairies were established on these tracts and the EOLC used the railroad at Crane as a venue for shipping dairy products out of the county. The EOLC also established a hotel and store at Frenchglen in the mid-1920s. In 1918 an irrigation ditch was constructed from Page Springs along the west side of the valley to what is now known as Krumbo Lane. In 1928 Swift bought out Corbett’s controlling shares in the company and owned the ranch until 1935 when he sold it to the U.S. Government.

Setting Aside Land for Wildlife

This is historic ground for the bird man. In the early seventies the well-known ornithologist, the late Captain Charles Bendire, was stationed at Camp Harney on the southern slope of the Blue Mountains, straight across the valley from where we stood. He gave us the first account of the bird life in this region. He saw the wonderful sights of the nesting multitudes. He told of the colonies of white herons [great egrets] that lived in the willows along the lower Silvies River. ~ William Finley, Trail of the Plume-Hunter

In the late 1880’s, plume hunters were decimating North American bird populations in the name of fashion. The hunters were collecting breeding feathers for the hat industry, where the latest fad included wearing part or all of a bird on ladies hats. Shorebirds and colonial nesting birds suffered the most as hunters targeted large flocks, injuring birds indiscriminately and orphaning chicks. In an era when an ounce of breeding feathers was worth more than an ounce of gold, it’s not surprising that plume hunters sought to make a fortune by hunting birds on Malheur Lake.

On a trip to Harney County in 1908 to photograph nesting white herons (later renamed great egrets) on Malheur Lake wildlife photographers William L. Finley and Herman T. Bohlman learned that most of the white herons had been killed in 1898 by plume hunters. After ten years the white heron population still had not recovered.

In a 1910 Atlantic Monthly article entitled “The Trail of the Plume-Hunter”, William Finley provides a vivid description of their time on Malheur Lake:

1908 - Our longing to visit the Malheur country had at last been gratified...Here we were standing on the high headland looking out over the land of our quest. Here spread at our feet was a domain for wildfowl unsurpassed in the United States.

The following day we found the biggest colony of gulls and white pelicans I have ever seen. It was the sight of a lifetime. As we approached, out came a small delegation to meet us. When we got up to the colony, the whole city turned out in our honor. I have seen big bird colonies before, but never one like this. I was so excited I tripped over one of the oars and fell overboard with three plate holders [photographic plates for a large format camera] in my hand.

After hunting for seven days we returned to camp for more provisions and set out to visit another part of the lake. This time we stayed out for nine days, and saw – two white herons! At the time we thought these must be part of a group that nested somewhere about the lake; yet more likely they were a single stray bird that came our way twice. I am satisfied that of the thousands of white herons formerly nesting on Malheur, not a single pair of birds is left.

Outraged by their observations, they presented the situation to fellow members of the Oregon Audubon Society. Facing similar circumstances at Klamath Marsh, the Society pushed for the designation of both areas as wildlife refuges. As President of the Society, Finley approached President Theodore Roosevelt with the proposal. Already familiar with Finley and Bohlman because of their involvement in the establishment of Three Arch Rocks Refuge in 1907 on the Oregon Coast, Roosevelt was amenable to Finley’s proposal.

The Lake Malheur Reservation was established on August 18, 1908, by executive order of President Theodore Roosevelt. Roosevelt set aside unclaimed government lands encompassed by Malheur, Mud, and Harney Lakes “as a preserve and breeding ground for native birds.” The newly established “Lake Malheur Reservation” was the 19th of 51 wildlife refuges created by Roosevelt during his tenure as president. At the time, Malheur was the third refuge in Oregon and one of only six refuges west of the Mississippi.

Civilian Conservation Corps

The Great Depression greatly impacted the country with economic turmoil and rampant unemployment throughout the nation. In an effort to revive America, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt in 1933 created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). This action would ultimately have a profound effect on the Refuge.

Roosevelt’s plan was to recruit thousands of unemployed young men, enroll them in a peacetime army, and send them to do battle (or to wage war) against the destruction and erosion of our natural resources. This young, inexperienced $30-a-month labor force met and exceeded all expectations. Enrollee families received $25.00 off the enrollee’s monthly wage. The economic boost provided by this money was felt in cities and towns all across the nation. Between 1933 and 1942 three million young men worked on CCC projects across the United States; more than 1000 young men would complete projects during this time at Malheur National Wildlife Refuge.

With the purchase of the Blitzen Valley portion of the Eastern Oregon Land and Livestock Company holdings, the Refuge became an ideal location for CCC projects and would host three CCC camps. A seasonal camp was built near today’s Refuge headquarters during the spring and summer of 1935. The first permanent camp was established at Buena Vista Station in October 1935. Large camps were located at Refuge headquarters, Buena Vista Station and at Five Mile Lane, north of Frenchglen. A small side camp was set up at Ewing Springs on Malheur National Forest to cut timbers for work projects on the Refuge. The last camp was closed in 1942 with the start of World War II. Little evidence remains of the camps, as the wood buildings associated with the camps were dismantled by the army and moved to Alaska to serve as barracks during construction of the Alaskan Highway.

An excellent description of the construction of the permanent camp at Refuge headquarters comes from the May-June 1936 Camp Sod House Narrative:

“Sod House Camp was established here on May 5, 1936, having been moved from Cottonwood Camp in Idaho.

Approximately 121 boys are in camp for duty. The picture shows the mess hall, most of the boys’ quarters, and officer’s quarters, is shown, with the Blitzen River in the right foreground. Malheur Lake is beyond the trees in the left foreground and next to the low hills in the distance.

The site is the place where one of the earliest buildings stood adjacent to Malheur Lake, a sod house built by two brothers, Chapman, and from this place came to be called Sod House Spring. The site for the headquarters was selected because it is centrally located, geographically, with respect to the lands of the refuge, accessible, both from the lands of the original refuge bordering the lake and the recently added sixty-five thousand acres of the Blitzen Valley which extends thirty-five miles south from the shores of the lake.

The site of the buildings is on the north slope of a low hill giving a fine view of the lake to the north and an abundant supply of water is furnished by Sod House Spring.”