On a warm October morning along Colorado’s front range, late autumn winds ushered sighs of cool relief and sounds of celebration to Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuge. To most Indigenous people, the wind represents change.

This year (2021) was the first time Indigenous peoples joined refuge staff for the roundup of bison.

The people gathered and prayed in a small group representing Arapaho, Ute, Nakota, Lakota, Dineh, Comanche, Hopi, Apache, Mexihca-Aztec Nations and Europeans to be with the bison.

According to Beverly Castaneda, Americas for Conservation, who was pivotal in organizing the gathering at Rocky Mountain Arsenal, “It is believed that the bison gather to give the people their medicine in a prayerful way. The bison is one of the sacred animals and brought the people to stand united for Mother Earth and to help her get restored. Through unity and utility amongst the people and these powerful beings, we will be able to restore and heal the land in balance so the land can heal, so we can heal before it is too late and run out of time.”

In another first, this year’s bison are being donated to the Sicangu Lakota Oyate — or Rosebud Sioux Tribe — and their Wolakota Buffalo Range.

From the refuge just outside of metro Denver to remote lands of the Nation in South Dakota, the over 400-mile journey is a step forward in conserving this iconic species while preserving Native American cultures tied to its very existence.

Beverly continued to add: “As we stand together, the Bison bring messages. The Bison say we must learn to work together in harmony and unity.” She then prayed: “Creator, it is the mother lands that needs healing and restoration for all life. When we heal the lands, she will heal the peoples. Creator, when we work together, we are stronger. Putting difference aside to work on what is important to for all humanity is Mother Earth. When we learn how to do this together, we will then have the medicine for the next generation to come.”

Buffalo People

No matter your background, chances are that looking into the eyes of this animal evokes strong emotion. At once, the American bison is a symbol of medicine, sustenance, sacrifice, heritage, and hope.

Dating back far beyond our collective memory, these majestic animals have been considered the sacred Brother Buffalo. With their chestnut-brown fur, curved horns, and powerful muscles, bison are a hallowed animal for many Indigenous people. For thousands of years, Native Americans relied heavily on bison for their survival and well-being, using every part of the bison for food, clothing, shelter, tools, and jewelry, and in ceremonies.

“Everything was made from that animal. The buffalo stomach is a container you would use to hold water; put hot rocks in, and it would boil. The hooves, you’d boil down to make glue. Needles, awls, the thread from sinew. The bladder was a water pouch. Horns for cups and combs. Shields made from the neck of a buffalo were an inch thick; they were said to ricochet bullets.” — Jason Baldes, Eastern Shoshone, told Bitterroot Magazine.

This Symbol of the North American Prairie was Nearly Lost

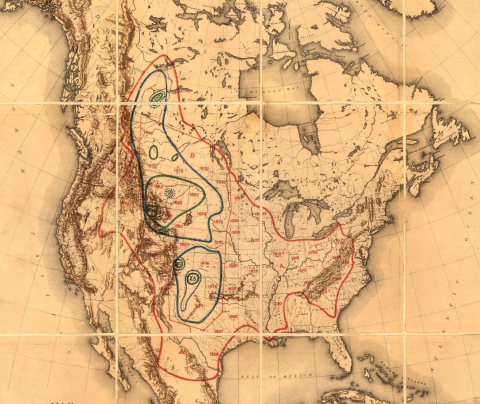

Upward of 30 million bison once ranged from Alaska to Mexico, extending eastward to New York and Georgia. For comparison, today some of the only species that can be found across such a large swath of North America are the common house mouse, white-tailed deer, and American robin.

In the 1800s, bison began a dramatic decline due, in short, to habitat loss and increased hunting pressures. It’s estimated their population crashed to only 500–1,000 bison. The decimation of millions of bison in the 1800s was pivotal both in our conservation history and in the devastation of many Tribal Nations.

“The government realized that as long as this food source was there, as long as this key cultural element was there, it would have difficulty getting Indians onto reservations,” University of Montana anthropology professor S. Neyooxet Greymorning told Indian Country Today. Soldiers alone couldn’t kill millions of buffalo, but they could facilitate extensive market and recreational bison hunts. Demand for buffalo robes and bison leather, used for mechanical belts in the early days of the industrial revolution, meant bison were driven nearly to extinction by 1884. Some northern Tribes lost their supply of bison in just a decade.”

Preserving the Spirit and Independence of Tribes Through Wildlife Conservation

Long told by Tribal elders are oral tales of a Pend d’Oreille man named Atatice who spurred some of the earliest bison conservation efforts, a legacy that was carried on by his son, Latiti.

“Atatice saw the buffalo disappearing, and he knew something needed to be done,” said Atatice’s descendent Roy Bigcrane.

The incredibly worthwhile documentary “In The Spirit of Atatice” tells the story of Atatice and Latiti, bringing their story into our collective history of bison conservation while also sharing the story and heartbreak of the Native peoples who managed bison and lands of the Flathead Reservation.

In 2021, in a move that honored and continued this legacy, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service transferred ownership of the National Bison Range back to the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. It is now known as the Bison Range and stands as a testament to the importance of intergovernmental partnerships between Tribes and agencies.

To reestablish bison populations while preserving history, culture, tradition, and spiritual relationships for Native American peoples, a group of 69 Tribes from 19 states have united under a common mission of restoring bison to Tribal lands. These strategic partnerships, known collectively as the Intertribal Buffalo Council, have led Tribes to manage approximately 20,000 bison across their native landscape.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service manages bison herds across six national wildlife refuges alongside other agencies including Bureau of Indian Affairs, Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Geological Survey, and National Park Service. It is currently estimated that 11,000 bison have been brought back to public lands in 12 states.

Together, these agencies and Tribes collaborate to strengthen their resources, institute a conservation genetics framework, and publish investigations into metapopulation management and herd health. Mutual respect and cooperative work with Tribes, states and stakeholders are essential to continue a legacy of bison conservation.

Rebuilding, Together

The roundup at Rocky Mountain Arsenal was part of a bigger effort to send bison to the Wolakota Buffalo Range. Five hundred bison from Theodore Roosevelt National Park, Fort Niobara, Wichita Mountains, and Rocky Mountain Arsenal National Wildlife Refuges will make their way to the Range this fall. After spring calves are born, the herd is expected to surpass a milestone of 1,000 bison back on the landscape. This comes only one year after the Wolakota herd was established, with just 100 animals.

“This project has been so successful because it embraces who we are as Lakota. We are buffalo people,” said Wayne Boyd, interim CEO of Rosebud Economic Development Corporation. “We hope that others learn from Wolakota and see the impact that can be achieved by bringing together public, private, and tribal partners to healing our people and land.”

Our Tribal partners remind us that we are connected to this land and the wildlife, and that it is important to take time to appreciate and honor that relationship.

During the first-of-its-kind private ceremony at Rocky Mountain Arsenal, Tribal members offered prayer and songs, burned sacred medicine to honor the bison, and left gifts in offering to the bison for their safety, and to express gratitude for calling them back to their old ways. This ceremony created a sense of harmony, peace, and understanding and was an opportunity to reflect on how we can all care for Mother Earth and the Ancestors of the land.

Having watched another chapter of bison conservation unfold during the refuge roundup activity, Education Specialist Tom Wall reflected, “Wildlife conservation is all about relationships. Hosting the Native gathering at the capture and sending bison to the Rosebud Sioux Tribe is a step in mending our relationships with Indigenous people and the wildlife we protect in our region.”

David Lucas, Project Leader of Colorado’s Front Range National Wildlife Refuge Complex and member of Interior’s Bison Conservation Initiative, explains that “without changes in our management philosophy, we’ll begin to lose the bison species over the next 200 years.”

Analysis from the Department of the Interior found that increasing genetic diversity by strategically sharing small numbers of bison between herds will effectively mitigate the negative genetic consequences of managing small herds in isolation.

David went on to add, “The good news is we can remedy this by moving animals between our herds to ensure the genetics of bison continue.”

He continued: “Bison help us with refuge goals to maintain and improve grasslands. But we also have bison because it is the right thing to do. They are an iconic prairie species who should have a place in our world. They were our nation’s first endangered species. We nearly extirpated them. Now we can work to correct that for the benefit of all the work we do to conserve the prairie and its peoples.”

Beverly Castenada’s deep connection left a lasting impression that won’t soon be forgotten. “As I walked to the Bison, my body had a response, an emotional reaction as my eyes began to tear. I am grateful to be given the space to be with the Bison’s powerful presence, that was felt throughout my body.”

Beverly added: “We must continue respecting the Bison as they are sacred living beings of this planet and we need them to prevail on her, our Mother Earth.”

Written by Jessica Sutt, Melissa Castiano, and Christina Stone, in collaboration with Beverly Castenada, Yoloteotl Chalchihuit, Aaron Epps, David Lucas, and Thomas Wall