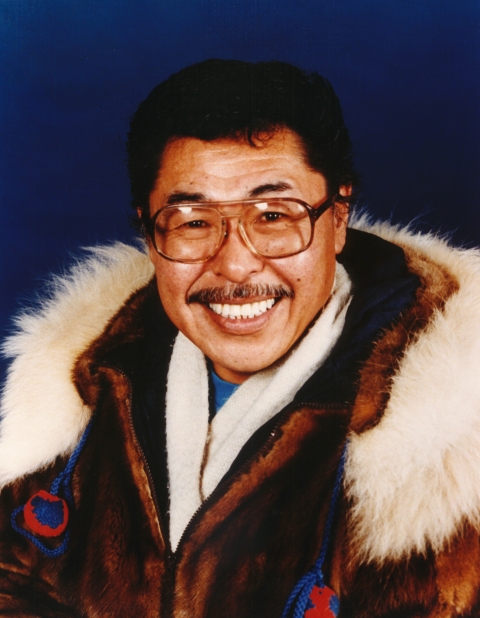

When Chris Tulik first joined the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Yukon Delta National Wildlife Refuge as a Refuge Information Technician (RIT) more than thirty years ago, populations of emperor geese returning to the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta had significantly declined to the point that some believed there was a threat of extinction. Tulik and several other RITs were hired to help reach out to local villages to spread news that harvest of the bird was closed, and to engage them in a new conservation strategy. It was a hard job that finally paid off this year when the restriction on harvest was lifted.

Tulik grew up on Nelson Island, approximately 100 miles west of Bethel, in a one-room house with no electricity, running water, or television and the only food his family had was what they gathered from the land and sea. He remembers when he first saw the RIT job announcement.

“I looked at the qualifications where it said ‘a local person with the knowledge of tradition and culture,’ I figured right away, that was my qualifications,” he said.

Tulik applied and was surprised when he got a call from a man named Chuck Hunt telling him that he was hired. Hunt, a Yup'ik man from the delta and a native liaison with the refuge, had recently helped complete the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta Goose Management Plan. People from throughout the Emperor’s flyway, who represented diverse interests, including from the more than 40 Yup'ik villages on the delta, had been engaged in the process to develop the plan. It was now time to implement that plan.

Tulik didn’t realize the difficult job that lay ahead. He would have to travel to villages to tell people they couldn’t hunt for species that they had hunted for all their lives. Many of the elderly people at the time didn’t speak or understand English. It was up to Tulik and the other RITs to explain the situation. People in the villages would see the RITs in uniform and associate them with law enforcement. They were viewed as traitors, part of an effort to destroy the native culture.

“I recall traveling to the villages in 1984 and telling the people that the [emperor goose] population had declined to a dangerous level and that they are closed to harvesting,” said Tulik. “That was a hard thing to do. It was tense.”

Not only was it hard for Tulik to deliver that message, it was hard for him to give up hunting emperor geese, too. He stayed with the Service for a couple of years and then moved on. He would later regret having left. He saw other RITs continue in their careers and advance to other positions in Service. He began to think of returning and as luck would have it, he saw an advertisement in the local paper, just as he had years ago.

Now he is the lead RIT at the refuge, coordinating three others. This spring for the first time in more than 30 years, the emperor goose season was opened. Tulik and the rest of his team went to the villages to tell the people they could once again hunt these birds.

“We told the people it’s finally open, we can go hunt and get what we need,”Tulik said. With a big grin on his face he added, “I am looking forward to having a taste of emperor goose myself.”

While the emperor goose restriction was lifted this year, restrictions on subsistence fishing over the last few years due to Chinook salmon declines have made it difficult for people to fill their winter food caches. The situation has caused some tension, but Tulik is still enjoying his job. For him, being out in the villages is not like it was 30 years ago. He describes visits to the villages as “fun.” He gets to speak Yup'ik, his native language, laugh and joke with people.

“People are welcoming us,” he said. “They are talking to us and they are finding us more helpful. Even the non-Native Fish and Wildlife employees are being welcomed in the villages.”

Looking back on how things were when he first started, Tulik described the relationship as being “impossible” and “hopeless.” Now, he said, “what was once an unpaved, bumpy road has now been paved.”

“The working relationship we now have is an accomplishment, but it must be solidified” Tulik said. “The next generation must be built into the relationship.”

Chuck Hunt, who hired Chris 30 years ago and was the inspiration for the RIT positions, cared deeply about the RITs. He even turned down a promotion, to stay at the Yukon Delta Refuge so he could continue to support and mentor them. Hunt would be proud of the difference that the RITs have made in the Service’s relationship with the Yup'ik people of the Delta.

Hunt’s legacy is not just limited to the Yukon Delta Refuge. There are now RITs working for refuges across Alaska. They live in villages on or adjacent to the refuge for which they work and know the local language and culture. The RITs teach Service employees about local customs and traditions, serve as Indigenous language translators, provide information on hunting and fishing, and lead youth education programs.

As for the future, Tulik wants to “take the RITs under his wing to build the team spirit and loyalty. The Yukon Delta Refuge has more villages and subsistence users than any other refuge in the state. We need to work together as a team.”