Editor’s note: The following article excerpts notes from a question-and-answer session with a noted Service biologist in February 2018. They’ve been reprised to help showcase Black History Month.

Perhaps there never was a time when Melvin Tobin wasn’t a conservationist. He hardly had a choice.

There was his upbringing: he, his father and mother and kid brother, all working a South Carolina farm. There, young Melvin encountered nature at every turn – in the fields that put food on their table, in the creeks where swimming creatures lurked, in the forests where a crackle in the leaves announced an animal was nearby.

“I think about the times when my brother and I would observe various wildlife species to learn more about their behavior,” Tobin recalled in a 2018 interview. “We would hunt and fish, while observing the wildlife we saw around us, which created a passion for preserving wildlife and their habitat.”

And this: A weekly regimen of “Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom,” the long-ago TV show in which an intrepid explorer probed the wild world, fueled his imagination.

(People of a certain age recall that celluloid hero, Marlin Perkins. In a career that spanned continents and decades, Perkins dared the fates in close encounters with snakes, alligators, bears and other creatures that weren’t aware that Homo sapiens were the dominant species.)

“I … loved that show,” Tobin recalled. “I didn’t know I could get a job doing that.”

Not only a job, but a calling. Tobin, 66, is a Service veteran. His 42-year career has taken him from a deer-research station in South Carolina to his current job as field supervisor at the Service’s Arkansas Ecological Services Field Office. He’s enjoyed several stops along the way.

At every point, Tobin has made it a point to promote not just conservation, but the Service itself.

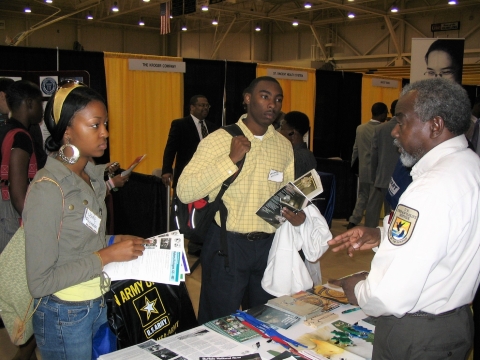

“As an employee with the FWS, I was able to make a difference at career fairs, frequently seeing some of those same students that I interacted with, working for the Service and other conservation agencies,” Tobin recalled in that interview four years ago. “I have had the privilege of seeing and observing how they have developed in their careers, establishing themselves as leaders in conservation.”

A life-changing offer

His first job was truly hands-on. After getting an undergraduate degree from Benedict College in Columbia, South Carolina, Tobin became a white-tailed deer biologist for the South Carolina Wildlife and Marine Resources Department (now South Carolina Department of Natural Resources). He worked at a field station in Bonneau, about 42 miles north of Charleston. Tobin was part of a team that raised white-tailed deer fawns to obtain known age fetuses from known age deer when they were old enough to breed. That research led to the creation of a fetal development scale that allowed the user to predict when a fawn would have been born or the month when a doe would have breed, hence determining the peak of the fawning season or the start of the breeding season.

It also led Tobin to an encounter with a man who would help change his life.

He was in Washington, D.C. visiting the Department of the Interior during the mid 1980s. There, he was introduced to Benjamin Tuggle, who would later go on to direct the Service’s Southwest Region. Tuggle made the young biologist an offer that was too good to pass up: How would Tobin like to get a master’s degree in wildlife at Louisiana Tech University as part of Grambling State University.

The Louisiana university, Tuggle continued, was the home of the Grambling Cooperative Wildlife Project. The young biologist could do graduate work there; Tuggle, the co-op’s leader, would be his boss and mentor.

“I accepted his offer and became the first and only student to acquire a master’s degree through the program,” Tobin said.

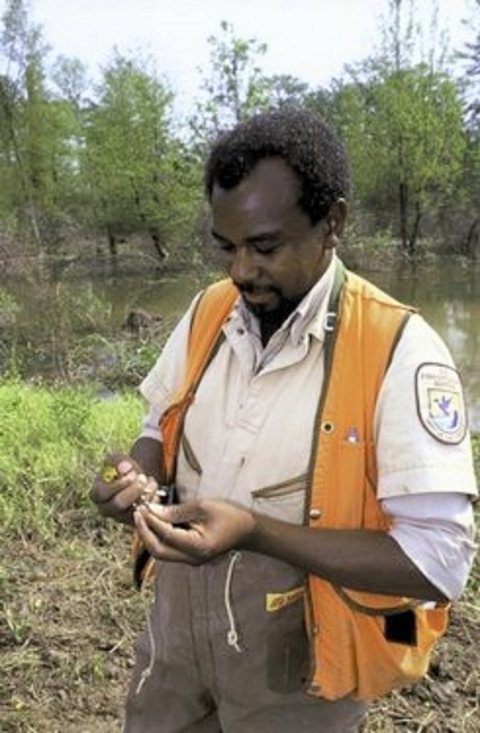

Upon graduation, the newly minted graduate in 1990 started his first job with the Service as a private lands fish and wildlife biologist at the Tensas River National Wildlife Refuge. For Tobin, his new job was something of a homecoming. While a graduate student, he interned at the northeast Louisiana refuge.

Those were good years. He worked as a private-lands biologist, wrote the first draft wildlife inventory plan for the refuge and was responsible for numerous wildlife surveys and Farmers Home Administration tracts administrated by the refuge.

In 1996, he accepted a position in Ecological Services and moved to Arkansas. Tobin became the first official employee for the Arkansas ES Field Office. He became the state coordinator for the Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program in Arkansas, later becoming a team leader for that office.

As team leader, Tobin was a juggler. He still oversaw the Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program, while simultaneously supervising the office’s endangered species program. He also headed its information technology, coordinated Service work with the USDA Farm Bill, and worked with biologists on karst (a type of landscape where the underlying rock formations are partially eroded by water; caves are notable examples) and cave-related issues.

These days, Tobin leads an office that has grown to 12 people. He supervises a deputy field supervisor, the staff, Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program, and two sub-offices located at the Cache River NWR and the Ozark St. Francis National Forest Service in Arkansas.

Let’s not forget the landscape level projects and lives he’s touched.

‘A lot of time’

People driving through the Lower Mississippi River Valley may not notice the bottomland forests, nor the wetlands, as they zip along. Those landforms are tangible proof that conservation works. Tobin knows.

For more than 25 years, Tobin has worked with an array of partners – the Natural Resources Conservation Service, The Nature Conservancy, Ducks Unlimited Inc., private landowners, federal and state wildlife agencies, and many others – to restore bottomland hardwoods and wetlands. Those efforts, along with others, have encompassed over 700,000 acres in Arkansas, Louisiana and Mississippi, most of those tracts in private hands.

Restoring these lands, Tobin said, was important for migratory waterfowl, neotropical migratory birds, shorebirds, and marsh and wading birds which need forests and wetlands for habitat and foraging.

“It took a lot of time and work to get landowners to see the vision and get them on board for the enhancement of conservation for these species,” he said.

In time, they shared that vision – and the cheers. In October 2017, the Service, its partners and landowners gathered in Louisiana to celebrate their efforts with the 700,000 Acre Celebration. Tobin called it “an important point” in his career.

There were others. He put into effect the draft Wildlife Inventory Plan at the Tensas River NWR. Tobin paid close attention to hiring at the Arkansas ES Field Office.

And he’s touched lives.

Ron Hollis knows. In 2003, he was a teacher at a private christian school in Little Rock, Arkansas. He also was worried: the school was losing funding for high school teachers. Tobin – by then, he had added “Service recruiter” to his various duties – suggested Hollis get acquainted with the Service through its Student Career Experience Program. Hollis said yes, and took a summer position that year at the White River NWR.

Today, Hollis is the refuge manager at Canaan Valley National Wildlife Refuge in West Virginia.

“Melvin has always been a person that I could reach out to and ask advice on next steps for me in my career,” Hollis said. “No matter how much time had passed it seemed as if we just talked days ago. He always let you know that he had been watching your career over the years and encouraged you to do better.”

Tobin believes his work with younger people was “life changing” for him.

“I get a chance to talk to other students and for some have been instrumental in making a difference in their lives,” he said in 2018. “For several students, I was able to introduce them to conservation and the FWS, where some are employed today.”

“As an employee with the FWS, I was able to make a difference at career fairs, frequently seeing some of those same students that I interacted with, working for the Service and other conservation agencies,” he said. “I have had the privilege of seeing and observing how they have developed in their careers, establishing themselves as leaders in conservation.”

Now, in the latter years of his tenure in the Service, Tobin looks at the lives he’s touched – and knows that he, too, has been touched. Helping others does that.

“As I reflect, I am reminded of how I was able to bring people … into (the Service) and see them grow throughout their careers…” he said. “(S)eeing what they have become is a life changing experience for me.”

Maybe he turned a few of them on to a long-ago TV show, too.