Since time immemorial, Indigenous peoples have used fire as a land management tool, shaping the land as we know it. But when European settlers arrived, they adopted a fire- exclusion approach and prevented the use of traditional fire practices. Today, we are grappling with the consequences of those actions.

Wildfires naturally occur, but changes to fire management practices — including the prevention of traditional practices, coupled with hotter, drier, and longer fire seasons due to climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change — cause increased fuel buildup and create environmental conditions for more frequent and intense fires.

These changes add challenges to wildfire management and endanger human lives, communities, infrastructure, and the natural resources we depend on. Tribal communities, with their close connection to the land, are disproportionately impacted.

Restoring balance in this complex ecosystem is difficult and requires all our resources and dedication. For this reason, wildfire managers are learning from Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge — the knowledge acquired by Indigenous peoples through many generations of direct contact with the environment in a particular place — in the ongoing efforts to develop a solution. Addressing these impacts compels the Service and our many partners, including Tribes, to work toward a collaborative conservation model of landscape and wildland fire management.

The Important Role of Wildfires

Fire is a vital conservation tool. Roughly 80% of Service-managed lands, from marsh to forest to prairie, evolved with fire and depend on periodic burns to remain productive wildlife habitats.

On fire-adapted landscapes with frequent natural wildfires, less severe fires naturally “clean” the forest. These less-severe fires decrease diseases and invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

Learn more about invasive species , provide more food for wildlife from the fresh growth, and remove flammable and thick vegetation to allow more sunlight and support a diversity of life. They also enrich the soil from the ashes of plants, fallen leaves, pine needles, and small woody debris.

While wildfires can be a tool for regeneration, extreme fires fueled by climate change can be devastating for species, habitats, and surrounding communities. By working with multiple stakeholders, including Tribes, we are more equipped to address the impacts of severe wildfires.

Learning from Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge

For generations, Indigenous peoples have been living in harmony with fire-adapted-and-dependent lands through applying Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge landscape management practices. These traditional practices vary across Indigenous communities.

More than just decreasing the threat of catastrophic wildfire and supporting resilient lands, controlled, less-severe fires often promote the growth of culturally significant resources. Fresh shoots from willow and bear grass for basketry material and new plant growth to support deer and elk populations are two examples.

Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge is particularly important for identifying environmental changes attributable to climate change at the local and regional level. Understanding traditional practices and the potential impacts of climate change on land, wildlife, and subsistence users is critical during federal decision-making processes. Applying an Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge lens informs conservation of species and habitats, provides a comprehensive approach for climate change projects, and shapes the ways the Service collaboratively manages fire on while reducing the risk of damage to surrounding communities.

Finding Solutions through Collaborative Management

Three locations across the country provide a model for the ways in which the Service, Tribes, and our many partners are working together to address the impact of climate change and wildfire:

Alaska

While wildfire varies from year to year, Alaska’s fire season is becoming hotter and longer, creating environmental conditions for more frequent and intense fires. Over the past 30 years, Yukon Flats — the traditional homeland of the Gwich’in and Koyukon Athabascan people in eastern interior Alaska — has experienced a clear shift toward more frequent, larger fire seasons. Since 1988, the frequency of years that burned over 250,000 acres on Yukon Flats has quadrupled.

That’s of particular concern for Alaska Native peoples who follow traditional subsistence ways of life, given that access to certain species can be a matter of life and death. The smoke risk is also a health concern for remote villages, where access to health care is limited, and hospitals and clinics are difficult to access.

“With ecological transitions happening so rapidly, it’s not practical to plan for a steady-state refuge,” says Jimmy Fox, Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge manager. “We have to plan for the future refuge – one that may have a different suite of species assemblages and wildfire regimes.”

Back in 2020, the Service and the Alaska Conservation Foundation (ACF) signed a five-year cooperative agreement to enhance collaborative conservation by leveraging resources among the Service and its many partners through the Northern Latitudes Partnerships (NLP). Since then, Alaska Native Tribes, Alaska Native organizations, the Alaska Department of Fish and Game, and the Service have worked together to design six high-priority projects.

One of these high-priority projects invited scientists, Tribal members, and Alaska Native organizations to discuss climate change impacts from current and projected wildfire dynamics, carbon emissions, and permafrost melting. With the help of the Alaska Fire Science Consortium, the project continues to help ongoing conversations with Tribes and inform wildfire management in and around Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge.

Oregon

For years, the Service and partners have worked to mitigate climate change and the risk of extreme fire in southwest Oregon. Lomakatsi Restoration Project is a primary partner in this region. For nearly three decades, the nonprofit has focused on creating social equity and economic opportunities, while working collaboratively to enhance wildlife habitat and reduce wildfire risk.

A prescribed burn is the controlled use of fire to restore wildlife habitat, reduce wildfire risk, or achieve other habitat management goals. We have been using prescribed burn techniques to improve species habitat since the 1930s.

Learn more about prescribed burn on the top of Lower Table Rock in Medford, Oregon. Photo by BLM | Image Details

“By working closely with community-based nonprofit organizations like Lomakatsi, we’re able to leverage Service resources and expertise into projects that meet the diverse needs of local communities and jurisdictions, while promoting ecocultural values,” says CalLee Davenport, acting regional coordinator for the Service’s Partners for Fish and Wildlife program. “With an all-lands restoration approach, we maximize the benefits to wildlife habitat and reduce the risk of wildfire on a landscape scale.”

Lomakatsi champions Tribal members as the first, best stewards of the land.

“We are still here is the regional Tribal motto,” says Belinda Brown, Lomakatsi Tribal partnerships director. "Involving Aboriginal people in collaborative, landscape-scale restoration projects brings a wealth of place-based knowledge and promotes ecocultural values that are essential to Tribal communities”

Through their Tribally led Tribal Partnerships Program, Lomakatsi assists Native partners in building their capacity through workforce development, training programs, and fostering Tribal businesses, layered into landscape-scale restoration projects.

Two projects exemplify these Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge informed collaborative efforts on wildfire:

- Initiated in 2015, the Table Rocks Oak Climate Adaptation Project aims to reduce community wildfire risk and restore critical oak habitat at a regionally iconic and important cultural site in the Rogue Valley, while returning beneficial fire to the land.

- Since 2010, the Ashland Forest Resiliency Project has become recognized as a national model for ecological community wildfire protection, treating 13,000 acres with ecological thinning and prescribed fire. “By working closely with partners such as the Service across federal, city, and private lands, the Ashland Forest Resiliency Project is reducing the risk of severe wildfire in a changing climate and helping to protect wildlife, communities, and drinking water,” says Marko Bey, executive director of Lomakatsi.

Arizona

The Service’s Southwest Region focuses on strong and holistic ecological restoration initiatives with support from Tribal partnerships and Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge – all of which is increasingly necessary as fire seasons lengthen and fire intensity heightens. Two such restoration projects, one nearing completion and another in its introductory stages, are:

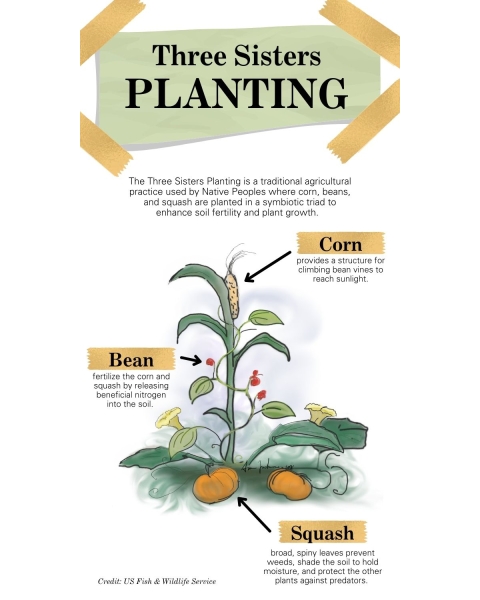

- On Buenos Aires Wildlife Refuge in Arizona, the Cumero Burned Area Rehabilitation Project successfully planted close to 13,000 plant, bush, and tree species following the 4,000-acre Cumero Fire in July 2018. The restoration approach is inspired by the traditional Three Sisters Planting practice, a method used by Native people for thousands of years for their agricultural needs. The ongoing project successfully planted species in triads – corn, beans, and squash – to enhance soil fertility and plant growth.

- Along the Gila River drainage south of Phoenix, a second Burned Area Rehabilitation Project is helping restore vital habitat. Threatened and endangered species, including the yellow billed cuckoo, Yuma ridgeway’s rail, and willow flycatcher, use this vastly ecologically important habitat damaged by the Avondale Fire in June 2020. The site has also been utilized by Native peoples for generations. As part of a larger restoration cooperative through the Rio Reimagined group, this rehabilitation project combines a coalition of organizations consisting of federal agencies, state, and local governments and consults with Tribes on cultural resource impacts.

Building Wildfire Resilience in Our Communities

Collaborative conservation management invites all of us to take part. Roughly 80% of wildfires in the United States are ignited by humans. These preventable wildfires threaten lives, property and precious natural resources.

Find out if you live in a wildfire-risk zone and follow safety recommendations on Firewise. In your community, address wildlife habitat loss by planting vegetation that provides food and shelter for birds and insects. Also, participating in your community's urban planning can help encourage responsible building practices in environments near fire-prone ecosystems.

All together, we can improve collaborative landscape management by applying Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge aimed at achieving conservation objectives and honoring socio-cultural values. Through listening and learning more about Indigenous Traditional Ecological Knowledge and the science behind landscape management, we can continue to collectively improve wildfire resilience and forest health while protecting our ecosystems and communities in the face of climate change.

- This article is from the spring 2022 issue of Fish & Wildlife News, our quarterly magazine.

- More Fish and Wildlife News.