After 20 years of work, the Chesapeake Bay can finally bid goodbye and good riddance to the exotic, invasive nutria — who for years has wreaked havoc on marsh landscapes.

On Friday, September 16, the Chesapeake Bay Nutria Eradication Project invited leadership from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, state and federal leaders, and local partners to celebrate the long-earned eradication of the rodent and tour the Chesapeake Bay marshes to learn more about the removal efforts.

Nutria and their destructive feeding habits have destroyed thousands of acres of marshes since the 1940s when they were introduced to the Delmarva peninsula in Maryland from South America for the fur market.

Maryland’s Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge has seen some of the worst of this destruction and has lost over 5,000 acres of wetlands due to the combined siege of nutria impacts, sea-level rise, and land subsidence.

In 2004, the total annual economic, environmental, and social services losses due to nutria damage were estimated at $5.8 million with projections to drastically increase if nutria were not addressed.

In order to address the problem, we along with U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Wildlife Services, and Maryland Department of Natural Resources formed the CBNEP, which worked closely with private landowners and other public partners.

Half of the 14,000 nutria removed during the project were from private lands, thanks to over 700 participating landowners, which ultimately protected over 250,000 acres of marshes on the Delmarva Peninsula.

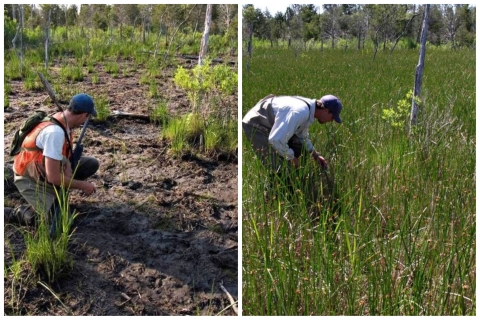

To detect and remove the rodents, the CBNEP deployed specialized detector dogs, who were trained to detect scat. The dogs and their handlers were key to confirm the absence of nutria in previously trapped areas.

“Traditional tools, such as trapping and wildlife surveys, were integrated by wildlife biologists with new technology and detector dogs. These tools were applied by dedicated individuals to put every nutria at risk, every day of the year. Due to this hard work, partnership, and perseverance, we are excited to announce the destructive invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

Learn more about invasive species , nutria, will no longer be damaging and destroying the marshes of Delmarva,” said Kevin Sullivan, USDA-Wildlife Services State Director.

The project was the first of its kind — attempting to eradicate an aquatic mammal from a non-island locale. The group has worked for 20 years to fully eradicate nutria from the region.

In 2015, the project hit an inflection point, when the last known Maryland nutria was captured.

Since then, CBNEP has been monitoring and revisiting historic nutria areas to ensure eradication through statistical monitoring. The team has moved into a scaled-down biosecurity phase to respond to any reported sightings and assist other states like Virginia that are experiencing an increase in nutria that could potentially reinvade the Delmarva if not controlled.

The removal of nutria reinforces other ongoing efforts to bolster marsh resilience in the Chesapeake, where sea level rise and historic ditching and diking efforts of the past are quickly converting acres of marsh into open water. Managers have also been placing native plants, depositing thin-layer sediment, and restoring hydrology to help rebuild marsh processes that will help the landscape keep up with climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change . These resiliency efforts would not be possible if nutria remained on the Delmarva Peninsula.

The project was funded by the National Wildlife Refuge System and Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program, and supported by 27 partner organizations. The Service’s Chesapeake Bay Field Office and Chesapeake Bay Marshlands National Wildlife Refuge Complex administered the project, implemented by a crew of 17 federal wildlife specialists from the Department of Agriculture’s APHIS Wildlife Services.

“After years of hard work and partnership, we have proven that eradication of this invasive species is possible,” said Maryland DNR Secretary Jeannie Haddaway-Riccio. "Maryland’s wetlands, particularly in this region, are special because of their ecological and economic importance but also because of their historic and cultural significance, and we have successfully protected them from this threat.”

“The Chesapeake Bay Nutria Eradication Project is an excellent example of foresight and collaboration,” said Service Director Martha Williams. “This project is a powerful case study for how federal and state agencies can work closely together to achieve a shared goal that benefits the environment and the community.”