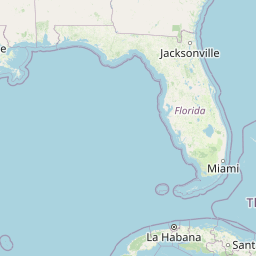

Location

States

FloridaEcosystem

Forest, Urban, WetlandIntroduction

Southern Florida encompasses a vast landscape that includes but is not limited to the Miami metropolitan area, the Florida Keys, and Everglades National Park (ENP), the largest tropical wilderness in the U.S. This region comprises a unique network of wetlands, marshes, and swamps often surrounded by urban development. With its wilderness habitat and a subtropical climate, Florida is one of the most biologically rich states in the country.

From 1975 to 2018, individuals participating in the live pet trade brought over 180,000 Burmese pythons (Python molurus bivittatus), a constricting snake native to southeast Asia, to the United States. Burmese pythons became established in the area by the 1980s due to releases and escapes (Wilson et al. 2011). Since their introduction, Burmese pythons have disrupted the ecosystem by contributing to drastic declines in native species (95% decrease in observations of some mammal species after pythons became established from 1996-2016 in ENP; Dorcas et al. 2012). Burmese pythons can appear in public spaces, but are not venomous and the risk to human safety is extremely low (Reed and Snow 2014).

In 2012, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed Burmese pythons as injurious under the Lacey Act which prohibited importation of the species into the U.S. or transportation across state lines without a permit. Until recently, the pythons were regulated as a Conditional Species in Florida, which limits their possession. In April of 2021, new rules changed their listing from Conditional to Prohibited, further limiting their possession in Florida. Additionally in 2021, 15 federal, state, and local agencies, along with tribes, and a non-governmental organization completed the Florida Python Control Plan (FPCP) which addresses the need for a unified, interorganizational plan for the control of invasive Burmese pythons.

Key Issues Addressed

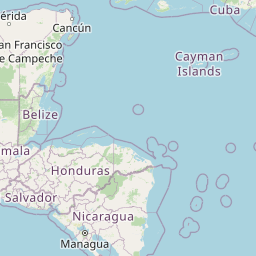

Burmese pythons’ generalist diet, semi-aquatic behavior, and cryptic nature make them highly successful invasive predators. They are natural swimmers with a prolonged tolerance for saltwater, making southern Florida suitable habitat. This species can grow up to 20 feet long, live over 25 years, and females can produce clutch sizes of up to 100 eggs per year. Burmese pythons do not have many natural predators in southern Florida, providing the opportunity for rapid population growth. Additionally, Burmese pythons can travel up to 48 miles in a few months and are capable of homing, or returning to specific locations, after relocation.

Burmese pythons have negatively impacted native species in southern Florida. They are known to directly prey on mammals, including the once-abundant marsh rabbit (Sylvilagus palustris), birds, such as the federally endangered wood stork (Mycteria americana), and even reptiles, including American alligators (Alligator mississippiensis). They may also compete with native predators, such as the threatened indigo snake (Drymarchon couperi), by reducing available prey. Additionally, Burmese pythons carry a non-native lung parasite (Raillietiella orientalis) from Asia that now infects native snakes. For these reasons, it is crucial to control Burmese python populations in southern Florida.

Controlling Burmese python populations requires active removal efforts by multiple agencies and organizations. Educating snake owners, enforcing rules and regulations, and providing alternative release options are critical to slowing the introduction of Burmese pythons and other non-native species. Eliminating pythons already present in southern Florida is challenging because the snakes are exceptionally cryptic, making them difficult to detect and remove, with the probability of detecting a python being less than 1% (Nafus et al. 2020). Partners use multiple techniques to control Burmese pythons and the State of Florida encourages the public to get involved if they are willing and able to humanely kill pythons. Further research is needed to find more efficient means of detection.

Project Goals

- Implement and evaluate the effectiveness of innovative tools and techniques to improve detection and removal of Burmese pythons in southern Florida

- Coordinate with partners to control Burmese python populations throughout southern Florida

- Prevent the spread of Burmese pythons and other invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

Learn more about invasive species by increasing awareness about their impacts to the ecosystem

Project Highlights

Florida Python Challenge®: This Burmese python removal competition raises awareness of their negative impacts and engages the public in conservation efforts. In 2021, competitors removed 223 pythons during the Challenge!

- eDNA: Researchers are using environmental DNA (eDNA), DNA released from an organism into the environment, to detect pythons without visually observing them. eDNA can confirm python presence or absence and researchers can compare findings to visual survey results in the same areas.

- Python Detection Dogs: The Auburn University EcoDogs program conducted a study to determine if dogs could successfully locate pythons in ENP. Results showed that dogs had slightly higher detection rates compared to human search teams in controlled areas. More recently the Miccosukee Tribe, Crocodile Lake National Wildlife Refuge, and the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) have implemented Python Detector Dog teams.

- Radio Telemetry: U.S. Geological Survey, National Park Service (NPS), and the Conservancy of Southwest Florida researchers implant radio transmitters in “scout snakes” that lead them to other pythons during breeding aggregations. The snakes are subsequently captured and humanely killed.

- Pheromones and Traps: Researchers developed large traps for Burmese pythons designed to avoid non-target animals. While thus far unsuccessful, researchers found that male Burmese pythons recognize and follow female scent trails (pheromones), which could be used as a management tool to lure pythons into traps (Reed et al. 2011; Richard et al. 2019).

- Team Effort: South Florida Water Management District (SFWMD; Python Elimination Program), and FWC (Python Action Team Removing Invasive Constrictors) support a network of paid contractors who are trained to identify, search for, and safely capture and remove Burmese pythons throughout southern Florida’s public lands. Several other agencies have staff who conduct removal in the region.

- Raising Awareness: ENP implemented Don’t Let it Loose signage in the park to raise awareness about invasive species, and partner agencies continue to spread this message. FWC started an Exotic Pet Amnesty Program that allows owners to relinquish their exotic pets, including pets held illegally, without fees or penalties.

Lessons Learned

Detection dogs and eDNA are effective strategies to determine the presence of Burmese pythons, but both have limitations. Detection dogs could only search five miles per day due to heat (they cannot sniff while panting). However, dogs were more effective at detecting snakes than humans and completed their searches 2.5 times quicker. eDNA is useful for determining the presence or absence of python DNA in a water sample but data are difficult to interpret due to water flow and other confounding factors. Additionally, biologists still have to pinpoint the exact location of the snake after confirmation with eDNA or a detection dog in order to remove it.

Live traps have been ineffective at capturing Burmese pythons. Food-baited traps were unsuccessful, likely because Burmese pythons are ambush predators and food is not limited in the region. Pheromones can potentially be useful for attracting pythons to traps, but only during the breeding season and more research is needed to determine whether this technique will be successful.

Citizen science data is useful, however, most python sightings occur on canal levees or private roads, a small percentage of southern Florida, where access is easy and snakes are more detectable. The frequency of Burmese python detection in ENP is approximately one python per eight hours of searching, though it varies substantially over the year (Falk et al. 2016). Approximately 15,000 pythons have been reported to FWC and removed since 2000, with over 9,000 of those removals from contractors using visual survey methods. Ultimately, a combination of detection methods is necessary to successfully locate and remove Burmese pythons.

Collaboration among partners and the public is necessary to increase awareness and make timely and cost-effective progress towards controlling Burmese pythons across southern Florida. Regular communication is crucial to keep all partners informed about Burmese python control and to coordinate efforts. The FPCP will help with continued communication and collaboration.

Next Steps

- Enhance detection and removal tools for Burmese pythons, including implementing the use of innovative tools such as near-infrared cameras

- Conduct research to understand Burmese python vital rates such as age/size-specific survival, age at maturity, sex ratios, reproduction, population size, growth rates, and dispersal

- Maintain communication and working across agencies and organizations to collaboratively address invasive pythons throughout southern Florida

- Increase public engagement and education to enhance awareness about the impacts of non-native species in southern Florida

- Publish a peer-reviewed synthesis that 1) summarizes current knowledge of Burmese python biology and tool development, 2) uses the best science to evaluate management options, and 3) lays out a path for future research investment to aid management and research efforts

Resources

- Florida Python Challenge®

- Federal Lacey Act: Burmese Pythons as injurious

- Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission Article: Burmese Python Management in Florida

- National Park Service Article: Burmese Python Management in Florida

- 2021 Florida Python Control Plan

- Dorcas et al. (2012). “Severe mammal declines coincide with proliferation of invasive Burmese pythons in Everglades National Park.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 109(7): 2418-2422.

- Nafus et al. (2020). “Estimating detection probability for Burmese pythons with few detections and zero recaptures.” Journal of Herpetology 54(1): 24-30.

- Reed and Snowet al. (2014). “Assessing risks to humans from invasive Burmese pythons in Everglades National Park, Florida, USA.” Wildlife Society Bulletin 38(2): 366-369.

- Reed et al. (2011). “A field test of attractant traps for invasive Burmese pythons (Python molurus bivittatus) in southern Florida.” Wildlife Research 38(2): 114-121.

- Reed et al. (2012). “Ecological correlates of invasion impact for Burmese pythons in Florida.” Integrative Zoology 7(3): 254-270.

- Richard et al. (2019). “Male Burmese pythons follow female scent trails and show sex-specific behaviors” Integrative Zoology 14(5): 460-469.

- Willson et al. (2011). “Identifying plausible scenarios for the establishment of invasive Burmese pythons (Python molurus) in Southern Florida.” Biological Invasions 13(7): 1493-1504.

Contacts

- McKayla Spencer, Interagency Python Management Coordinator, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission: mckayla.spencer@myfwc.com

- Sarah Funck, Nonnative Fish and Wildlife Program Coordinator, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission: sarah.funck@myfwc.com

- Kevin Donmoyer, Invasive Species Biologist, Everglades National Park: kevin_donmoyer@nps.gov

- Bryan Falk, Supervisory Invasive Species Biologist, South Florida Natural Resources Center, Everglades and Dry Tortugas National Parks: bryan_falk@nps.gov

- Tylan Dean, Chief of Biological Resources, Everglades and Dry Tortugas National Parks: tylan_dean@nps.gov

- Dan Kimball, Superintendent, Everglades and Dry Tortugas National Parks (retired): danbkimball@gmail.com

- Lisa Thompson, Public Information Specialist, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission: Lisa.Thompson@MyFWC.com

CART Lead Authors

- Daniel Velasco, CART Student Author, University of Arizona

- Mayra Hernandez, CART Student Author, University of Arizona

- Krystie Miner, CART Research Specialist, University of Arizona: kminer@arizona.edu

Suggested Citation

Velasco, D., Hernandez, M., Miner, K. A. (2022). “Managing Non-Native Burmese Pythons in Southern Florida.” CART.Retrieved from https://www.fws.gov/project/managing-burmese-pythons-florida.