About Us

It's quiet and peaceful. In winter, nearly silent. In summer, listen for insect music. The sky is big, the space vast. It invites you to explore. Bring along your curiosity.

Desert

Surprising to most people outside the Northwest, the landscape of eastern Washington is that of a desert. In its natural state, almost all of Columbia National Wildlife Refuge would be considered desert, with the exception of the naturally ephemeral Crab Creek. However, rather than a desert of cacti and mesquite, eastern Washington's desert is that of shrub-steppe, with sagebrush sagebrush

The western United States’ sagebrush country encompasses over 175 million acres of public and private lands. The sagebrush landscape provides many benefits to our rural economies and communities, and it serves as crucial habitat for a diversity of wildlife, including the iconic greater sage-grouse and over 350 other species.

Learn more about sagebrush and bunchgrasses.

Water

Like most of eastern Washington, much of the refuge is no longer in its natural state. The construction of the Columbia Basin Project forever altered the landscape, bringing water to the desert. Seepage from irrigation structures and reservoirs created wetlands, riparian riparian

Definition of riparian habitat or riparian areas.

Learn more about riparian areas and small lakes on the once-dry landscape. The seasonal Crab Creek has become perennial, even providing habitat for endangered salmonids.

Ice Age Floods

The creation of lakes and wetlands would not have happened without the geologic upheavals of ages past. During the last Ice Age, sheets of ice spreading down from Canada blocked rivers with dams of ice. Occasionally—or perhaps hundreds of times—the dams failed, sending floodwaters greater than the flow of all the world's rivers combined tearing across eastern Washington's lava fields, gouging coulees, redistributing boulders, depositing massive sand and gravel bars, scraping the land bare in some areas and leaving behind rich soils elsewhere. Nowhere are these depressions and geologic nooks more prevalent than on the refuge. In turn, this torn-up land—the Drumheller Channeled Scablands, National Natural Landmark National Natural Landmark

The National Natural Landmarks Program preserves sites illustrating the geological and ecological character of the United States. The program aims to enhance the scientific and educational value of the preserved sites, strengthen public appreciation of natural history and foster a greater concern for the conservation of the nation’s natural heritage. The program was established in 1962 by administrative action under the authority of the Historic Sites Act of 1935. The first National Natural Landmarks were designated in 1963. Today, there are more than 600 National Natural Landmarks in 48 states, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Learn more about National Natural Landmark —formed just the right topography to capture the new hydrology of the Columbia Basin Project, creating wetlands in the desert.

Water Brought Wildlife

Water in the desert means an abundance of life. In its original state, the land supported coyotes, rattlesnakes, mule deer, horned larks, sage sparrows and other creatures of the shrub-steppe, although densities were limited. Water has changed all this, however. Many of the naturally occurring species can be found at higher densities (e.g., mule deer). Other species are newcomers, totally dependent on the artificial water; black-necked stilts and American avocets are some of the flashier ones. Still more species that may have made an occasional appearance can now be found in great numbers—Canada geese, northern pintails, and the refuge's most famous visitors, lesser Sandhill cranes. It was because of this newly created wildlife oasis, and the need to provide suitable mitigation for the Columbia Basin Project, that the refuge was created in 1944 "for migratory birds and other wildlife."

Water Brought Recreation

Another thing that water brings is recreational use. Without water, there wouldn't be any fishing,waterfowl hunting, or boating. It's likely that there would be less hiking, biking, horseback riding, or sightseeing; visitors are drawn to water and the vegetation and wildlife it fosters. Water brings the Sandhill cranes, the migrating songbirds and the waterfowl that people come to see, learn about and find for their "life-lists." It provides the serenity and the visual contrasts that draw the eye, and then the feet, of visitors. Without water, recreation and visitor use would be dramatically less on Columbia National Wildlife Refuge.

Farmlands

The Columbia Basin Project did more than create the need for, and provide water to, the refuge. It also created irrigated farmland, which secondarily provided a food source for many of the refuge's species. For example, the great concentration of Sandhill cranes found on the refuge in the spring is a recent event, beginning in earnest in the late 1980s. Before then, the cranes likely passed through the area on their way to breeding grounds in south-central Alaska without more than a brief stop. Now, leftover grain in farmers' fields has become an important food source for migrating cranes, concentrating them by the thousands for several weeks in late winter and early spring. Other wildlife, most notably migrating waterfowl, mule deer and numerous rodent species, also take advantage of the harvest. While much of the habitat found on the refuge (most of the lakes, wetlands, springs and perennial streams) is the result of an artificial infusion of water, it is important to note that the habitats themselves are not artificial. Natural wetlands and shallow lakes can be found within the Columbia Basin, and those on the refuge function the same way as naturally occurring ones found elsewhere within the area. So, while many of the habitat types on the refuge would naturally be found in far smaller acreages, if at all without seepage water from the Columbia Basin Project, the only non-natural habitat types present are farm fields and moist soil management areas.

Our Mission

The mission of the National Wildlife Refuge System is “To administer a national network of lands and waters for the conservation, management, and where appropriate, restoration of the fish, wildlife, and plant resources and their habitats within the United States for the benefit of present and future generations of Americans.”

Columbia NWR’s mission (refuge purpose) is to be “a refuge and breeding ground for migratory birds and other wildlife” and “an inviolate sanctuary, or for any other management purpose, for migratory birds.”

Other Facilities in this Complex

The four refuges that make up the Central Washington National Wildlife Refuge Complex have little in common, other than being in the state of Washington. That makes the Complex a wonderfully diverse blend of habitats, species, and recreational opportunities. There’s something to be found by everyone that will pique their interest or pull them into the landscape. A geology buff? Visit Columbia National Wildlife Refuge, carved by the great floods of the last ice age. Need a scenic landscape to paint or simply unwind in? Conboy Lake is the spot. Interested in our history? The Hanford Reach National Monument is the place to investigate. Want to add to your birding life list? Check the spring and fall migrations through Toppenish.

Conboy Lake National Wildlife Refuge

Nestled near the foot of snow-capped Mount Adams in Washington’s Cascade Range, Conboy Lake National Wildlife Refuge is a scenic gem within the National Wildlife Refuge System. The refuge encompasses 6,574 acres of lush seasonal marshes and vibrant forested uplands that beckon to both visitors and wildlife. A blend of wetlands; grassy prairies; streams; and oak, pine, and aspen forests supports a diverse wildlife community. The rich habitat sustains thriving populations of migrating waterfowl and songbirds. The rare Oregon spotted frog breeds in wetlands throughout the refuge. Elk are plentiful and frequently seen along refuge roads. Conboy Lake also supports most of the breeding population of greater Sandhill cranes in Washington. As a national wildlife refuge national wildlife refuge

A national wildlife refuge is typically a contiguous area of land and water managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for the conservation and, where appropriate, restoration of fish, wildlife and plant resources and their habitats for the benefit of present and future generations of Americans.

Learn more about national wildlife refuge , this living system will satisfy your longing for splendor and serenity, just as it did for the indigenous peoples, explorers, loggers, and ranchers who were first drawn to the valley’s plentiful resources.

Hanford Reach National Monument

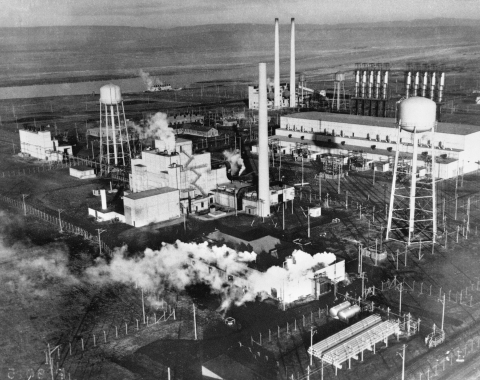

Thousands of acres of land along the Hanford Reach of the Columbia River and the Saddle Mountain National Wildlife Refuge became the Hanford Reach National Monument in 2000 to protect rare plants, wildlife, and remnants of human history. The 196,000-acre Monument is open, treeless country punctuated by steep rolling hills and canyons. Since 1943, what are now Monument lands have been a safe haven for important and increasingly scarce natural and cultural resources. The lands were allowed to remain wild because they served as a security buffer for the top-secret Manhattan Project during World War II, which produced plutonium for atomic weapons. With limited development and grazing, native plants and animals thrived, and a diverse archaeological record has been preserved. The Monument supports 725 vascular plant species—at least 47 of which are species of conservation concern—42 species of mammals, more than 200 species of birds, 9 reptile and 4 amphibian species, 45 species of fish, and over 1,600 species of insects.

Toppenish National Wildlife Refuge

Toppenish National Wildlife Refuge, established in 1964, is an important link in the chain of feeding and resting areas for waterfowl and other migratory birds using the Pacific Flyway. Although Toppenish was established primarily for migratory waterfowl, many other migratory and resident wildlife species live here, such as American bitterns, peregrine falcons, badgers and beavers. The refuge is a broad collection of habitats supporting a diversity of species. Natural wetlands, such as sloughs and oxbows, and artificial wetlands are flanked by riparian riparian

Definition of riparian habitat or riparian areas.

Learn more about riparian areas. Many species of migratory waterfowl and nongame birds, such as Virginia rails and savannah sparrows, use the wetlands for feeding and nesting activities. Native shrub-steppe—characterized by greasewood, Wyoming big sage, rabbitbrushes, bitterbrush, and native bunchgrasses, such as Great Basin wildrye, Indian ricegrass, Idaho fescue, and Sandberg bluegrass—once covered the upland areas. Loggerhead shrikes, long-billed curlews, California quail, Brewer’s and sage sparrows, and sage thrashers are only some of the animals that use the shrub-steppe. This diverse combination of habitats is a natural magnet to migratory and resident wildlife, alike.