A parasitic eel-like fish with a gaping mouth, the rarely seen Pacific lamprey is often vilified. In reality, they provide an important service in our local California waterways. This native creature cleans our rivers, delivers food to the water system with marine nutrients and provides sustenance to tribes.

“They can be scary-looking, slimy, and they are nocturnal, so you don’t know what’s going on; some people see them as ‘blood-sucking lampreys,’” said Damon Goodman, fish biologist with the Arcata U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service office. “People think: 'what if they grab ahold of me?'"

The fact is Pacific lamprey only filter-feed in freshwater systems, eating microorganisms and helping to clean the water. When they are first born, they are about the size of an eyelash and burrow in the stream bottom for five to seven years. Once they are about the size of a pencil, they transform, developing eyes, teeth and a sucker mouth. Then they migrate out to the ocean to feed parasitically on whales, pollock and other fish. They grow to about two feet long before returning to fresh water to spawn.

With their ability to travel farther into the river system than Chinook salmon or steelhead, Pacific lamprey, which can live up to 11 years, also help increase ecosystem productivity.

“When they come up to spawn and die, all that energy is released back into the system, which drives macroinvertebrate production, providing bugs for other fish and birds to eat,” said Goodman who did his Master’s thesis on Pacific lamprey at Humboldt State University (HSU). “They construct these nests in the cobbles, grab rocks using their suctorial disks (mouths) and move them to form a ‘fire ring’ for their eggs, creating topographic diversity in the channel.”

Bald eagles, river otters, bears and raccoons also feed on lampreys.

Unfortunately, the number of lampreys has declined in rivers throughout the state. As recently as the 1990s, Pacific lampreys occupied larger freshwater streams as far south as northern Baja California, Mexico. However, by 2016 they were absent south of Big Sur. To the north, lampreys are still present along the coast to Alaska.

Goodman along with Dr. Stewart Reid from Western Fishes got together to work with partners throughout the state, including the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, to try and reverse the trend, and avoid placing the species on the federal Endangered Species List.

“A lot of what we have done is an approach to conservation,” Goodman said. “We’re trying to get ahead of the game, by identifying problems and where we can get the most bang for the buck – practical, low cost approaches to solutions to assist the species.”

Goodman and Reid found a low-cost solution at the Van Arsdale Fisheries Station in Potter Valley, California, where only six percent of lampreys were making it through the fish ladder, and with a great deal of exertion. Fish ladders are designed specifically for fish that jump such as salmon or steelhead, presenting a challenge for a non-jumping fish like the Pacific lamprey.

“People might ask ‘can’t they just get over the dam,’ well they were getting over the dam but it was taking three to four weeks and only a small fraction were successful,” Reid said. “If you had to spend three weeks to get into your house, you’d probably look for a solution as well.”

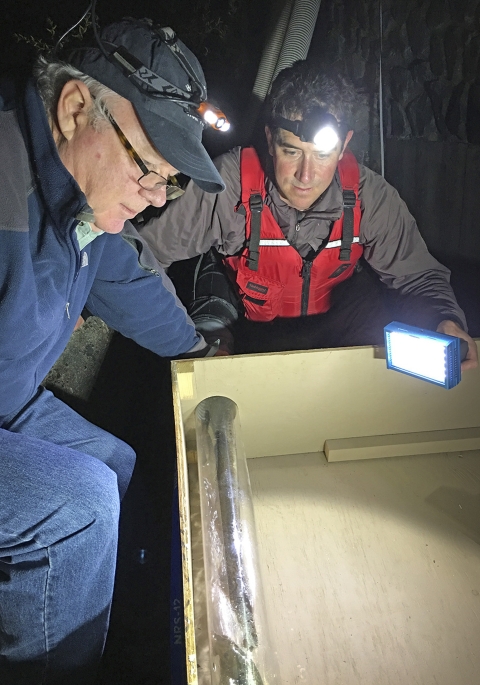

The Van Arsdale project, which cost less than $3,000 in materials, helps lampreys get through to the upper Eel River through four-inch PVC tubing bought at a local hardware store. The project also includes a camera and a computer to monitor the number of lampreys going through the tube.

“All the lampreys that go up the tube get counted and measured, so, for very little cost we get a really effective monitoring system,” Reid said. “This is the first time we are able to get numbers from the monitoring. We already found that the average time to get up the tube is three hours.”

The project which started in 2015 will get a full-year look by July 2017.

“We had no evidence that this would work,” Goodman said. “No one has ever put lampreys up a tube, much less a 50-foot climb across 300 feet of tube. We wondered whether this was going to actually work.

“It was a really cool feeling seeing the first one pop out of the top. There were high-fives all-around. We figured if they are using their suctorial disks to climb up, why couldn’t they climb up a tube.”

The result is near perfect success through the tube.

“I’ve been working with young salmon for 23 years, so when this popped up as something that needed to be addressed, I was really quite happy,” said Scott Harris, environmental scientist in fisheries biology for CDFW who has been at Van Arsdale for eight years. “Their whole life history and biology is just so different from any other fish. We’re learning something different every day, dealing with the lampreys.

“The Eel River is named after lampreys and I think it is pretty cool that we have had a two-year success of giant runs of the river’s namesake.”

Working with the National Marine Fisheries Service and PG&E, the Van Arsdale project started as a process to speed up the timing of juvenile Chinook salmon getting out of the project area. During the first block water release in 2012 Harris became aware of the lampreys.

“They went pretty crazy that very first year and were quiet for a few years and in 2016 it absolutely blew up,” said Harris of the numbers of lampreys that year.

In 2012, Goodman got wind of what was taking place and gave Harris a call to start the process of creating a passage and setting up a process to monitor them.

The importance of this project and efforts made by Goodman, Reid, Harris and the Pacific Lamprey Conservation Initiative, including over 300 partners, cannot be understated. In addition to helping improve river health, the lampreys provide an important cultural benefit to local tribes.

“The Hoopa Valley Tribe have been fishing for salmon, sturgeon and lamprey since time immemorial,” said Sean Ledwin, habitat division lead for Hoopa Valley Tribal Fisheries.

“Lamprey in particular are of real interest," he said. "Tribal people start fishing for eels in winter months at the mouth of the Klamath using eel hooks and then in the spring there’s upstream fishing with eel baskets. It is the first push of fish that come in after a long wet winter. Lampreys are incorporated into some of the ceremonies and dances for the tribe.”

Tim Nelson, natural resources director for the Wiyot Tribe, added, “Our elders tell me stories about how they used to just go down to Benbow dam and fill their gunny sacks up in minutes with lampreys and a couple of years ago we were lucky if we caught one or two at the mouth of the Eel."

"These last couple of years we’ve had some really good runs of Pacific lamprey, and we’ve been able to tell our elders the specific reasons and more about the life cycle of the lamprey," he said. "When they go out eeling now, they feel even more of a connection.”

The efforts at Van Arsdale are one of many projects Goodman and Reid are spearheading. For example, a climbing surface made from $300 of recycled material in 2013 helped bring lampreys back into the creek in Mission Plaza in San Luis Obispo, California.

Also, Caltrans Engineer Kristine Pepper now considers lampreys in design of weirs. After seeing a one-hour presentation in 2013 by Goodman for biologists with Caltrans, Pepper decided to incorporate it in a project at Cedar Creek, a tributary of the South Fork of the Eel River. In collaboration with Goodman, she developed a lamprey fish passage fish passage

Fish passage is the ability of fish or other aquatic species to move freely throughout their life to find food, reproduce, and complete their natural migration cycles. Millions of barriers to fish passage across the country are fragmenting habitat and leading to species declines. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's National Fish Passage Program is working to reconnect watersheds to benefit both wildlife and people.

Learn more about fish passage weir to be included for the Cedar Creek project and future projects within Caltrans District 1.

“He put it in my mind that there are other creatures to think about,” said Pepper. “I would not want to inhibit any natural process what-so-ever. If something is passing through an area I don’t want to be responsible for changing patterns, whether it is endangered or not. I believe in looking at the whole system.”

The Cedar Creek project is slated for construction in the summer of 2017.