Recent hurricanes Harvey and Irma brought to the forefront the need-- more than ever-- to protect coastal areas.

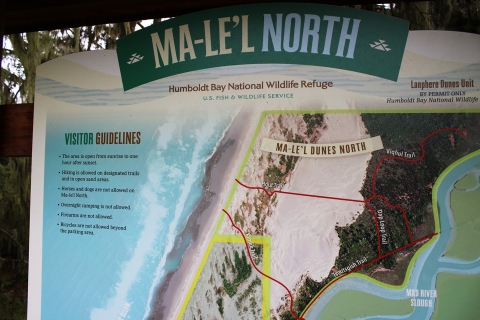

The staff at the Humboldt Bay National Wildlife Refuge have been studying the dunes in the northwest portion of California for more than 30 years, most recently to assess what can be done to make them more resilient to sea level rise and extreme weather events. One of the solutions: the removal of invasive European beach grass and the restoring of native plants more resistant to severe coastal storms.

“The dunes here are already unique,” said refuge manager Eric Nelson, a northern California native who started his career on the Humboldt Bay refuge before working at several refuges in the west and returning over 10 years ago. “The spread of invasive plants and changes in the dune system up and down the west coast have pretty much left this area (the refuge and neighboring public lands) one of largest remaining areas of native dunes along the entire west coast of the United States. It is already rare. We are not only trying to expand the native system here but also learn how the native system is resilient.”

A recent 5-year collaborative research project to understand sand behavior as it relates to the dunes is being conducted for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and many partners. The study covers a 52 kilometer stretch of coastline from Trinidad, California, in the north to Centerville beach in the south, known as the “Eureka littoral cell.”

“The reason we are looking at such a large area is because all parts of the littoral cell are interconnected,” said Andrea Pickart, ecologist for the Humboldt Bay National Wildlife Refuge. “To look just at our piece of land would be short-sighted. Instead we are collaborating with public and private landowners all along that stretch of shoreline. First, trying to understand what is happening now, and then, based on the measurements we take we’ll be able to model what we can expect in the future as the sea level rises.”

“Andrea and others have learned a ton about dune ecology,” said Nelson. “She’s been working with these researchers for seven years now and this is the natural progression of science. One question or hypothesis leads to another and you do the research to test the hypothesis.”

The project is important for partners and local landowners who have a vested interest in the land. Partners on the project include: California State Coastal Conservancy (who funded the first half of the project), Bureau of Land Management (who matched that funding), California State Parks, California Department of Fish and Wildlife, Friends of the Dunes, Wiyot Tribe, Humboldt Bay Municipal Water District, Humboldt Bay Harbor Recreation and Conservation District, Wildlands Conservancy and academic partners - Dr. Ian Walker from Arizona State University and Dr. Patrick Hess from Australia.

“The partners and researchers are on board because they want to see what the future holds for the dunes and Humboldt Bay,” said Nelson. “The dunes make up the spits for Humboldt Bay. As the dunes go, so goes the bay, ultimately. There have been a lot of changes in the ecology of this area in the last 200 years whether it is flows and sediment coming out of Eel River, the dunes themselves, the invasive plants, or jetties in the bay.”

“The dunes are the barrier that protects Humboldt Bay, which is both an area of commerce, and an incredible area of natural diversity,” said Pickart. “That’s the bottom line. The dunes themselves contain endangered plant communities, birds, mammals, and insect communities that provide a wealth of biodiversity. With a changing climate the greater genetic diversity you have, the more adaptive capacity you have. More genes mean more ability to adapt to change.”

Dr. Walker, who has been working in dune systems of the Pacific Northwest since 2000, starting with Alaska and making his way down the coast through British Columbia and eventually to the dunes at Humboldt Bay, agrees: “These dunes provide critical barriers to and protection from storm surge, erosion, and ongoing sea-level. As is recognized elsewhere in the world, the maintenance and restoration of resilient dunes is a significant part of developing effective erosion mitigation plans and climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change adaptation strategies. The diversity and richness of our partnership collaboration on this project is among very few new initiatives in the U.S. and is an incredibly encouraging step forward.”

The researchers believe that one of the biggest issues facing the western coast today is the spread of a non-native plant – known as European beach grass. When European beach grass invades, it creates a monoculture and the populations of native plants, invertebrates, mammals, and birds all suffer.

Removal of the dense grass allows the native plants to recover, including a native dune grass that grows less densely than the beach grass. Native plants allow more sand to move through and over vegetated dunes, which is critical to maintaining the integrity of the dunes as they migrate.

“It’s not only important from a sediment perspective, it’s important to all the plant communities on the dunes because all of those plants, including the endangered ones, are adapted to sand movement,” said Pickart. “If you freeze the sand movement the plants are no longer competitive. So you end up losing your plant community--and these are globally endangered plant communities.”

“In this research project we are also measuring how different vegetation types affect how the sand is moving, comparing restored dunes to invaded dunes,” she said.

Besides countless invertebrates whose habitat could be affected, other mammals including grey foxes, skunks, brush rabbits, jack rabbits, porcupines, field mice, voles, and shrews would be impacted.

Additionally impacted by the invasive European beach grass are solitary bees, such as Silver bees and leafcutter bees, that can pollinate both crops for agriculture and native plants.

Solitary bees, unlike honey bees, nest in a hole in the ground and do not have hives. The female burrows down and lays her eggs, provisions them and leaves.

“When European beach grass comes into an area, it completely covers the open sand that they are nesting in. The bees lose their habitat and disappear, and you lose an important tool for agriculture,” said Pickart.

Pickart’s main concern is future erosion that accompanies more severe storms during El Niño or La Niña years. “If you have a very stable fore dune that is being repeatedly eroded without enough time to build back up, and none of the sand is moving inland, you are basically are going to start losing volume in your dune system,” she said. “That is the theory that we are testing. We have created a demonstration site to test how well the restored dunes adapt to sea level rise.”