This year is the 50th anniversary of the Endangered Species Act, a law that has been a powerful catalyst for conservation of America’s most treasured fish, wildlife, plants and their habitats. In the Pacific Region, our Tribes, state and federal agencies, and partners have joined with our dedicated staff to be the driving force behind the successes we share and the strength ensuring we can address the challenges ahead. Celebrate this milestone with us in this collection of stories as we reflect on past successes, assess current challenges, and envision an equally bright future for the next 50 years and beyond.

After 60 years of collaborative conservation efforts among federal, state, non-governmental organizations, and local partners, the Hawaiian Goose, or nēnē , may be one step closer to recovery. An intensive captive breeding program, habitat restoration, and active management strategies have led to the nēnē return from the brink of extinction. As a result, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has proposed downlisting the nēnē from endangered to threatened under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

“It took decades of hard work and remarkable partnerships to bring nēnē back from the brink of extinction,” said Robyn Thorson, regional director for the Service’s Pacific Region. “Collaborative conservation efforts like this are the key to success in protecting and recovering Hawaii’s native species.”

One of the pressures that nēnē face are invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

Learn more about invasive species . Introduced invasive predators like mongooses, rats, dogs, cats and pigs all were factors that led to the first substantial declines of nēnē. Nēnē are highly vulnerable to predation when nesting. During nesting season, nēnē molt their feathers and are flightless making them easy prey for predators. Ongoing predator control, habitat management efforts, and collaborative conservation will continue to be important for nēnē to continue on the road to recovery.

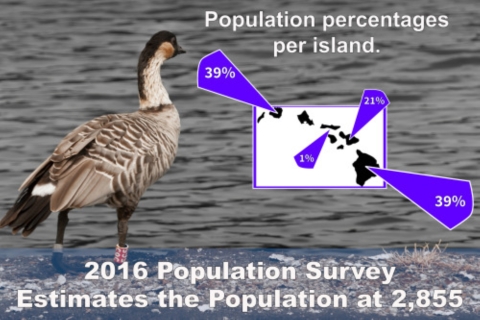

By the mid-twentieth century, fewer than 30 nēnē remained in the wild on a small area on the island of Hawai‘i. A further 13 birds survived in captivity. The nēnē was listed as an endangered species in 1967, and in the decades following, some 2,800 captive-bred birds were released at more than 20 sites throughout the main Hawaiian Islands. The release of captive-bred nēnē on national wildlife refuges, national parks and state and private lands saved the species from imminent extinction.

Captive breeding has contributed to the ongoing recovery of nēnē throughout the Hawaiian Islands. The captive propagation of nēnē was a multi-tier effort that involved national and international conservation agencies.

The State of Hawaii, Peregrine Fund, Waterfowl and Wetland Trust, San Diego Zoo and private landowners all recognized the possibility of a potential nēnē extinction. Each of their captive breeding programs helped preserve the species and aided conservation managers with the recovery effort and eventual release of nēnē back into the wild.

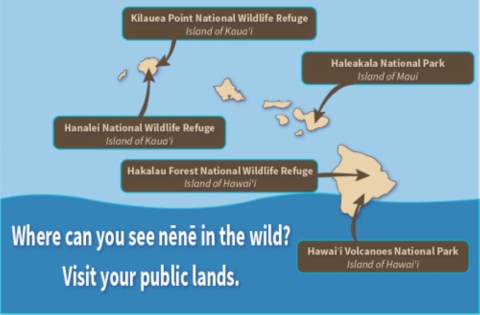

Today more than 2,800 individuals survive, with stable or increasing populations on Kauai, Maui and Hawaii Island and an additional population on Molokai.

As nēnē increase in numbers and expand their range, they face increased interaction and potential conflict with landowners and businesses. In addition to the downlisting, the Service is proposing a rule that would allow additional flexibility for landowners to manage nēnē on their property. This rule, under section 4(d) of the ESA, allows some types of actions that are normally prohibited under the ESA as long as those actions are consistent with conservation of the nēnē. If the proposed downlisting is finalized, the rule would give landowners management flexibility without reducing the effectiveness of conservation actions or the recovery of the species.

Establishing a healthy population of nēnē in Hawaii requires flexibility, support and partnership with private landowners. Working with private landowners helps conservation managers maintain nēnē populations on both public and private lands. Private landowners like the Shipman Ranch allow for greater conservation management of nēnē on their land and neighboring release sites.

To further strengthen the connection with the community, the Service signed a Memorandum of Agreement with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). Partners like Shipman Ranch and NRCS creates an innovative collaboration between the Service and private landowners that will benefit the nēnē recovery effort.

The State of Hawaii is an essential partner in the recovery of nēnē , helping lead the way with innovative conservation efforts, including the formation of the nēnē Recovery Action Group. This group is comprised of experts from state and federal agencies and has an important role in identifying nēnē conservation actions and priorities.

Collaboration is the key to success in recovering imperiled wildlife. The Service is actively working with diverse partners to conserve imperiled species and to work toward fully recovering them so they can be removed from listing under the ESA. Downlisting species as they meet their recovery goals ensures we are continuing to use our resources to protect the most at-risk species.

###

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service works with others to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, plants, and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people. For more information, visit www.fws.gov/pacificislands, or connect with us through any of these social media channels at https://www.facebook.com/PacificIslandsFWS, www.flickr.com/photos/usfwspacific/, https://medium.com/usfwspacificislands or www.twitter.com/USFWSPacific.