Jacksonville, North Carolina — Above the distant din of 50-caliber machine gun fire

and Cobra attack helicopters, John Hammond hears the unmistakable sound of a red-cockaded woodpecker. He is approaching Combat Town, where U.S. Marines routinely assault a mock Iraqi village at Camp Lejeune.

It is an incongruous spot for an endangered bird to make its home – the middle of a war zone where artillery boom and tanks prowl. Nothing, though, seems out of the ordinary to Hammond, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

The National Military Fish and Wildlife Association holds its annual meeting in Norfolk, Va. from March 25-30. The training workshop gathers wildlife biologists and natural resource officers from across the country to discuss environmental issues impacting military installations. It is held in conjunction with the North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference.

“They do co-exist, absolutely,” said Hammond, who previously worked as the base’s endangered species coordinator. “The woodpeckers get along well with Combat Town. As long as they can find their groceries and a place to stay they’re fine.”

Under a new, unique and far-reaching state-federal partnership, the woodpeckers’ health and well-being is inextricably tied to the U.S. Marine Corps mission at Lejeune. An agreement between the military, the Service, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and the state of North Carolina allows Lejeune to expand training through prime woodpecker territory. In return, the so-called Recovery and Sustainment Program, or RASP, should boost the woodpecker population across eastern North Carolina.

The timing is propitious: the Service is currently deciding whether to de- or downlist the woodpecker or keep it as an endangered species. A decision is expected later this year.

The official RASP roll-out is planned for April at a nearby state wildlife management area wildlife management area

For practical purposes, a wildlife management area is synonymous with a national wildlife refuge or a game preserve. There are nine wildlife management areas and one game preserve in the National Wildlife Refuge System.

Learn more about wildlife management area whose woodpecker population should grow considerably due to the Lejeune agreement. And, from March 25-30, natural resource officials from military bases around the country will gather in Norfolk, Virginia to share conservation success stories. RASP, and the wily woodpecker, should figure in those discussions.

“The base isn’t going to grow any more land, but we still need areas that tanks can run through, that we can shoot live fire and that we can blow things up,” said Chip Olmstead who manages the firing ranges and training areas at Lejeune. “People might think that live fire and woodpecker habitat are mutually exclusive. But this program shows we can work together without jeopardizing either one.”

Waiting for the ruckus to subside

Camp Lejeune sprawls over 156,000 acres along the New River and the Atlantic Ocean, an ideal spot for sailors and Marines – and red-cockaded woodpeckers. The birds thrive on the base’s extensive longleaf pine forests which once covered 90 million acres in a swath stretching from Virginia to Texas.

Timber, turpentine, agriculture and urban development decimated the longleaf forests. Today, commercial plantations of fast-growing loblolly or slash pine predominate. Maybe 4.5 million acres of longleaf remain.

The Service lists 31 threatened or endangered species that depend upon the fire-resilient trees, including the eastern indigo snake and Cooley’s meadowrue, a perennial herb. The red-cockaded woodpecker joined the endangered list in 1970, one of the first federally protected species.

The smallish black and white bird (with barely visible red marks on the male’s head) requires living pines for roosting and nesting. They seek resin-y trees where the sticky goo deters snakes and other animals from crawling into their cavities. They prefer older pine trees, like longleaf which can live up to three hundred years. Federal lands, military bases in particular, are about the only place to find old-growth longleaf.

Blue-banded trees, signifying woodpecker cavities, surround Combat Town. The birds flit from tree to tree when the low-slung, dun-colored collection of modified shipping containers isn’t under attack. When Marines on patrol approach the town, the birds hunker down or fly away and wait for the ruckus – tanks, trucks and blanks, not bullets – to subside.

“Woodpeckers are not, necessarily, averse to people or noise,” said Craig Ten Brink, a civilian wildlife biologist at Camp Lejeune. “If we start losing RCW habitat around Combat Town, some of those clusters might blink out. But if we continue to maintain good habitat, I imagine most birds will stick around.”

The woodpecker’s listing, at first, proved a formidable foe for the Marines. Training across the pine forests and pocosin swamps of Lejeune – and other southern bases – could have been threatened. Lejeune, by virtue of its location and mission, became ground zero for the bird’s recovery.

Most of eastern North Carolina had been cleared of longleaf for agriculture, development or loblolly plantations. Live-fire exercises burned thousands of acres over the years leaving a fecund understory of wiregrass and bluestem prized by RCWs.

In 1986, only 32 woodpecker clusters remained on Lejeune. (A cluster is a bunch of trees with RCW cavities; each cluster contains maybe three or four birds.) A circle 200-feet wide was painted white around each cavity tree to warn troops away from the birds’ homes.

Fish and Wildlife and the military developed a plan to save the woodpecker and allow artillery, small-arms and armored-vehicle training at Lejeune. Each RCW population milestone would be rewarded with fewer buffered trees and more room to train. The ultimate recovery goal: 173 clusters.

In 2011, Lejeune tallied 100 clusters. Ten Brink says 128 clusters currently call the base home.

Growing the species

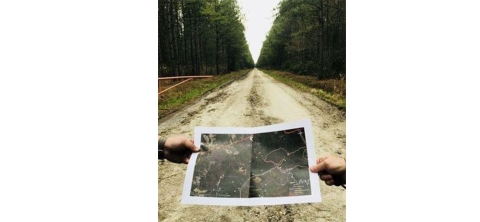

The dirt road just a few miles below Camp Lejeune runs arrow-straight through the past, present and future of conservation forestry.

On one side stands row upon row of near-identical 20-foot high loblolly pines awaiting, one day, the woodcutter’s blade. On the other, a mish-mash of various-sized longleaf pines interspersed with wiregrass, fetterbush, bigleaf gallberry and other plants that mimic a historically natural eastern forest.

The Bear Garden tract is part of the 47,700-acre Holly Shelter Game Land owned by North Carolina along the Northeast Cape Fear River. Fish and Wildlife, the Nature Conservancy and others expect to turn much of the wildlife management area into a longleaf pine forest that woodpeckers – and song birds, migratory birds, quail, turkey and deer – love. RASP money will make it happen.

“Usually, restoration projects are rarely over a few thousand acres and this project will be maybe 10 times that amount,” said Casey Phillips, the coastal RASP forester for the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission. “This is a large-scale partnership with dedicated funding which is somewhat novel.”

Today, about 45 clusters of woodpeckers dot the game lands. RASP aims to add 60 more to Holly Shelter and nearby Stones Creek Game Lands by, eventually, translocating the birds from other wildlife areas, like the Croatan National Forest. First, though, Holly Shelter must be transformed into RCW-friendly habitat.

The U.S. Navy has secured perpetual conservation easements on 15,000 Holly Shelter acres. The National Fish and Wildlife Foundation will manage the conservation fund and ensure that the tract is properly cared for to boost RCW clusters.

The Navy aims to set aside roughly $19 million for an endowment to manage the property for years to come. The wildlife commission, with new equipment and staff funded by the military, will regularly burn the land, plant wiregrass and other woodpecker-friendly habitat and monitor RCW populations.

“We’ve got the knowledge and tools to restore habitat, so RASP gives us a lot of confidence that we can grow up the species here again,” said Hammond, the Service biologist. “It will just take a lot of time because we need older, larger pine trees for the woodpeckers.”

An added benefit: RCW habitat will boost the already popular hunting grounds.

“We’re located near Wilmington and Jacksonville, and Raleigh is just a stone’s throw down the road,” said the commission’s Phillips. “There’ll be a tremendous response from wildlife – deer, quail, turkeys – as the young forest transitions to older forest.”

Camp Lejeune benefits too. The 60 clusters at Holly Shelter and Stones Creek allows the Marines to reduce their original on-base woodpecker goal of 173 clusters to 113 clusters – an amount the installation has already surpassed.

“Marines and red-cockaded woodpeckers both like the high ground, so we’re both fighting for the same turf,” said Olmstead who manages the base’s training lands. “The Marines need to get from the ship to the shore and move inland, to fire and maneuver, to Combat Town. It’s a capability we’re lacking now. RASP gives us a lot of flexibility to develop this capability.”

Lejeune can now expand into RCW territory to enlarge training areas. But it won’t curtail woodpecker recovery efforts on base, despite the addition of the game lands. RASP is the military’s insurance policy in case woodpecker trees or clusters are harmed.

“What’s cool about the program is that it allows certainty for training on base that probably wouldn’t have happened,” said Ten Brink, the base’s endangered species specialist. “While it lowers the recovery goal on base, it expands the landscape that we devote to recovery of RCWs.”