Some thought it was a lost cause.

When Lisa Heki took on Lahontan cutthroat trout recovery in Nevada’s Pyramid Lake in the 1990s, the fish had been missing from the iconic desert lake for half a century.

Generations of Pyramid Lake Paiute tribal members and the surrounding communities had passed without witnessing the largest inland cutthroat trout species, weighing in at upwards of 40 pounds. Gold Rush settlers in the 19th century told tales of abundant, 60-pound trout in the Truckee River upstream of Pyramid Lake. In those days, the fish could make the 120-mile swim to Lake Tahoe.

But Heki had hope.

“I have a lot of faith in a species’ ability, if you give it just a little bit of a chance,” she said.

The chance? In the late 1970s, taxonomist Robert Behnke identified a single population of fish that he thought could be the Lahontan cutthroat trout from Pyramid Lake. It was in a remote stream in the Pilot Mountains bordering Nevada and Utah. In the days before genetic tools that could distinguish between populations, he judged the species based on physical appearance, and figured they were likely transplanted from Pyramid Lake 40 years earlier.

Behnke wasn’t alone. Bryce Neilson, a Utah Fish and Game biologist, was also convinced that the strain was that of the ancient trout.

“He shepherded the Pilot Peak strain in Utah from the time of its discovery in 1977 to his contact with me,” Heki said. Neilson dug ponds near the stream to house the fish and build numbers through the 1980s.

Heki entered the picture in 1994, and has since devoted most of her 28-year career to restoring this strain, whose disappearance was closely tied to water storage and diversion projects that drastically changed the watershed.

She and a variety of partners with universities, the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe, and federal and state agencies took on the trout’s return from every angle: genetics and research, water management, habitat both in and along the waters, population restoration and recreational opportunities.

“DO WHAT YOU NEED TO DO”

Heki’s been fond of fish since her early years. At six years old and the youngest of five children, Heki’s job was to carry the stringer of fish and get them cleaned for dinner.

Fast forward to college, and Heki studied the non-native trout she once fished for. “It didn’t speak to me — the put and take aspect.” Focusing solely on fishing can overlook the conservation of native habitat and species, she said.

Professor Jim Deacon at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas, gave her an alternative. With him, she monitored woundfin minnows in the Virgin River and dove Devils Hole to count the paperclip-sized blue pupfish.

His conservation spirit was contagious, Heki said. She abandoned the other field of study — and the funding that went with it — to pursue work with native indigenous fish.

“These species and their aquatic habitats in Nevada are of particular interest to me, and the conservation of those is what motivates my day to day,” she said.

Heki joined the U.S. Forest Service as a fisheries biologist in 1990, and advised forest management to benefit steelhead trout and salmon. That need to look both in and out of the stream would prime her for future work at Pyramid Lake.

The Lahontan National Fish Hatchery hired her two years later, assigning her to work on restoring natural connections between Pyramid Lake and the Truckee River under the 1990 Truckee-Carson-Pyramid Lake Settlement Act. The initiative spearheaded by Sen. Harry Reid aimed to resolve decades of interstate water allocation challenges while conserving wetlands and rare wildlife, namely the endangered cui-ui and the Lahontan cutthroat trout.

The fish didn’t wait long to stir things up for Heki. “I grew a lot those first couple years,” she said.

Record numbers of cui-ui showed up at a virtually defunct facility that was meant to pass them upstream from Pyramid Lake to the lower Truckee River. Heki “was pretty green,” she said, but she secured the support to fix the facility for the safety of both the fish and the staff operating it.

Her leadership told her: “Lisa, do what you need to do.”

So that’s what she did — and continues to do.

MOVING UPSTREAM WITH THE FISH

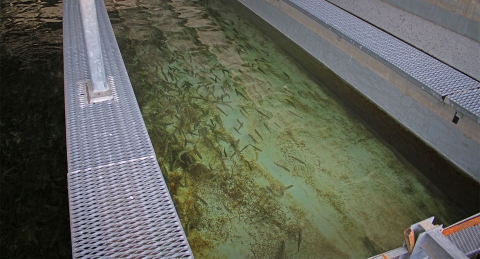

It didn’t take long after Heki joined the hatchery to start stirring things up herself. In 1995, she and then-manager Larry Marchant worked with Neilson to bring the Pilot Peak eggs from the Utah ponds to the Lahontan National Fish Hatchery to a makeshift rearing facility created in a garage.

“There was a glimmer of hope there that this may have been a remnant of that strain,” said Marchant, who has since retired. “So we did it on a shoestring budget.”

Marchant credits Heki for securing funds to later upgrade the facility for management of this strain. “She was out in front of this,” he said.

Heki fought hard to get the Lahontan cutthroat trout recovery plan, published that year, to call for investigating the potential of the lake form. The Lahontan cutthroat trout occurs in both lakes and streams, and by that point, the federally threatened species had disappeared from about 90 percent of the waters where it was found in the 19th century.

There are special characteristics about the lake form — they live longer, reach a larger size, feed on other fish, and wait a few years to start reproducing.

“We’d never seen one over 6-7 inches in the stream,” Neilson said. “When they started, they just grew fantastically. People started to get excited about them but there was still reticence about genetics.”

Heki recruited multiple experts in hopes to lay that question to rest. But it was professor Mary Peacock who started to make headway in the early 2000s. The plan was to compare the Pilot Peak strain with the original Pyramid Lake fish mounts in museums across the country.

While initial results supported their hypothesis, it took more than a decade to erase any uncertainty that the genes of the Pilot Peak fish lined up with the museum mounts. Peacock’s work was published in 2017.

“Lisa has been a champion for this fish since the very beginning, going back to 1995 or earlier,” Peacock said. “If she hadn’t been, I don’t think any of this would have happened.”

The hatchery couldn’t risk waiting for the publication. They took two leaps forward: first, they experimented with water flow to identify what regime would best maintain the habitat both in and along the water. Second, they worked with the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe to gain support to stock the Pilot Peak strain into Pyramid Lake in 2006 within the boundary of the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribal Reservation. Heki said without the tribal collaboration on stocking and evaluation, this program would not have been possible.

Neither of those steps were without extensive coordination, Heki said. She's been to her share of public meetings — in those days, often with her young son in tow. At nearly six feet tall, and wearing a federal shield, she’s wondered if that made her more relatable.

Either way, it was time to watch those fish genes play out in Pyramid Lake.

In 2014, as those first generations of trout started to reach spawning age, they headed out of the lake and into the lower Truckee — just as their ancestors did.

“It gives me goosebumps when I talk about it even now,” Heki said. “They started using the lower three miles, then the lower eight. We’re just gradually moving them upstream,” she said.

IF YOU REMOVE IT, THEY WILL COME

To the fish, that’s easier said than done. At three miles, they pass through the Marble Bluff Fish Passage Facility, the project Heki first addressed when cui-ui tried to pass in record numbers. At 10 miles upstream, they hit Numana dam. Then at 30 miles upstream, they hit Derby Dam. Providing fish passage fish passage

Fish passage is the ability of fish or other aquatic species to move freely throughout their life to find food, reproduce, and complete their natural migration cycles. Millions of barriers to fish passage across the country are fragmenting habitat and leading to species declines. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's National Fish Passage Program is working to reconnect watersheds to benefit both wildlife and people.

Learn more about fish passage over Numana Dam (an irrigation structure structure

Something temporarily or permanently constructed, built, or placed; and constructed of natural or manufactured parts including, but not limited to, a building, shed, cabin, porch, bridge, walkway, stair steps, sign, landing, platform, dock, rack, fence, telecommunication device, antennae, fish cleaning table, satellite dish/mount, or well head.

Learn more about structure within the reservation) is on track to be addressed in collaboration with the Pyramid Lake Paiute Tribe. At Derby Dam, the Bureau of Reclamation is working to fast track a fish screen on a108-year old structure and will give the trout access to 40 miles of river by 2021.

Once the trout are able to make it past Derby Dam they will be able to swim unimpeded to the California-Nevada border. The Compex is currently working with multiple partners to address fish passage barriers at four additional dams using the National Fish Passage Program funding initiative.

The Truckee River watershed will be connected from Pyramid Lake to the Tahoe Dam as early as 2022 for a barrier-free migration for these iconic trout.

“Now the story is moving upstream with the fish,” Heki said.

Tim Loux, the National Fish Passage Program coordinator for California and Nevada, likens it to the Field of Dreams, 'If you build it, they will come,' concept. Except “we’re doing it on a massive scale — 140 river miles,” he said.

As of this year, more than 900,000 Pilot Peak Lahontan cutthroat trout swim Pyramid Lake.

“This is a one-of-a-kind fish that was a threatened species and probably determined to be extinct, and now has been brought back from the brink,” Neilson said. “It’s a really neat story.”

The Lahontan National Fish Hatchery Complex staff — which went from a team of eight to now 26 people — is following the trout upstream to see how they respond to water management and how they interact with nonnative rainbow trout, with the help of U.S. Geological Survey.

Heki's vision is a spring Lahontan cutthroat festival that attracts people from across the globe, with “local communities holistically embracing this unique fishery, the Truckee River, and the economic driver it has become.”

She is sure of a future where Lahontan cutthroat trout migrate the entire Truckee.

“I expect to see them swimming through Reno and Sparks and downstream of Tahoe dam in 10 years easily, if not before,” she said.