Southern California rivers are not known for their abundance of water flow. Yet, when the rains do come, the rivers can swell in dramatic fashion.

Attempts to tame inconstant rivers have resulted in channelized, dammed or leveed waterways that resemble concrete canals more than Instagram-worthy landscapes. But one wild river remains: the Santa Clara River.

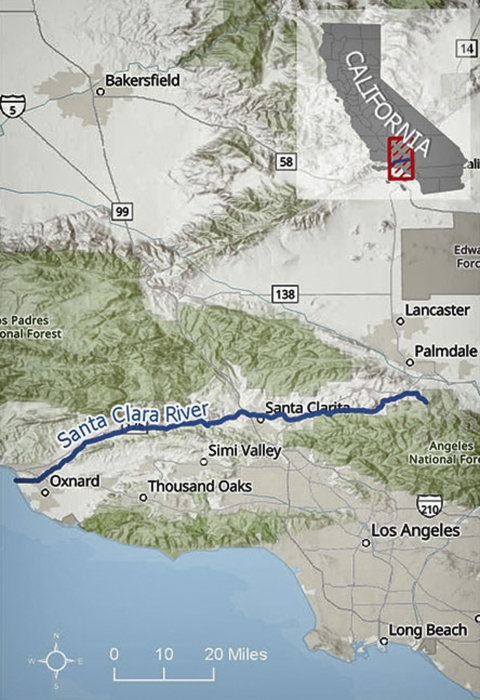

Beginning with headwaters in both the Los Padres and Angeles National Forests, the river meanders for more than 100 miles through Los Angeles and Ventura counties before flowing into the estuary on McGrath State Beach. In dry months, many areas of the Santa Clara River flow completely underground.

Despite this lack of water, much of the Santa Clara River is alive with riparian riparian

Definition of riparian habitat or riparian areas.

Learn more about riparian trees and shrubs like willows, fragrant mule fat and native pollinators like buckwheat. These provide habitat for local birds that feed on the bugs zipping through the air or crawling along the sandy river bottom.

Eleven federally listed species, and several species with dwindling population numbers, rely on the Santa Clara River as a food and habitat source.

“This includes other sensitive or listed species like the southwestern pond turtle, the unarmored threespine stickleback, and southern steelhead,” said Chris Dellith, senior fish and wildlife biologist for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Ventura. “The loss of this habitat could compromise the stability of existing populations and the ability to recover already tenuous populations of these species.”

That the Santa Clara remains relatively untouched by modern humans is due in no small part to a long-standing partnership of federal, state, local and non-governmental organizations who work to ensure it stays that way.

Spurred to action in the early ‘90s by two oil spills in the upper river, the Santa Clara River Trustee Council formed to manage $9.8 million in settlement dollars. The council funds restoration projects within the watershed to offset the damaging effects of the spills to the river and the wildlife dependent upon it.

The council, made up of representatives from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife funded the acquisition of six parcels of land along the river in Ventura and Los Angeles counties. The Nature Conservancy manages the majority of those parcels, and has also acquired additional land along the river for a total of more than 4,100 protected acres.

Much of the conservancy’s work along the river focuses on habitat restoration through invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

Learn more about invasive species removal. Preserving farmland within the floodplain is also key to maintaining the river’s wild state.

“The river’s floodplains support a great amount of agriculture. The entire Oxnard Plain was developed from deposits of sediments from the Santa Clara River over a long period of time,” said Jenny Marek, deputy field supervisor for the Service in Ventura.

E.J. Remson, senior project director for The Nature Conservancy in Ventura, remembers the day he realized that protecting local agriculture could help protect this one last wild river.

“I was actually standing on a levee and kind of marveling that we’re on the edge of one of the largest and most affluent metropolitan areas in the world, and all of the rivers in Los Angeles, Orange County and the Bay Area are all channelized concrete. So how did this river survive? I realized it survived because agriculture was still flourishing in Ventura County,” Remson said.

According to the Farm Bureau of Ventura County, the county ranked 11th in the U.S. for agriculture production.

Remson and his colleagues feared that if agriculture left Ventura County, the Santa Clara River would suffer the same fate as other Southern California rivers.

“Back in the mid-50s, Los Angeles County was the most agriculturally productive county in the country, and Orange County was number two,” Remson said. “And I said, ‘So we all know what’s going to happen if ag goes away; Ventura County is going to turn to suburban sprawl. So we thought, how do we help keep ag viable?”

That’s when the idea to protect the floodplain through easements on agricultural land was born. Together with the Ventura County Watershed Protection District and the Farm Bureau of Ventura County, The Nature Conservancy developed a concept that addressed the needs of farmers, the needs of wildlife and habitat in the river, and the need to control flooding.

With partial funding from the trustee council, The Nature Conservancy manages the Natural Floodplain Protection Program along the Santa Clara. The program offers floodplain protection easements to farmers or other landowners along the river and provides payment to the landowner in exchange for leaving their property undeveloped.

The Nature Conservancy commissioned the University of California Santa Barbara’s Bren School of Environmental Science and Management to identify which land along the river was most crucial for floodplain protection.

Armed with that data, Remson began to approach landowners.

“As a landowner, you’re always reluctant to put easements on your property. So I had to give some thought as to whether I’d be willing to do that,” said Craig Underwood, owner of Underwood Ranches and Underwood Family Farms.

He has participated in the floodplain easement program for about two years. “The program itself makes a lot of sense because if you’re going to have a river running through a valley like that and not spend a lot of money doing flood protection, you’re going to have to have some kind of a floodplain.”

The Nature Conservancy manages 551 protected acres within the river’s floodplain. And Remson says they’ve worked with a variety of agriculture land owners, from the family farm to the publicly-traded agricultural company.

“Each one is different,” said Remson. “That’s the kind of cool thing about easements -- they’re custom made. But, in general, they preserve the property and you’re encouraged to keep it in ag.”

While the land may flood during major storm events, the easement money can offset or lessen the burden of the agriculture loss. Landowners can reclaim the eroded land either by pulling it back out of the river, bringing in new topsoil, or a combination of both.

When the river is unrestricted by channelization and urban development it can expand and shrink within its floodplain as needed. This natural movement of the Santa Clara provides life for the ecosystems it supports.

Preserving the floodplain also provides an economic benefit to unincorporated Ventura County and Oxnard residents through FEMA’s Community Rating System Program. Unincorporated Ventura County currently gets a 25 percent discount and City of Oxnard residents get a 15 percent discount.

“The largest chunk of points that we get from [Ventura County's] application has to do with open space lands preserved within the floodway, and the one percent annual chance (previously known as the 100-year) floodplain,” said Angela Bonfiglio Allen, an environmental planner with the Ventura County Watershed Protection District.

Underwood recognizes the value of allowing the river to flow naturally, uninhibited by human interference. Just for slightly different reasons.

“E.J. [Remson] and I don’t always see eye-to-eye on The Nature Conservancy goals, but in this case I think [The Nature Conservancy’s] program is a good one because if you were to channelize the river and not have floodplains, based on their projections, then it would cause a lot more damage when you get into the urbanized areas,” said Underwood.