Pepper Trail’s name is as unique as his job with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Clark R. Bavin National Fish and Wildlife Forensics Laboratory in Ashland, Oregon. As a forensic ornithologist for the last 20 years, Trail has been successful at solving hundreds of crimes involving birds from around the world, often one feather, beak, bone or talon at a time.

“I have a strange job - I identify the victims of wildlife crime when the victim is a bird,” said Trail. “I’m one of only two people in the world who do this.”

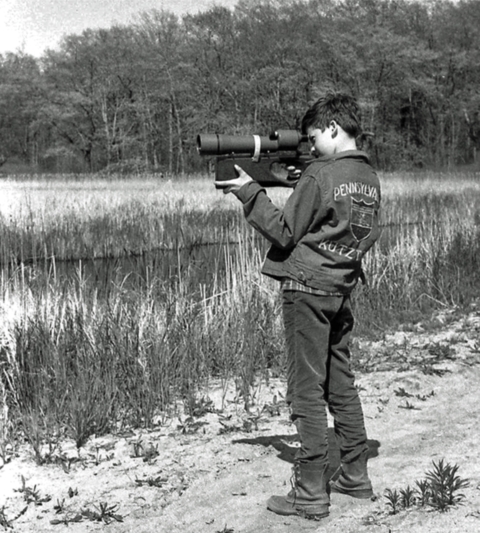

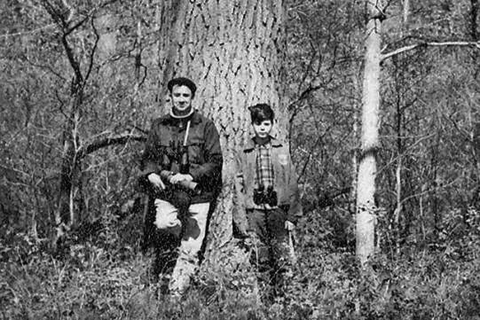

Trail’s interest in birds began while growing up in New York. His dad was a professional photographer and introduced Trail to the outdoors. By the age of 10, Trail had started his birdwatching life list. His childhood interests led to an education in the sciences culminating with a Ph.D. in ornithology from Cornell University. Trail jokes that he’s a legitimate Dr. Pepper.

For his doctoral research, Trail lived in Suriname, South America studying the mating habits of the Guianan Cock-of-the-Rock, a brilliant orange bird the size of a large pigeon.

“It was a good choice for me but it wasn’t without challenges,” Trail said. “My research station was nothing more than a thatched roof hut, with a hammock to sleep in and kerosene for cooking and light.”

After a two year research project in American Samoa, Trail was content to find work as a contract biologist and volunteer in Ashland after moving there for his wife Debra’s medical career.

He was given a tour of the forensics lab, but never imagined he’d end up working there. However, in 1998 the forensic ornithologist position unexpectedly opened up, and Trail was in the right place at the right time.

“It was a steep learning curve; most of my working life had been in the field so it was a little intimidating when I walked into a lab with a huge backlog of court cases,” Trail said. “I wasn’t sure about the law enforcement aspect, or if there would be enough variety for me. I didn’t want an unchallenging desk job.” He didn’t need to worry.

One of Trail’s first cases required him to identify thousands of feathers from different birds of prey.

He scoured reference specimens and studied the most minor physical differences for clues. Having an eye for detail helped too.

“I learned very quickly about eagles and hawks,” Trail said. “The case allowed me to focus on the small variations between the species.” Today he can tell one raptor feather from another with a glance.

Technically, Trail is a morphologist, meaning he identifies birds by studying the shape and anatomy of their remains, often in varying stages of decay. At his disposal are over 11,000 individual specimens from 1,600 species of birds preserved in the lab’s extensive – and indispensable - reference collection.

As is the case with all forensic evidence, Trail’s conclusions need to hold up in court. He has to be able to prove beyond a reasonable doubt that his identifications are solid. Since that first raptor case, Trail has assisted with hundreds of law enforcement investigations for state and federal agencies, and international governments.

Songbirds and raptors make up more than half his case load. Trail figures he has identified over 800 bird species in evidence submitted to the lab. His casework includes the possession and sale of feathers of protected species, bird trapping, shooting, poisoning and even the smuggling of live birds.

And just when he thinks he’s seen it all, something new comes across the exam table.

One of the strangest was in a takeout food container from New England. Inside was a small piece of cooked, seasoned meat with garnish on toast. Trail’s first thought was “how kind, someone sent me dinner.”

Instead it was evidence in a suspected crime. Federal agents received a tip about an east coast restaurant serving wild woodcock. These forest-dwelling sandpipers are legal to hunt, but the commercial sale of their meat is illegal. The agents ordered woodcock from the menu and asked for one to go, which they sent to Ashland. Based on Trail’s identification of the breastbone, the restaurant was raided and dozens of frozen woodcock were confiscated and sent to the lab.

“Our de-fleshing dermestid beetle colony feasted on those, cleaning the bones,” said Trail. “It was probably a nice change of pace from their usual diet of rotting roadkill.”

One would assume that after a career handling dead animals there would be a certain amount of despair about the state of wildlife. Trail said it happens.

“There are times when my colleagues and I wonder how is anything even alive out there?” said Trail. “So I take every opportunity to observe living birds, either locally or as the expert naturalist for birding tours. I try to do one or two trips a year to keep my sanity.”

Also keeping him sane and productive is the Feather Atlas, which Trail calls one of his personal accomplishments. He created the online searchable database to help Federal agents quickly identify feathers to support their law enforcement actions.

Today, the atlas has grown to 400 species represented by nearly 1,800 scanned images of flight feathers from North American birds. The site has been discovered by birders and artists as well as scientists and law enforcement, and is now attracting over 1.5 million visits a year.

Then there are those items which Trail handles that tug at his gentle soul. Many birds are illegally killed for decorations, talismans, accessories and traditional medicines to be sold on the black market in the U.S. and abroad. One such item arrived in 2013.

A box containing dozens of small red paper tubes wrapped in satin tassels was sent to the lab. Inside each tube was a dead, dried hummingbird and a Spanish-language prayer. They were Mexican love charms, or chuparosas, believed to help one find true love.

The illegal trade of chuparosas and the number of hummingbirds killed each year to produce them is significant. To date, Trail has processed over 800 confiscated charms and identified at least 18 species of hummingbirds used in their production, many of which occur in the U.S.

“I worry the chuparosa market is growing, becoming more commercialized, since many have ‘made in Mexico’ stickers on them,” Trail said. “The chuparosa is one of those illegal trade issues that may not be resolved before I retire.”

Retire is exactly what Trail hopes to do in the coming year. While leaving the lab will be bittersweet, he has no shortage of interests to keep him busy. He is an accomplished poet and published author, and has been known to channel his inner explorer by performing in the persona of Charles Darwin for local clubs and events.

While Trail’s absence will leave a void in the lab, he has taken Ariel Gaffney, the lab’s newest ornithologist, under his metaphorical wing since 2017 to mentor and pass on his years of avian wisdom and experience.

“I have so much respect for Pepper’s knowledge and skill, and feel privileged that he shares that with me,” said Gaffney. “The more I work with him, the more he has become the most influential biologist in my life. I am profoundly grateful Pepper is my mentor.” Morphology department supervisor Barry Baker said that Trail’s uncompromising ethics, passion for wilderness and dedication to excellence in science will continue to be a great influence on others.

“Pepper sets the example by his actions, how he lives his life and approaches his work,” said Baker. “For me, Pepper’s work constantly reminds me that anyone can ‘do the right thing’, and lives up to the belief that we are often most effective by thinking globally and acting locally.”