Imagine one moment you’re basking on a log on a warm day in early summer, soaking in the sun after foraging in a cool, spring-fed wetland. The next, you’ve been thrust inside a bag, wondering if you’ll ever see the marsh you call home again.

Most turtles collected illegally from the wild don’t.

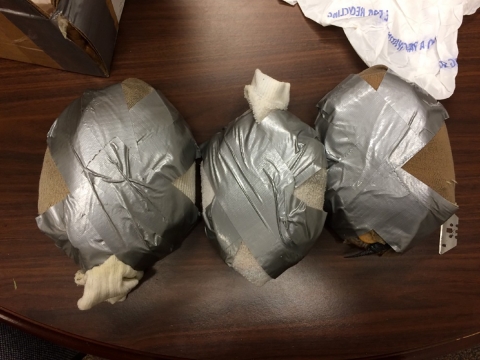

Law enforcement officials have reported an increase in the trafficking of native turtles in the United States, from common species like the Eastern box turtle to federally listed species like the threatened bog turtle. Most are exported to Asia, but many are sold right here in the U.S., sometimes falsely advertised as “captive-bred” pets.

Poaching usually ends a turtle’s natural life, even if it is seized from traffickers alive.

“As of now, most turtles confiscated cannot be released back to the wild,” said Noelle Rayman-Metcalf, an endangered species biologist based at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s New York Field Office. “There’s no way to know exactly where they were taken from, and releasing them just anywhere within their range could have unintended genetic consequences for populations that have adapted to survive in certain areas over generations.”

Releasing confiscated turtles also risks introducing novel diseases contracted due to unsanitary conditions, or exposure to other animals. That means most seized turtles will end up living out their long lives in captivity, in conditions that don’t come close to their native habitat. Imagine going from a five-acre wetland to a five-gallon tank.

Motivated by the urgency of the turtle-trafficking crisis, scientists are working to address long-standing barriers to repatriation by developing genetic databases to narrow down where turtles were taken from, and disease-screening protocols to mitigate the risks of releasing them.

While returning healthy turtles to the wild, if possible, is a top priority, developing a process for how best to do so safely will take time. For now, the reality remains: those in captivity may never go home, and the loss of those individuals has serious consequences for the populations they leave behind.

“When you take out any adults, especially females, you may have just created a functionally extinct population,” Rayman-Metcalf said. “It can be devastating.”

Biologically, turtles are more vulnerable to illegal collection than other taxa: adult turtles must reproduce for their entire lives to ensure just one hatchling survives. And it takes years, often decades, for turtles just to reach reproductive age, if they make it at all. Most fall victim to predators before they mature. Others fall victim to habitat loss and car strikes when crossing roads.

When people take individual turtles, they wipe out future generations.

Some people take hundreds.

Illegal collection subtracts an unknown number of turtles from wild populations that are already stressed. It undermines biologists’ ability to study and recover vulnerable species, and to keep common species common. “It’s a threat we cannot easily see,” Rayman-Metcalf said.

Not a new problem, within or beyond our borders

The recent spike in the illegal collection of native turtles in the United States poses a serious threat to species that are already at risk, such as the spotted turtle, wood turtle, bog turtle and alligator snapping turtle.

But the demand for North American turtles is not new. In the late 19th and early 20th century, diamond-backed terrapins were considered a culinary delicacy. Alligator snappers were heavily traded in the 1960s, 70s, and 80s. Both eastern and western box turtles have been common in the pet trade since the 1990s, and wood and painted turtles have become increasingly popular as well.

The trends in the United States reflect, and feed into, a global wildlife-trafficking problem. Turtles are taken to meet domestic and international demand, often in spite of regulatory barriers. Wood turtles, for instance, appear to be a prime target of poaching, despite being protected in every U.S. state and listed under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) Appendix II — which regulates trade to prevent exploitation.

Alarmed by the growing threat to turtle species that are already in trouble, scientists and law enforcement professionals are working together to establish multi-agency partnerships, identify information gaps and scientific needs, and align resources to meet them.

Here are some of the initiatives underway to help combat the trafficking threat, and offset damage to wild populations:

- Keeping turtles SAFE — The Association of Zoos and Aquariums launched a new American Turtles Program as part of its Saving Animals from Extinction (SAFE) initiative to help coordinate efforts to ensure confiscated turtles are housed and cared for, freeing up law enforcement agencies to concentrate on apprehending traffickers.

- Shell game planning — Service staff are developing a workflow from point of confiscation to final outcome for species, including protocols for health screening, based on input from the Northeast Wildlife Disease Cooperative.

- Casting a net(work) for turtles — The Partners in Amphibian and Reptile Conservation have formed a Turtle Network Team to help cultivate partnerships and foster communication and coordination for North American turtle conservation.

- 23 and Me, for turtles — Partnering conservation genetics laboratories are developing DNA libraries for wood, spotted, Blanding’s, and bog turtles that will help biologists determine where seized turtles came from, in hopes of being able to return them home.

- Social cues and clues — Social scientists with the Service’s Human Dimensions Branch are researching the drivers of demand for native turtles to help figure out the best strategies for reducing demand, or redirecting to legal alternatives.

Turtle power

Native turtles are national treasures. The U.S. encompasses a globally significant biodiversity of wild turtles. According to some assessments, our country is home to the greatest total number of turtle species and subspecies of any single nation, and the greatest number of endemic species — those that only live here. Of the 57 known native species of turtles and tortoises in the U.S., more than 40 percent are at risk of extinction. Globally, more than 60 percent of turtle and tortoise species are at risk.

Southeast Asia was once home to a globally significant diversity of turtles too. As of 2010, it had the highest total threat levels for turtle taxa. That’s why turtles in the U.S. are increasingly targeted. Wildlife trafficking is a multi-billion dollar global industry that exploits the natural diversity intrinsic to global ecological niches. Just as the demand for exotic wildlife products in the U.S. has led to exploitation of species abroad, the demand for turtles here and in other parts of the world has put our turtles at risk.

Here are some things you can do to help protect native turtles:

- Report suspicious behavior. If you suspect someone is collecting or selling wild turtles, call our tip line (1–844-FWS-TIPS) or your state wildlife agency. The Service may pay rewards for information or assistance related to investigations. Learn More

- Know the laws. The illegal collection and sale of wildlife may violate state, federal, and international regulations, including the Lacey Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

- If it’s safe to do so, help turtles cross the road. Escort turtles across the road in the direction they are already heading. Don’t ever move a turtle to a different location. You may think there is an ideal wetland somewhere else, but the turtle is better off in the habitat where it has grown up with all of the friends (and enemies) with which it’s familiar.

- Before you buy, do your homework. Pet turtles require specialized care for decades, so be sure you are ready for the commitment. If you are, be a cautious consumer. Ask for certification that the turtle was captive bred. Or better yet, adopt an unwanted pet from a shelter. If you purchase an adult, examine it carefully. The shells of wild turtles will look a little weathered — they might even be marked by biologists for populations surveys.

- Don’t release pets. If you are no longer able to care for a pet turtle, don’t release it into the wild. It could transmit harmful diseases to wild populations. Bring your pet turtle to an animal shelter.

- Be a good turtle neighbor. Learn what species are native to your community. Visit national wildlife refuges, zoos, or nature centers to find out about local turtle conservation efforts. There may be opportunities to volunteer.

This blog was written in collaboration with Jenell Walsh-Thomas, an American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) Science & Technology Policy Fellow with the Combating Wildlife Trafficking Strategy and Partnerships Branch of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s International Affairs Program.