Collier County is one of Florida’s greenest with two-thirds of its lands set aside for conservation. Large swaths of territory – Florida Panther National Wildlife Refuge, Big Cypress National Preserve, Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary – will never be developed while providing a safe haven for all manner of wildlife.

What makes Collier special also makes it popular. Its population is expected to rise 50 percent over the next quarter-century. With so much land already protected, where will the new homes and businesses go? Hemmed in by refuges and preserves, and the Gulf of Mexico, the only area open to growth and development is northeast Collier.

A dispute, though, has developed between preservationists, worried about sprawl and threats to wildlife, and landowners who insist any new development will be environmentally friendly with plenty of protected land and corridors for wildlife. Of concern to both factions: What will more homes and roads mean for the Florida panther and other threatened and endangered species?

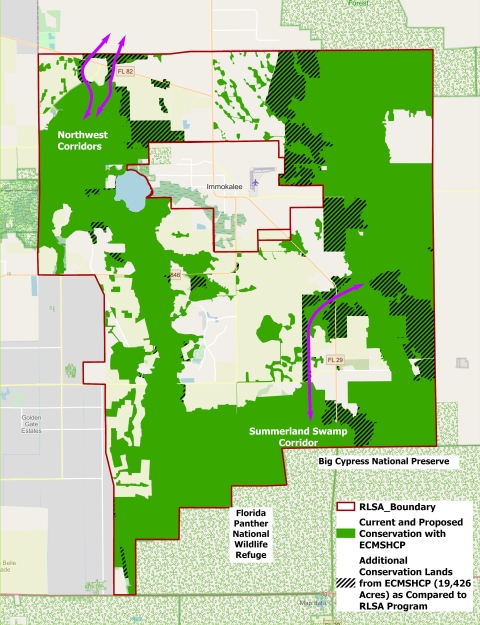

A proposed 150,000-acre “habitat conservation plan” for northeast Collier County would consolidate residential and commercial properties onto lands deemed less valuable for wildlife. Fully 70 percent of the area would remain largely unchanged, a mixture of ranchland, farm land, and native habitat for the benefit of the panther and other animals.

“We are the nation’s wildlife conservation agency and, in close cooperation with our many public and private partners, we will continue to seek the right balance between our mandate and the needs of the local community,” said Larry Williams, the Ecological Services supervisor in Florida for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service). The Service is currently reviewing the conservation plan.

“Whatever the plan’s outcome, we will mitigate the impact to our trust species while ensuring that the environment will be protected and the local economy will thrive.”

Great opportunity

The Service offers private landowners, as part of the Endangered Species Act, regulatory approval for development actions. Landowners, though, must first craft a conservation plan to protect the habitat that the species depend upon for survival and, ultimately, recovery.

A dozen landowners in Collier County have put together a conservation plan. The land currently is zoned to allow one home every five acres, a patchwork development pattern that invariably leads to more conflict between residents and wildlife.

Interactions between humans and panthers, including the loss of pets and livestock, will likely increase as development pushes farther into south and central Florida. And they’ll only get worse if the inevitable demand for more housing in Collier County is answered with more sprawling, ranchette communities that are permitted under the current zoning. The conservation plan is intended to keep panthers and humans as far apart as possible by clustering the homes and shops away from panther habitat and corridors and by creating natural buffers, like waterways, between people and panthers.

A key component of the proposed plan is the establishment of a conservation trust fund financed by fees on property sales within the project area. It’s expected to generate $150 million over 50 years to buy more land and enhance wildlife corridors.

If approved, the east Collier project would rank as one of the largest private conservation plans east of the Mississippi River.

“Working on this plan is a great opportunity to make sure new development doesn’t lead to the loss of important habitat, and to set an example for other landowners throughout the Southeast,” said Elizabeth Fleming, a senior Florida representative with the conservation nonprofit Defenders of Wildlife. “If we do this correctly, we can do more than make development in this area less of a threat to our imperiled species. We may even be able to open up new opportunities to help them thrive.”

Other conservation groups, including the Florida Wildlife Federation and Audubon Florida, support the plan. Others don’t. The Conservancy of Southwest Florida, for example, says the plan might sever the corridors panthers use to reach the Caloosahatchee River and northern protected lands. Critics also say more roads and cars will translate into many more panther deaths. Twenty panthers died last year in collisions with vehicles; 23 died the same way the year before.

Accurately evaluating, predicting, and attributing any increase in roadway mortality is in much dispute. Concerted efforts, though, are being made to mitigate any harm to any animal. The $150 million Marinelli Fund, for example, will be used for a slew of wildlife crossings, including bridges, specially designed culverts and fencing to keep panthers and other wildlife from entering roadways.

Exceedingly careful

The “recovery” of a species, especially a predator like a panther, is a delicate, decades-long dance that balances the health of the animal with the needs of the community. In 1995, for example, maybe 30 panthers, all suffering genetic defects from inbreeding, prowled the swamps and forests of southwest Florida. The Service, along with the state of Florida and other partners, captured eight healthy, female panthers from Texas and set them loose in Florida to breed. Today, anywhere from 120 to 230 panthers roam Collier and adjoining counties.

Any proposed change to an endangered species habitat prompts a comprehensive biological analyses. The east Collier habitat plan itself is 376 pages. Discussions with landowners began a decade ago. The review process is time-consuming and, for a resource-strapped agency like the Service, costly.

Nationwide, federal agencies occasionally accept private dollars to offset the cost of reviewing a particularly large permit application. The money must be used in a way that maintains the agency’s independence and objectivity while avoiding any conflict of interest.

The Service received $287,000, over six years, from the Collier County landowners requesting the habitat conservation plan and permit. The Service used that money to hire biologists who worked on projects other than the large scale habitat conservation plan. In effect, the Service created a firewall between the Collier County landowners and the permit they sought. This arrangement allowed senior and experienced biologists to undertake the difficult analyses needed for the habitat conservation plan, while also allowing other biologists to tackle the more routine permit applications without delay.

“We have been exceedingly careful to not use any money from landowners to review the habitat conservation plan,” Williams said. “And no employee with decision-making authority was paid with private dollars. Nobody tells us how to do our jobs.”

Service biologists are currently scrutinizing the east Collier project to ensure, if approved, that none of the threatened or endangered species, or their habitats, would be jeopardized. A final environmental impact statement, that incorporates public input, should also be completed by year’s end. Each report will ultimately determine if – and how – development can co-exist with the recovery of an iconic species.

“Virtually everybody agrees that you can’t do conservation work in the South without private landowners who own most of the region’s land,” said Williams. “So, in the interest of conservation, we will collaborate with others who share our concern for the future of Florida panthers and other species. But in the end, we won’t approve a habitat conservation plan unless we are certain that it safeguards the species.”