On a spring night in 2007, Kurt Buhlmann sat on an overturned five-gallon bucket with a headlamp and a pair of binoculars, looking for wood turtles emerging from a streambank and clambering toward an adjacent farm field to nest.

When he spied one of the rare reptiles, he would intercept it, carry it to the other side of a stream — onto Great Swamp National Wildlife Refuge property — and place it on a low mound of dirt he and refuge staff had built up as an alternative nesting area.

“The turtles would check it out, and then wander off,” Buhlmann remembered. “But the next night, one of the females came back and made a nest.”

A step in the right direction.

Buhlmann, a research scientist at the University of Georgia’s Savannah River Ecology Laboratory, has devoted his entire career to turtle conservation. But he said over time, “It’s really morphed into species recovery.” Not just conserving healthy turtle populations from encroaching threats, but bringing back those already on the brink.

The wood turtles at New Jersey’s Great Swamp, part of the Lenape National Wildlife Refuge Complex, illustrate both the potential for recovery where suitable habitat still exists — or can be created — and the collaboration it takes to succeed in the face of complex challenges. Including finding isolated, or relict, populations before they fade away.

Disappearing act

The wood turtle is neither strictly aquatic nor terrestrial: it lives both on land and in water. This duality has made it vulnerable to the loss of either aquatic or terrestrial habitats in New Jersey, where its native range — in the northern part of the state — lies within commuting distance of New York City. By the 1970s, much of its habitat had been lost or degraded by development, fragmentation, and pollution.

In 1979, the wood turtle was listed as a State-threatened species in New Jersey. In 1992, the state’s Natural Heritage Program described the species as seemingly secure globally and yet “rare in New Jersey.”

It was around that time that a wood turtle was last seen at Great Swamp.

More than a decade later, Buhlmann received a grant to support habitat-improvement projects for rare turtles at several national wildlife refuges around the country — including Great Swamp. While Buhlmann was working with biological technician Colin Osborn on surveys there for another turtle species, refuge biologist Mike Horne suggested they start by looking in a stream on the edge of the refuge.

“Colin and I headed right over, waded in, and found an old female wood turtle,” Buhlmann said. They put a radio transmitter on her, tracked her for several weeks, and she led them to the farm field — where she nested — and to another old female who was nesting there too.

Shortly afterward, refuge neighbor Tim heard a knock on his door. “Kurt introduced himself, and explained they were tracking some turtles, that had wandered off of the refuge” he said. Tim and his wife Marsha own nearby Turtle Brook Farm, which contains habitat suitable for wood turtles.

“We’re happy the refuge is there — it’s part of the reason we bought this property — so we wanted to do whatever we could do to contribute,” Tim said.

The scientists found several more turtles that year — both males and females — and several nests, which they covered with cages to protect the eggs from predators like raccoons.

Because the habitat in the farm field was limited — just a small opening that was succumbing to invasive plants — Osborn, Horne, and Buhlmann also built up nesting habitat on the other side of the stream (the aforementioned dirt mound) with help from the refuge’s engineering equipment operator Dave Miller, and began helping females “find” their way over to it.

“We had a good routine,” Buhlmann said. “For several years, I would spend a couple of weeks at Great Swamp during nesting season in the midst of traveling to other sites, tracking females and protecting nests.” He would return in early September to collect hatchlings as they emerged, marking them and then letting them loose to disperse to the stream.

But there was a problem. “We weren’t seeing the hatchlings in successive years,” he said, adding, “Which isn’t a surprise.”

Most hatchling turtles don’t survive to adulthood simply because they are so small at birth, making them easy targets for a whole suite of predators. They are bite-size snacks.

Adding to the challenge: female wood turtles don’t reach reproductive age until they are about 14 years old, so they often must reproduce for their entire adult lives, many decades, to ensure one of their offspring survives to replace them in the population.

“If you are trying to recover a turtle population, half the problem is that their life history is like that of humans: it takes so long to reach maturity,” Buhlmann said.

So while it wasn’t surprising that they weren’t finding hatchlings, it was disconcerting. With just a handful of old females left, the prospect for recruiting new turtles into the population was increasingly small.

Out of the woods

In the fall of 2010, Brian Bastarache got a call from the woods. It was Buhlmann. “He said, ‘I’m at Great Swamp and we’re having dismal success with our direct-release hatchlings. We want to send them to you guys.’ ”

Bastarache, the Natural Resource Management Department Chair at Bristol County Agricultural High School in Massachusetts — known as Bristol Aggie — had been working with Buhlmann and his wife Tracey Tuberville, who is also a research scientist at the Savannah River Ecology Lab, on a project to recover Blanding’s turtles at Assabet River National Wildlife Refuge.

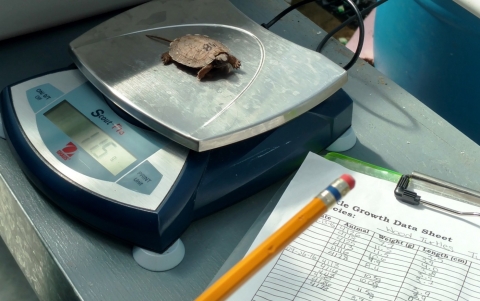

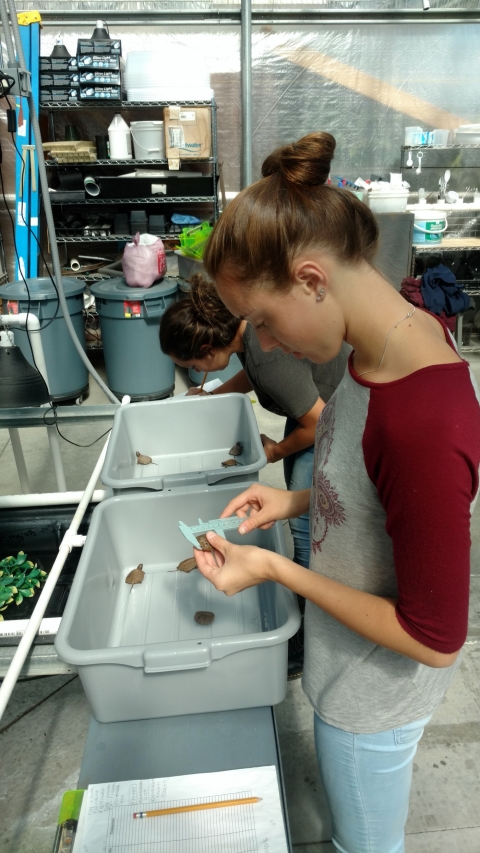

Bristol Aggie played a key role in the effort by providing a secure facility and personnel to support head-starting, a conservation technique in which hatchling turtles are temporarily removed from the wild at the time when they are most vulnerable to predation, in hopes of giving them a better chance of survival when released months later, bigger and stronger. It has proven to be effective.

Jared Green, who now coordinates the turtle work at Great Swamp, worked as a biological technician on the Blanding’s turtle project at Assabet River and then pursued his master’s degree working in Tuberville’s lab. For his thesis research, he studied the effectiveness of head-starting as a management tool for the species, and found that the apparent survival of head-starts in the first year after release was nearly six times higher than turtles from the same population that were not head-started.

It was just the kind of boost the wood turtles needed. With permits from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and New Jersey Division of Wildlife to transport turtles across state lines, Buhlmann brought the first cohort of hatchling wood turtles to Massachusetts in 2011.

But they needed more than permits to succeed in the long-run. They needed funding to support field work and equipment.

For the Friends of Great Swamp, it was an opportunity to step up. Every fall, the Friends have a joint-planning meeting with the refuge to talk about needs and priorities — at the 2010 meeting, turtles were at the top of the list. In their subsequent board meeting, the Friends decided to fund the wood turtle project.

“We’ve supported the project in a few different ways since then: not only funding Kurt’s research, but also buying radio transmitters to track the turtles,” explained Laurel Gould, Treasurer of the Friends.

For several years, they also funded summer interns who helped support a variety of needs, including outreach to the public. Head-start turtles are now the main draw at refuge events in the spring and fall.

“Back when we started, ‘head start’ was not a common term in the wildlife field. I think a lot of credit goes to the work here at Great Swamp to advance this approach,” Gould said. “We’re so pleased to be involved.”

Second chance

More than 200 wood turtles have been now been released at Great Swamp after spending winters at Bristol Aggie. About a quarter of them are outfitted with transmitters so researchers can track their progress. So how are they doing?

This spring, the team — Buhlmann, along with refuge volunteer Jim Angley, Osborn, Green, and others — captured 30 head-started turtles. “Some that we have never seen since we released them,” he said. They found representatives from eight of the nine years that the program has been taking place.

Not only do more survive — an estimated 48 percent, compared to about 13 percent among turtles that have not been head-started — they have physiological advantages too.

After nine months at Bristol Aggie, where the hatchlings eat all winter instead of hibernating like they would in the wild, the wood turtles grow to the size of three- or four-year olds. While they don’t continue to grow at that rate once they are released in the wild, that head start on development may lead the turtles to reach sexual maturity earlier.

By any measure, the project is a success, made possible and driven by partnerships.

More than 10 years after opening their door to Buhlmann, refuge neighbors Tim and Marsha continue to engage with the scientists in discussions about land-management opportunities that will help improve habitat for wood turtles. Their openness to modifications that will help reduce risks to the turtles — like waiting to mow fields when the turtles are less likely to be clambering through them — speaks to their personal connection to the project, and their belief in its value.

In addition to helping with ongoing habitat management needs on the refuge, Miller, the engineering equipment operator, gives up some of his office space every fall when the field technicians are collecting hatchings to send to Bristol Aggie. There is a full bathroom adjacent to his office, and Miller said, “I’ll open the door, and the tub will be full of hatchlings.”

The natural resource management students at Bristol Aggie, who receive training at the beginning of each school year in biosecurity protocols and best practices for wildlife care, are so invested in their charges that when the covid-19 pandemic hit, Bastarache and his colleague Kourtnie Bouley received frantic emails from students asking who would look after the turtles.

“Working on something that’s bigger than them gives them purpose,” Bouley said. “They realize: This is a job I could potentially do when I leave here.”

She is a case in point. A former student at Bristol Aggie, Bouley helped head-start turtles and worked as an intern at Assabet River.

The Friends of Great Swamp continue to provide funding for the project, and to celebrate its success through events and newsletter articles.

Wood turtles everywhere need people working together to look out for them, and in our region, partners are leading by example. In early 2021, the Northeast states received a nearly $1 million Competitive State Wildlife Grant to continue years of scientific collaboration to address the range-wide decline of the species — the grant includes funding for Bristol Aggie to care for wood turtles confiscated by law enforcement officials. That’s because while habitat loss and fragmentation remain a problem, the biggest threat to this and other turtle species is one that’s harder to see.

Around the time the last wood turtle was documented at Great Swamp in the 1990s, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service determined that the species did not warrant federal protection. But the authors of the finding added an important caveat, describing the wood turtle as a species that “although not necessarily now threatened with extinction may become so unless trade in them is strictly controlled.”

The illegal collection and trade in turtles is a growing problem in the U.S. For a small, isolated, aging population like the one at Great Swamp, poaching would have meant the end.

Fortunately, partners got there first. Instead of disappearing, the turtles got a second chance.