For environmental advocate Florence LaRiviere, it all started at a worn-down picnic table.

It was 1951 in Palo Alto, California. The nurse and her husband, Philip, a Navy navigator and physicist, had just moved into an affordable post-war home. To escape the heat, the young couple would pack up their children and dinner, and ride a few miles over to the breezy edge of the San Francisco Bay.

“I will tell you there is nothing so lovely, no place so charming, as the marsh in the evening. The tide changes and moves the cordgrass. It bends back and forth…the only sound – it can be very quiet – is the birds jumping into the air and crying as they fly,” said Florence LaRiviere, who is now 95.

LaRiviere and her husband would spend the next half-century ensuring future generations could play in the pickleweed at the end of the road. That – and more. Indeed, in extension of their efforts, most of the bay south of the San Mateo Bridge is in public ownership. At the center of that labor of love, still today, is LaRiviere.

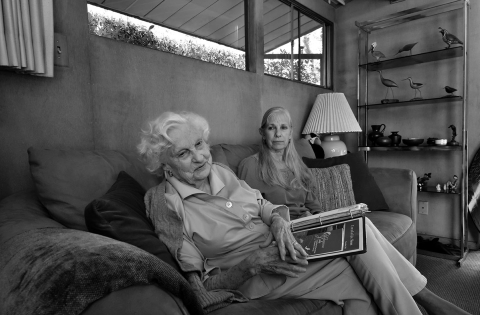

Measuring under five feet tall, LaRiviere has a wispy voice and a demeanor of both grit and grace. She rattles off years and names and organizations with little more than a brief pause. She is now legally blind, and calls her glasses “just protection from flying objects.”

Dredging first caught her attention in the 1950s. From their treasured picnicking spot, the LaRivieres noticed that the city was “scooping out a bucket of mud from the bottom of the bay, swinging the arm around and dropping all that mud on live, beautiful tidal marsh” to maintain the harbor, she said. “And we knew something was wrong there.”

Not only that, but developers were floating a $30-million plan to transform the marsh. LaRiviere poked around and discovered the local Audubon chapter. “It was a bunch of women that would go to the council meetings, planning committee meetings, and make a scene about what they saw happening that shouldn’t be,” she said.

Audubon members Lucy Evans and Harriet Mundy took LaRiviere under their wing. It didn’t matter that LaRiviere didn’t know one bird from another. She’d found her calling.

She was shy, but “if you get fussed enough, you will stand up and say something,” she said.

LaRiviere said Evans and Mundy were nurturing, but also fed her challenges. “To the extent that sometimes they’d call me up and say, ‘You go down here and here’s what I need you to say,’” she said, laughing. More than one person has said the same about LaRiviere – when she calls, you go.

Their first shared victory came in the early 1960s when their petition stopped potential development until creation of a land-use plan. That Palo Alto marsh later became the 1,940-acre Baylands Nature Preserve, managed by the city on the southwest side of the San Francisco Bay.

As LaRiviere said, it was just the first time that she’d get her feet “wet in the wetlands.” “The bay was a constant source of destruction,” she said. “That’s how we started really getting worried about everything going on along the edges of the bay.”

Even then, LaRiviere saw clues to the great natural history of the bay. She envisioned flocks like a dense cloud that darkened the sky, grizzly bears along the banks of streams, and giant condors hovering in the sky.

These wildlife wonders are captured in Malcolm Margolin’s “The Ohlone Way,” which describes the San Francisco region prior to European arrival.

“That story kept me inspired to keep fighting,” LaRiviere said.

Scientists estimate that the bay was then chock full of cordgrass, pickleweed and saltgrass across its nearly 200,000 acres of tidal marsh. Following the 1849 Gold Rush, it shrank, as marshes were diked and drained for farming or evaporating salt, or filled for development. Hydraulic mining in the Sierra foothills sent contaminated sediment flowing downriver to the bay.

As the marsh withered to 40,000 acres, so too disappeared the grizzly and the condor. Researchers have called it the most invaded, most altered estuary in the world. Just over 100 years after the Gold Rush, the demand for houses and business threatened to take the rest.

While three women – Sylvia McLaughlin, Kay Kerr and Esther Gulick – took up the charge in the Berkeley area, creating the association now called Save The Bay, LaRiviere was becoming the center of a network that would establish the nation’s first urban national wildlife refuge national wildlife refuge

A national wildlife refuge is typically a contiguous area of land and water managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for the conservation and, where appropriate, restoration of fish, wildlife and plant resources and their habitats for the benefit of present and future generations of Americans.

Learn more about national wildlife refuge – right along the eastern fringe of the bay.

This chapter started in 1965, not at a picnic table but at LaRiviere’s kitchen table, where she read the local newspaper. In it was an invitation: ‘If you’re worried about what’s happening to the shores of the San Francisco Bay, come to my office in the morning at 10 o’clock,’” she recalled.

She, and a couple dozen others, showed up at the office of Santa Clara County planner Art Ogilvie. He wanted Congress to establish a national wildlife refuge in the bay, “Then we will have the federal government to preserve our precious wildlife and our marshes,” said LaRiviere, quoting Ogilvie.

“That was the beginning of a long, long journey that persists to this day,” she said.

Out of that gathering grew a grassroots committee that met with garden clubs, environmental groups, agencies, women’s clubs, fraternal clubs – you name it.

“We would speak anywhere anyone would have us,” LaRiviere said. San Jose State University professors would wait as late as midnight to speak at these meetings, to preach the value of the marshes to the surrounding communities. Their success, according to LaRiviere, would rely on knowledge and attitude.

“You have to know your own subject,” she said. “Almost always, you need to have a good hands-on, feet-on understanding of the land you’re talking about and why it’s of value.” And, of course, be cheerful, she said.

It worked. Three years later, the committee approached U.S. Rep. Don Edwards with the request to establish the national wildlife refuge. In 1972, his bill passed and was signed by President Richard Nixon.

The San Francisco National Wildlife Refuge, later renamed to honor the Congressman, would soon stretch 180,000 acres from Dumbarton Bridge south to Alviso.

“With the kind of government we have, you can be effective,” LaRiviere said. “We dusted off our hands, and we said, whoa, we did it!”

In 1985, LaRiviere brought people around that same kitchen table. They felt they’d made a big mistake, she said. “We were not ambitious enough.”

The group had focused on protecting and restoring salt evaporation ponds, but they now saw development encroaching the neighboring areas, the seasonal wetlands. Together, the marshes and wetlands are home to more than 750 wildlife and plant species, including shorebirds, ducks, and the endangered salt marsh salt marsh

Salt marshes are found in tidal areas near the coast, where freshwater mixes with saltwater.

Learn more about salt marsh harvest mouse and Ridgway’s clapper rail.

The Citizens’ Committee to Complete the Refuge was born. The all-volunteer organization that meets monthly to this day. Their near-term goal was to expand the refuge boundary, but they remain in pursuit of restoring and protecting every open acre of bay shoreline and salt pond.

“We started standing on levees of the bay with a clipboard and a petition saying ‘I really like this land on the edges of the bay and I’d like to keep it from development. Sign me on.’ And we got thousands of signatures that way,” she said.

They developed brochures and pamphlets. Safeway even printed their material on paper grocery bags.

“Then it was about time, and we went to Mr. Edwards again,” LaRiviere said.

The committee had secured permission to protect more land, but “then there’s the battle to keep the lands from being destroyed before they can be purchased,” LaRiviere said.

One of those battles had long been underway – around yet another table, in the home of Ralph and Carolyn Nobles. The Nobles and their organization, the Friends of Redwood City, had defeated a Mobile Oil plan to develop the 3,000-acre Bair Island along the bay.

But the island was still at risk, LaRiviere said. The bay’s environmental groups once again joined forces. The committee and Friends of Redwood City recruited bay Audubon chapters – spurred by Arthur Feinstein – and enlisted the help of Sacramento consultant Bill Rukeyser to convince Japanese developer Kumagai Gumi to sell the island.

Rukeyser was advised to get the owner’s name “out in public” with his photo, LaRiviere said.

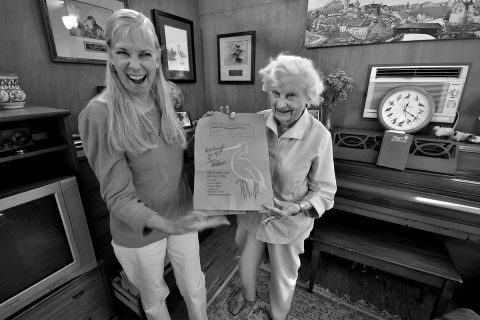

She estimates about 400 people showed at the congressman’s hearing. Most were supporters, waving the committee’s “Save the Wetlands” auto shades, mimicking a flock of the herons illustrated on them.

After a long campaign, the congressman’s bill passed in 1988 and was signed by President Ronald Reagan. It gave the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service the green light to acquire up to 20,000 additional acres.

“The Fish and Wildlife Service is what we chose to protect our bay years ago, and I have never regretted that,” LaRiviere said.

Rukeyser was advised to get the owner’s name “out in public” with his photo, LaRiviere said.

The two-year effort culminated with a provocative full-page advertisement in The New York Times’ west coast October 8, 1996, edition.

The Nobles and LaRivieres wrote the text, Feinstein said, which asked the company’s owner to let Bair Island go back to nature. It also listed the Japanese environmental organizations supporting the effort – a lasting benefit from LaRiviere’s earlier role as a wetlands ambassador to Japan.

Less than a month later, “my phone rang, and it was the head of refuges around here, Rick Coleman,” LaRiviere said. Coleman told her that Kumagai called and said, “Let’s talk.”

“Boy, I’ll never forget that,” she said.

Within a year, Bair Island was purchased and deeded to the refuge. In 2003, the refuge acquired 9,000 acres of former salt ponds for restoration. Alongside the state, the California State Coastal Conservancy, and a host of other partners, the effort to restore these acres and an additional 6,000 acres in state ownership has become the largest wetland restoration effort west of the Mississippi River.

“These are lasting examples of what can be accomplished when people work together, but it always takes a leader with persistence and vision to start and sustain those efforts,” said David Lewis, who has been at the helm of Save The Bay for 20 years. “I love Florence for what she has accomplished and for inspiring others to emulate her.”

The refuge’s latest complex manager, Anne Morkill, places LaRiviere among her personal conservation heroes – Rachel Carson, Margaret Murie and the women who started Save The Bay.

These women are incredible community leaders, Morkill said. “It’s very selfless work. They dedicate their entire lives to protecting wildlife and their habitats and the community… They go to D.C. to lobby, work with regulators, work with citizens, review tedious documents that we agencies put out there. It’s amazing… That’s what’s always inspiring to me.”

Within the refuge’s 30,000 acres is a 100-acre marsh and former salt pond. Now flush with native plants and wildlife, it was named LaRiviere Marsh in 2013. When LaRiviere spoke of it, a grin spread across her face, and her eyes glowed.

“The Fish and Wildlife Service has given us the greatest honor by naming that beautiful, lovely, endangered-species-rich marsh after us, after my husband and me,” she said. “But it should be named for about 20 or 30 people that all of whom gave so much of themselves, of their time and energy and their love to this land and the creatures.”

The dedication illustrates the fervor with which the LaRivieres pursued bay protection as a team. LaRiviere’s husband, who died in 2012, would pore over environmental documents and “with withering accuracy, contradict and correct developers’ consultants’ statistical analyses,” Feinstein said.

Philip LaRiviere adopted the title “swamp physicist,” and handed out business cards on which he’d sketched himself in shin-height marsh peering through a magnifying glass. “You have to have a little fun,” LaRiviere said as she held his cards.

LaRiviere – now a great grandmother – still gathers people around her kitchen table in that same Palo Alto home. While she continues to drive conservation into the future, her 1951 home oozes of decades past.

The exposed beams, glazed walls and low-gabled roof remain true to the subdivisions designed by Joseph Eichler for World War II veterans and their families in California. The furniture follows mid-century clean lines and simple shapes, but with family photos and remembrances tucked in every corner.

It’s tidy, too, of which LaRiviere is proud. She’s navigated the walls of books and files in the homes of many environmentalists, and laughed recalling a visit to a friend’s home. “When I got to the bathroom, I had to laugh,” she said. “The bathtub was full of papers. The bathtub! I don’t know what the woman did… I have never felt so bad about this house after that.”

Perhaps it’s not the house, the tidiness or the furnishings that mattered at all, but the space it gave to her life’s work and her family. LaRiviere and her husband raised their four children in this home.

For decades it has welcomed LaRiviere’s vast network, whether they were guests for her three daughters’ wedding receptions, a church friend recovering from surgery, or a homeless man with no place to watch a presidential inauguration. "That’s my mom,” her daughter Ginny LaRiviere said. “It’s all about doing what’s right.” No one wants her to change anything, she said.

What has changed is the steady wave of awards and recognitions washing over the wood paneling. They line the office and the television room, and are so numerous that some remain stacked on shelves. They name LaRiviere and her husband, or the committee, or just LaRiviere.

There are awards for lifetime achievement, wetlands conservation leadership, outstanding contributions, endangered species recovery, and a special commendation. Presenters range from Environmental Law Institute, Chevron, and Eddie Bauer to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, The Bay Institute, and the League of Conservation Voters.

The sacrifices made to achieve award-winning advances in conservation are not lost on Carin High, committee co-chair.

"One thing she had promised her family was that after they were successful in saving Bair Island, she would pull back from things,” High said. “And of course that came and went. The fact they have been willing to share her with us is really a credit to the rest of her family. She and Phil were just such a force to be reckoned with.”

Together, the Citizens’ Committee to Complete the Refuge, Save The Bay, Audubon, the Sierra Club, and dozens of other environmental organizations and agencies kindled what some have called an environmental renaissance in the bay. High said the committee aims to add another 10,000 acres to the refuge.

“The thing Florence has really taught us is that you have to be in it for the long haul. It’s good to be passionate and ‘rah-rah’ and fight a fight, but you can’t get discouraged. You have to be willing to pick yourself up and dust yourself off and get back into it.”

On a day last November, LaRiviere’s daughter Ginny took her back to where it all started. They rode in an old gray Honda Civic, LaRiviere’s curled white hair barely rising above the passenger seat. She wore fish-shaped earrings, a matching blouse and fleece, crisp trousers, and flats. That day, black-necked stilts poked around the marsh, and wintering ducks sailed the ponds.

Visitors walked and biked the road along the marsh. Some sat on benches and looked out over the water. A photographer sought the shorebirds’ perfect angle.

LaRiviere and her daughter moseyed down the boardwalk, a light breeze ruffling their hair. While LaRivere no longer sees where the bay touches the sky, it lives on in her mind’s eye.

“If you care enough, and if you have staying power, you can bring about great things,” LaRiviere said.