I have always been drawn to nature and outdoor spaces. My stepdad, who was White, instilled a love and appreciation for being outside and taking advantage of whatever nature had to offer.

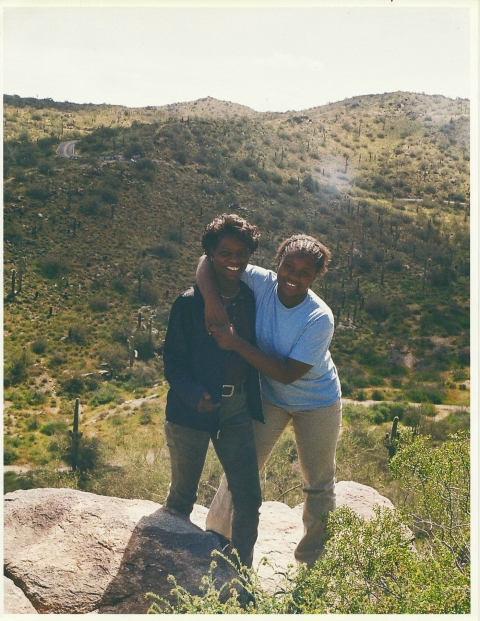

Born and (mostly) raised in Washington State, I had access to endless green spaces. My stepdad was more likely to let me explore more remote or precarious places, while my mom was more conservative in how she interacted with outdoor spaces. For her, going to a city park or visiting a zoo were sufficient and fulfilling experiences with nature. My mom was acutely aware of the world around her, even if I was too young to understand some of the invisible boundaries that seemed to exist. She always had somewhat of an uneasiness in certain outdoor spaces. But my passion forced her to confront and overcome her feelings, and soon we began regularly exploring botanical gardens and wildlife refuges. Some of my better childhood memories are of my mom and I visiting nature trails at Nisqually National Wildlife Refuge or spending the day at Point Defiance Zoo and Aquarium.

Those fond memories often felt overshadowed by an unstable upbringing. My stepdad was a Vietnam War veteran that suffered from PTSD and borderline schizophrenia. My mom struggles with PTSD, bipolar disorder and dissociative identity disorder, none of which were diagnosed until much later in her life. As I grew older and became more aware of my situation at home, being in green spaces grew from a predilection to a necessity. Being outside brought calmness and stability to my otherwise chaotic world. As my environment became more unstable over time, my adolescence was spent in places where I didn’t have access to the outdoors in ways that I had grown used to during my childhood.

As a result, my passion for being outdoors wasn’t nurtured to the point where I understood how to pursue a career in natural resources. Even so, that career didn’t seem like it was for me considering the lack of representation from Black conservationists. What I can only assume was a combination of transgenerational financial struggles resulting in a harrowing lack of wealth accumulation, and a fear that the cycle will continue to perpetuate itself upon future generations, my mom, and family to a lesser extent, strongly advised me to major in a field with sufficient job opportunities and high earning potential. Since I excelled in life science courses, I majored in Biochemistry with a goal of becoming a medical doctor. I maintained my interest in nature through college, and I even spent 3-weeks in Thailand learning about bird ecology and taking part in a coral reef conservation and restoration project. It was an amazing experience, but still, I was convinced that type of career was a pipedream, and certainly not pragmatic.

I went on to pursue a PhD in Biochemistry and Biophysics. It wasn’t until within a year of finishing my doctoral program that I changed my career trajectory. It started with meeting Wanda Crannell, the advisor for the Oregon State University MANRRS chapter. I accompanied the chapter to my first National MANRRS conference where I met and networked with hundreds of Black professionals that worked for companies and agencies across the natural resources and conservation sectors. That was the first time I identified a way to bridge my passion for nature and abilities as an emerging research scientist. By way of a MANRRS hosted trip to the FWS National Animal Forensics Laboratory, I learned of the DFP program, applied and in 2017 was chosen for a project at the Idaho Fish Health Center. I was hired in 2019 by Abernathy Fish Technology Center where I was a Fish Biologist in the Ecological Physiology Program until 2021, when I transferred to the Columbia River FWCO as a Science Communication and Outreach Biologist.

Despite my initial reluctance and eventual success in following my passion and forging a career in the natural resources sector, I am painfully aware of the potential dangers of a Black woman enjoying outdoor spaces. Over the years, the memories of my mom’s uneasiness and distrust began to make sense and I came to understand the reasons for her trepidation that I was too naïve to understand as a child. Most of the time unwelcoming behavior doesn’t go beyond a prolonged stare or an inquisitive look. It doesn’t bother me. I observed the behavior but never addressed it. Occasionally, curiosity will get the better of some folks, and they will feign interest in speaking to me only to ask pointed questions. This is especially true when I’m at archery or firearms ranges, remote wilderness areas or exceptionally small towns.

Rarely, the unwelcoming behavior escalates. One memory, in particular, occurred at the E.E. Wilson Wildlife Area archery park. I was shooting my bow with my headphones on, which is generally accepted to mean “Do not disturb.” Still, I was interrupted by an older White male who demanded to know what I was doing there. I found that question confusing considering I was using my bow at an archery range on public land that is managed by Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Nothing about that situation should have caused him any alarm, except for the fact that there was a Black woman in what he likely felt was “his space.” Even though he never raised his voice, his line of questions and body language were completely inappropriate, somewhat threatening and borderline aggressive.

Unfortunately, far too many Black people have informal training about how to deal with situations like the one I found myself in at a young age. My mind immediately went to my training. Be calm and polite, but assertive. Use your peripherals. Be alert, but not obviously tense. Do not let someone get within two arm distances of you and pay attention if they try to close that gap. But above all, if they try to harm you, and you are unable to safely retreat, make sure you have the means to protect yourself.

It’s commonplace for POC to go through a mental checklist before entering “White spaces,” or areas that are primarily used and occupied by White people. That checklist can vary, but often includes making sure you don’t come across as aggressive or intimidating, knowing how to code-switch, not looking “suspicious” or otherwise up to no good. One thing that is consistent is the unrelenting mental burden that is so deep-seated that it becomes second nature.

Overcoming hardships has made me who I am today, but not without anguish. Interacting with outdoor spaces is restorative for me. Luckily, adversity has never deterred me, at least for too long. I continue to frequent areas where I have felt unwelcomed. I don’t bother to burden myself with another person’s misguided perspective. Learning how to be comfortable in uncomfortable or unwelcoming environments is a skillset I started developing as a child. It’s integral in my steadfast desire to continue returning to the outdoors to show other Black kids that it’s okay to pursue your passion, even if it takes you off the beaten path.