In late 2021 we announced 23 proposed delistings from the endangered species list due to extinction. We had never proposed delisting so many species due to extinction at one time, and based on the massive response, our announcement touched a nerve.

Most of these extinctions happened decades ago, before the act existed and the protections afforded under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) could help. But these 23 stories are so compelling because the reasons these species are extinct are the same reasons countless species are imperiled or declining today — habitat loss, disease, overuse, and inadequate protections.

Wildlife and habitats in the 21st century also face the added threats from climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change including sea level rise, increased frequency and intensity of drought, wildfire and storms, altered growing seasons, reduced snowpack, loss of sea ice, and much more. Climate change is multiplying existing threats to numerous species and natural areas.

The emperor penguin and Mount Rainier white-tailed ptarmigan are two of the first species proposed for protection under the act primarily due to the impacts of climate change and the resulting ecological transformations. More are likely to follow. In Hawaii, increasing temperatures are fueling the spread of invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

Learn more about invasive species and diseases among species already at the brink of extinction.

Emperor Penguin

Reliant upon sea ice and healthy, functioning oceanic ecosystems that support robust populations of krill, emperor penguins face a challenging future against the backdrop of climate change. Using the best available science, we determined that if no greenhouse gas mitigation measures are taken and global temperatures increase up to 4.8 degrees C, emperor penguin populations are expected to decline 47%. Projections for sea ice habitat in some areas are rather dramatic, with three segments declining severely, resulting in 90% declines of penguin populations by 2050 in those areas. Such outcomes would leave just two other populations in the wild. Even if warming can be maintained at 2.0 degrees C with greenhouse gas mitigation measures, emperor penguin populations are still expected to decline 27%.

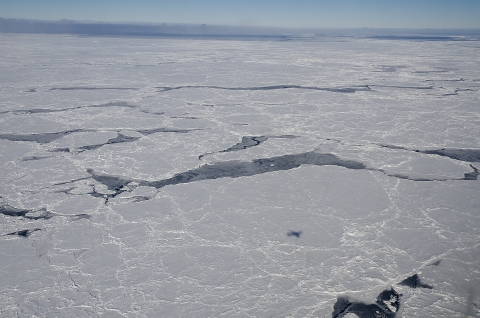

The Climate Change 2021 Physical Science Basis report published by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) highlighted increasingly warmer temperatures over the past four decades. According to the IPCC Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate report, ice sheets in parts of Antarctica have been melting. Emperor penguins rely on stable sea ice during the breeding season to shelter from harsh conditions, as breaks in the ice could lead to death, stranding, or losing a chick before it develops waterproof plumage, according to Yale Climate Connections. Sea ice is also essential for food resources, molting, and protection from predators.

Because of these findings in August 2021, we proposed listing emperor penguins as threatened under the ESA with a rule that provides exceptions for activities that are traditionally allowed under the Antarctic Conservation Act. The listing would provide immediate protections for the emperor penguin, such as prohibiting import, export, possession, sale, or take of the species including harassing, harming, capturing, collecting, or killing them. It also provides support for conservation partnerships. Scientists say that conserving emperor penguins and countless other species that call the Antarctic home will require more than ESA protections. A global reduction of greenhouse gas emissions would make strides toward ensuring emperor penguin populations across the Antarctic remain stable.

Mount Rainier White-Tailed Ptarmigan

Mount Rainier white-tailed ptarmigans are uniquely adapted for living on alpine mountaintops of the Cascade Range in Washington and southern British Columbia. They change appearance throughout the year to match their environment, turning all-white in the winter when they live in snow. White-tailed ptarmigans depend on alpine meadows for finding food, raising young, and avoiding heat stress in the summer. In the winter, they need quality snow for roosting and predictable snow patterns to ensure their plumage matches their surroundings to avoid predation.

As climate change alters alpine ecosystems faster than species can adapt through natural evolutionary processes, the special characteristics of ptarmigans and other alpine species are actually working against their survival.

Due to climate change, the Cascade Range is experiencing and will continue to experience a loss of glaciers, reduced snow amount and extent, and changes to the timing of snowfall, in addition to rising treelines. These threats to the Mount Rainier white-tailed ptarmigan are exacerbated by other risks such as predation and recreation.

Climate-related changes in the Cascade Mountain range could lead to a loss of up to 95% of Mount Rainier white-tailed ptarmigan habitat, based on one model. This loss of alpine vegetation is significant not just for the ptarmigan, but for other alpine species as well. Migration north to Canada is unlikely to help, given similar climate changes and habitat loss there. Under both moderate and high carbon emission scenarios, including those incorporating management interventions to aid the species, only one to two of the six known populations of ptarmigan would remain within 50 years.

As such, in 2021,we proposed to list the species as threatened under the ESA with a 4(d) rule. Conservation measures would include increasing knowledge of the species to better understand the threats and risks, determining where habitat is most likely to persist as the climate warms, implementing strategies to reduce other threats such as recreation and land degradation, or identifying ways to manage the habitat that resists the effects of climate change. These efforts would complement existing work already underway including white-tailed ptarmigan research conducted by the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, the Washington-British Columbia Transboundary Connectivity Project that developed actions for benefiting ptarmigan, and ptarmigan surveys conducted in Mount Rainier National Park and North Cascades National Park. Through collaborations with other federal agencies, states, Tribes, and researchers, steps can be taken toward survival.

Hawaii

A Hawaiian honeycreeper, the Kauai ‘O’o was one of the 23 species recently proposed for delisting due to extinction, the result of critical forest habitat loss from the introduction of non-native species and avian malaria. In total, eight of the proposed 23 delistings due to extinction are Hawaiian forest birds.

Given its geographic range, unique topography, and extreme isolation, Hawaii is home to species found nowhere else in the world. It is also home to more ESA- listed species than any other state, with our Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office overseeing more threatened and endangered species than all other field offices combined. While most of these species are imperiled by the same threats that caused the O’o’s extinction, the impacts from climate change are now greatly multiplying these threats and their interactions.

In total, only 17 of Hawaii’s 50-plus native honeycreeper species remain in the wild, with nearly all of those facing shrinking ranges and declining populations. These extinctions and declines began centuries ago, when mosquitoes were first accidentally introduced to the Hawaiian Islands. These mosquitoes along with diseases (avian malaria), first found in the pet bird trade in the 1900s, have devastated island bird populations that had no previous exposure to or defense against these diseases. As such, wherever honeycreeper ranges have overlapped with mosquitoes, those populations have disappeared.

On the island of Kauai, every species of native forest bird is in decline. On the island of Hawaii, which is higher in elevation than Kauai, seven species of honeycreeper are impacted by avian malaria. Exposure to the disease is fatal or severe for five of these species, all of which are now found only in disease-free habitat at upper elevations. For instance, 90% of the population of Hawaii’s most famous honeycreeper, the ‘i’iwi, is confined to a narrow band of forest on the windward slopes, between 4,000 and 6,000 feet in elevation. These birds survive only at higher elevations where it is still too cold for mosquitoes. Climate change, however, is rapidly shrinking these former strongholds.

Increased temperatures are allowing the upslope migration of avian-malaria-carrying mosquitoes in Hawaii. This dynamic is threatening species already on the brink of extinction, such as the kiwikiu and ‘akikiki honeycreepers, each of which has less than 200 individuals remaining in the wild.

“We are at this point where some of these populations are so low or so dependent on a single area, that a single catastrophic event could spell the end of a species,” says Josh Fisher, one of our invasive species biologists. “There’s an urgency now that didn’t exist before because warming temperatures are already starting to push mosquitoes into the upper elevations of places like Kauai. There really isn’t anywhere else for these birds to go. They can’t go down and they can’t really go up much higher.”

To combat these challenges, the Service and conservation partners are innovating, turning to the “Incompatible Insect Technique,” which has never been used before to address avian malaria in the wild. With our conservation partners, we are testing the release of male mosquitoes treated with a naturally occurring bacteria to prevent reproduction. This method acts like birth control for mosquitoes and has been used to protect humans against mosquito-borne illnesses. The current plan is to begin releasing treated male mosquitoes at a landscape scale sometime in late 2023.

What the Future Holds

Climate change is already touching every continent and ecosystem on the planet and future extinctions due to climate change are all but certain. At least one such extinction, the Bramble Cay melomys, has already occurred. This small Australian rodent lost its sand and coral island habitat in 2016 due to sea level rise.

The most recent IPCC report further underscored both the urgency and scale of the challenge and called for immediate, global action in addressing the cause of climate change and in developing strategies to help people, ecosystems, and wildlife adapt to its impacts. We’re doing both, through conservation partnerships, through strategies like nature-based solutions, and through new conservation frameworks like Resist-Accept-Direct.

The Biden-Harris administration’s America the Beautiful initiative that is aimed at connecting and restoring 30% of lands and waters by 2030 will also help. One of the initiative’s goals is to enhance wildlife habitat and improve biodiversity — to keep species from reaching the point where they are in danger of extinction or are too far gone to save.

- This article is from the spring 2022 issue of Fish & Wildlife News, our quarterly magazine.

- More Fish and Wildlife News.