CLICK HERE FOR THE INTERACTIVE STORY

The prehistoric-looking wood stork stands four feet tall with a white feathered body. Iridescent green and black distinguish its flight feathers and tail. Its slate-colored pebbly bald head, little black eyes, and large heavy bill has earned it the name of “Old Flinthead.”

Wood storks nesting in the United States nearly disappeared by the 1970s. The breeding population of 20,000 nesting pairs in the Everglades during the 1930s shrank to less than 5,000.

“It was rare to see a wood stork in those days,” remembered Billy Brooks, fish and wildlife biologist and wood stork recovery lead for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “We got a letter from John Ogden, representing The Audubon Society. He said wood storks in the United States were on a pathway to extinction by the end of the twentieth century.’” John Ogden was an influential conservationist and authority on wood storks. His letter led to the listing of the wood stork as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 1984 and the creation of a recovery plan. It highlighted the need to restore the Everglades.

"The listing rallied the troops,” said Brooks.

But at the same time, biologists discovered that wood storks were moving out of south Florida to form new nesting colonies in wetlands scattered throughout the Southeast. This prompted the USFWS and state wildlife agencies to collaborate with conservation groups, government agencies, and private landowners in Florida, Georgia and South Carolina to protect, restore and even build wood stork habitat.

A wood stork stalks prey by feel, moving slowly through the water, its big thick bill snapping shut when it finds a fish using a hunting method known as tactile foraging. They breed when wetland water levels are decreasing, and prey is abundant while their chicks are growing rapidly. Wood storks nest in colonies, building homes in trees on islands or trees emerging from water. Alligators nearbydeter raccoons and other predators from eating their eggs and young.

Creating the conditions that entice them to form breeding colonies isn’t easy. Wetlands must have enough prey to feed growing chicks, cypress trees must be planted and cared for, and stands built for nests until enough trees are mature. Water levels must be managed to imitate seasonal wet and dry periods, and floating invasive weeds must be removed. All on a landscape scale. It requires a holistic multidisciplinary approach over the long run. But the collaboration and hard work are paying off.

Since wood storks were listed, they’ve doubled their breeding population – to a total of 10,000 or more nesting pairs – and more than tripled their number of nesting colonies. They can now be found in six states.

“The wood stork is the iconic species that brought about the desire to restore the Everglades. It opened a big area of research looking at the native species as indicators of the health of wetlands, water quality and quantity, and coastal resilience,” said Brooks.

Audubon & Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary

Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary near Naples, Fla. occupies about 13,450 acres in the heart of the Everglades. This is the historical site of the largest nesting colony of wood storks in the nation that occupied one of world’s last remaining virgin bald cypress forests.

Federal- and state-listed species that also make the swamp home include the Florida panther, Everglade snail kite, American alligator, gopher tortoise, Florida sandhill crane, limpkin, roseate spoonbill, snowy egret, tricolored heron, white ibis, Big Cypress fox squirrel, and the Florida black bear. The elusive and rare ghost orchid is also found here.

Audubon Florida has been involved since the early 1900s in the protection of Big Cypress: guarding the rookeries from plume hunters; stopping the over-logging of old growth cypress forest; preserving the watershed from development through conservation easements. Audubon bought the land in the mid-1950s. But it was the mass decline of wood stork numbers that drove a larger approach to species restoration.

“The idea that the wood stork is an indicator of ecosystem health overall drove our approach,” said Dr. Shawn Clem, research director for Corkscrew. “We can’t only look at the species population. We need to look at the ecology and how they use the landscape.”

Clem inherited a data set dating back to the 1950s. “A complex suite of factors makes us look at all aspects of the ecology,” she said. By digging into the data, she saw a long, slow decline in wood stork numbers since the 1960s. Then in the early 2000s Clem discovered a pattern where the wood storks chose not to nest at Corkscrew coinciding with a time when water levels were dropping suddenly.

“Water drives fish, fish drive nesting,” she said.

The water level changes reduced the quantity of fish to feed chicks and caused woody plants to spread, keeping the birds from foraging for fish. Today, Audubon has nearly finished removing 1,000 acres of woody vegetation in the sanctuary, improving feeding conditions. “We are working with the South Florida Water Management District to address the hydrologic changes to help ensure the long-term viability of this habitat,” she said.

Clem said she is encouraged by the wood storks’ adaptability to nest closer to urban areas and create new colonies in southeastern states. “But we can’t lose focus on our effort to restore and conserve their historic habitat in the Everglades.”

Wildlife Sanctuary & Wood Stork Rookery

Private landowners own approximately 70 percent of the land in North America, making them instrumental to restoring habitat for the wood stork and other wildlife. Since 2005, private landowners in the southeastern United States restored 6,254 acres of habitat in 179 projects that benefited wood storks and other wildlife. (HabITS - Habitat Information Tracking System, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service)

On the outskirts of Tallahassee, Fla., Jim Stevenson and Tara Tanaka manage a wildlife sanctuary, home to 275 nesting wood storks. They bought their house almost 30 years ago, then purchased the adjoining 45-acre cypress swamp in 2007 to protect it. Other wading birds take refuge there, including great blue herons, great egrets, little blue herons, and green herons. Anhinga, common gallinule, wood duck and black-bellied whistling ducks also nest in their swamp. Roseate spoonbills visit. Bobcats, raccoons, red and gray fox, otter, beavers, coyotes, and marsh rabbits roam the property.

The couple have dedicated their lives to conservation. Tanaka is an award-winning wildlife photographer and videographer. She’s an expert in digiscoping, attaching a high-magnification spotting-scope to her camera to take closeup photos from afar. Stevenson is a retired state park biologist.

“Our work has converged to support this effort,” Tanaka said.

Even before they bought the property, Stevenson would paddle his canoeinto the swamp to pullChinese tallow trees out of the water by hand so wood storks could forage. He sets prescribed fires on the surrounding land to manage the habitat for wildlife. When thick vegetation on floating islands threatens to choke out the open water, they bring in a mechanical harvester to remove it. Stevenson created a small island for resident alligators to use for sunning. The alligators deter raccoons from raiding the wood storks’ nests.

Tanaka recognizes individual wood storks. “I love seeing them come back year after year,” she said. “When I look out of my office window, I watch them land in the big water oak in our backyard and collect sticks for nesting.”

In 2016, the Apalachee Land Conservancy placed a conservation easement conservation easement

A conservation easement is a voluntary legal agreement between a landowner and a government agency or qualified conservation organization that restricts the type and amount of development that may take place on a property in the future. Conservation easements aim to protect habitat for birds, fish and other wildlife by limiting residential, industrial or commercial development. Contracts may prohibit alteration of the natural topography, conversion of native grassland to cropland, drainage of wetland and establishment of game farms. Easement land remains in private ownership.

Learn more about conservation easement on their property in perpetuity, making it easier to protect the sanctuary. “No shooting, no fishing, even the frogs are protected,” said Tanaka.

Their wood stork colony has slowly grown through the years. Biologists from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission discovered a stork banded in the Everglades in their rookery in 2010. Tanaka spotted another wood stork collecting nesting material in their backyard that had been banded in Jenkins County, Georgia in 2010.

Before the pandemic, Stevenson and Tanaka taught private landowners how to manage their land for wildlife. “That is where the real need is. Landowners are eager to learn about managing their land for natural conditions,” said Stevenson.

He taught the value of prescribed fire, native plants and wildflowers, and how to manage for wildlife. The quarterly classes were filled to capacity with 45 to 50 people attending. “Natural and restored lands held in private ownership by people and organizations who genuinely care about them will have to play a role in the future of wildlife protection,” Tanaka said.

Harris Neck National Wildlife Refuge Wood Stork Rookery

Woody Pond at Harris Neck National Wildlife Refuge hosts the largest wood stork colony in Georgia and one of the most productive colonies in the southeast with an average of 450 nesting pairs. As chicks fledge from Harris Neck, they create new colonies in Georgia and South Carolina. “Harris Neck has been successful because we have made it a priority, where we spend time, money, energy and resources,” said wildlife refuge manager Kimberly Hayes.

Wood storks have used Harris Neck as a roosting site since the late 1970s, but it wasn’t until 1987 they were documented nesting on Woody Pond. In 1990 the refuge began improving nesting habitat there for wood storks. Workers raised the levee to flood a larger area, installed a new pump to provide enough water, and built nesting islands. With too few cypress trees for nesting, staff built artificial nesting platforms out of four-by-fours with netting draped over rebar.

Volunteers and employees planted cypress trees on the newly constructed islands. Alligators wallowed on the saplings, so they planted bigger trees and installed shelters around them until the trees matured. Wood storks took to the artificial platforms and nesting increased every year. Once the cypress trees reached 25 feet in height, the storks abandoned the artificial platforms for the trees. Workers have planted more than 400 trees in the last few years.

“A rookery has a life cycle. They are not meant to last forever,” she said.

The trees take a beating. Nesting wears them down, storks pull branches off the trees, and the birds cover everything in guano. Upkeep of the colony is continual. Between existing rookery maintenance and an increasing wood stork population, Hayes determined more nesting habitat was needed. Twenty-five cypress trees have been planted in Snipe Pond, adjacent to Woody Pond. Once the trees reach the necessary height for the storks, staff will flood the area around the trees.

“The highlight for me is our volunteers,” Hayes said. She uses volunteers from the local community, universities, and organizations such as the Student Conservation Association to monitor the wood stork colony. “The data they collect is used for the recovery plan,” she added.

Woody Pond is one of a series of six ponds on the wildlife refuge that, along with salt marshes, open grassland, forested wetlands and mixed hardwood and pine forests, attract migratory birds. In addition to wood storks, 83 bird species breed at Harris Neck, and 342 species have been identified.

“I feel very fortunate to know I have had an opportunity to contribute to the recovery of a species, to actually see it,” Hayes said.

Washo Reserve Wood Stork Rookery

The Washo Reserve’s 200-year-old freshwater cypress lake and cypress-gum swamp harbors the oldest wading bird rookery in continuous use in North America. The wetlands are holdovers from old, impounded plantation rice fields. The reserve is a 1,040-acre natural area in Charleston County, South Carolina. The Nature Conservancy owns and co-manages it with the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources.

More than 250 nesting pairs of wood storks oncenested at the reserve. A decade ago, though, the degraded habitat slowly reduced their numbers to 150. As the reserve manager, Colette DeGarady from The Nature Conservancy oversaw the transformation to a healthy rookery. The cypress trees were dying. Mats of dense aquatic vegetation choked the water around the nests, allowing predators to reach the eggs and chicks. The agencies needed to draw the water ownd around the nests to treat the weeds and plant new trees.

“Wood storks want to see open water under their trees, or they won’t nest there,” DeGarady said.

They used aquatic-approved herbicide to reduce floating vegetation, but they needed to plant trees without flooding them or drawing the water down. So, they tried something new: they planted 275 cypress saplings inside the trunks of the old growth dead cypress stumps scattered throughout the 200-acre wetland. The trunks protected the saplings from flooding. “It was a way to give them a head start,” DeGarady said.

Wood stork habitat restoration and species management requires continual efforts from everyone involved. But then, the wood stork recovery effort has shown it is only as successful as the partners that drive it – making the collaboration as iconic as the bird itself.

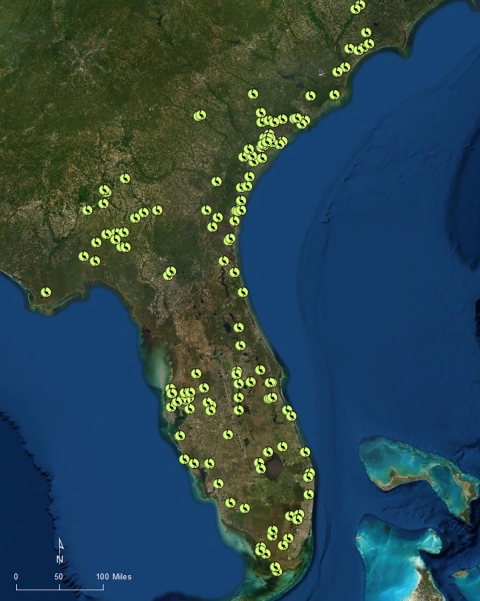

Wood Stork Nesting Colony Locations

The wood stork breeding range occurred mostly in south and central Florida with a small number of small nesting colonies in north Florida and coastal Georgia and South Carolina at the time of listing. The current breeding range now includes all the coastal plain of Florida, Georgia, South Carolina and southeastern North Carolina.

This map shows wood stork breeding range from 1970 to 1974.

This map shows wood stork breeding range from 2015 to 2019.

Wood Stork Photos

Mark Cook is the Section Leader of the Systemwide Everglades Research Group in the Applied Sciences Bureau of the South Florida Water Management District. His research has focused on the restoration and management of birds and aquatic fauna in the Everglades and Florida Bay. Mark uses his photography to inspire a greater appreciation of our natural heritage with the goal of effecting its conservation. He has published his images in newspapers, magazines and scientific journals, exhibited his work at galleries, and has won awards in international competitions.