By Lilian Carswell, Southern Sea Otter Recovery and Marine Conservation Coordinator, Ventura Fish and Wildlife Office

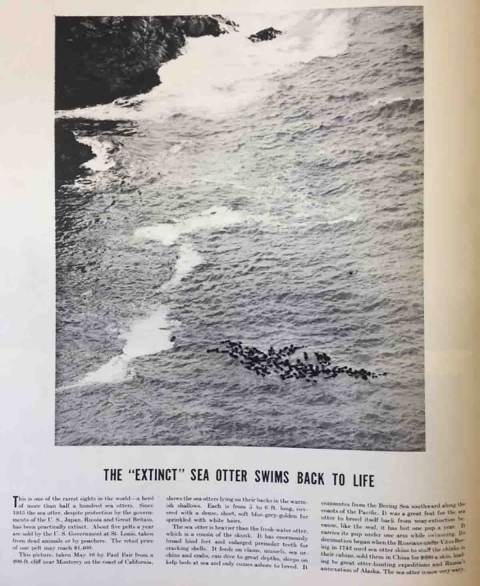

People traveling on California’s newly built Highway 1 in 1937 saw something astonishing. Far below their vantage point at the edge of the rugged Big Sur cliffs, tossed on rough waters, was a cluster of buoyant, dark forms. On June 20, 1938, Life magazine published a photo of what it called “one of the rarest sights on earth”—a large raft of sea otters near Bixby Bridge, south of Monterey. Its headline proclaimed, “The ‘extinct’ sea otter swims back to life.”

The Maritime Fur Trade

The sea otter’s brush with extinction began far away from those rocky shores, in the Russian Far East. Aboard the ship Svyatoy Petr (Saint Peter), Vitus Bering’s second Kamchatka expedition foundered in storms and wrecked near an uninhabited island, later named after Bering himself, who was buried there. From the moment Bering’s men returned home to Russia with sea otter pelts, the species was in mortal danger. It was 1742. With more hairs per square inch than those of any other mammal, the thick, lush furs fetched enormous sums.

Other Russians soon returned to obtain more furs, forcing skilled Aleutian hunters to join their hunting expeditions. The money to be made sparked a multinational fur rush, involving Russian, Japanese, Spanish, British, and American traders. While some Native peoples within the sea otter’s range had traditionally conducted local hunting of sea otters, the scale of slaughter in the maritime fur trade was unprecedented, nearly eliminating sea otters from their global range.

Before the fur trade, the range of sea otters spanned the entire North Pacific rim, from the northern islands of Japan to midway down the Pacific Coast of Baja California, Mexico. By the time the International Fur Seal Treaty was ratified in 1911, prohibiting the hunting of sea otters in international waters, only 13 remnant populations, each numbering an estimated 10–100 animals, survived globally. Two of these populations disappeared by the end of the decade.

The population off Big Sur was the most isolated of all of these, separated from any other surviving sea otters by about 2,000 miles. These sea otters were the only living representatives of the subspecies that came to be known as the southern sea otter (Enhydra lutris nereis).

Back from the Brink

In 1911, most Californians weren’t thinking about sea otters. Those whose grandparents remembered there were once weasel-like animals living along the cold Pacific shorelines of North America thought they were extinct, or at least extirpated from the lower 48. And for the most part, they were right. But a few biologists working for the California Department of Fish and Game had a secret: There was a tiny, precarious population that had survived near Bixby Cove, off California’s central coast. These animals were in danger, and state officials knew it.

Sea otters are a shallow-water species, spending their lives within depths where they can reach the bottom for food, so the sea otter’s range tends to hug the coastline, visible to and easily within reach of hunters.

The ban on hunting in international waters did little good for southern sea otters in nearshore waters, which were administered by the state, and by then sea otter skins were selling for more than $1,500 each, about $44,000 in today’s dollars. In 1913, California declared the sea otter a “fully protected mammal.” That designation made it a “high misdemeanor” to kill or possess them.

In 1915, a California Department of Fish and Game biologist reported sightings by local residents of up to 32 sea otters at any one time. The biologist attributed this improvement from their “near-extermination” just a few years earlier to the state’s total protection.

Sea Otters and Abalone

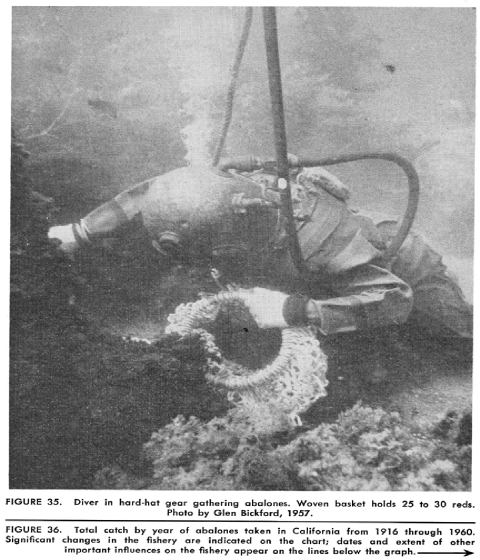

Sea otters began slowly and methodically to expand their range to the north and south of Bixby Cove. In the 1960s, they reached the waters of Gorda and San Simeon, north of Morro Bay, prime fishing grounds for a lucrative commercial abalone fishery that had begun in earnest after World War II.

By this time, several generations of Californians had lived and died in a world essentially devoid of sea otters. With one of their main natural predators absent for so long, abalone could be found exposed on rocks instead of hidden in crevices, sometimes piled several animals deep. When the sea otter returned and began to compete for these same shellfish, some saw the sea otter as an interloper, a destroyer of the ocean’s bounty. But to understand the sea otter’s relationship with abalone, and with other organisms in the nearshore marine communities of the North Pacific Ocean, we need to go back in time.

Unique Physiology

The ancestors of sea otters diverged from freshwater mustelids about 5 million years ago, making the sea otter the most recently derived of all marine mammals. Sea otters are also the smallest marine mammal in the northern hemisphere. This puts them at a high potential for heat loss, especially because, unlike most marine mammals, sea otters do not have blubber to insulate them.

Their dense coat is one of two primary adaptations to maintain internal body temperature. The other is a metabolism more than double that of any land mammal of the same size. To fuel this metabolism, sea otters need to consume about a quarter of their body weight in prey each day.

A Keystone Species

Although abalone are a favorite prey item, they make up only a small proportion of the diet of the sea otter population overall, the remainder consisting of several dozen species of marine invertebrates, including many kinds of crabs, clams, sea urchins, mussels, chitons, octopuses, sea stars, and marine worms. The appetite of the sea otter is a threat to individual abalone who have not hidden themselves in deep rocky crevices, but where sufficient crevice habitat is available, this same appetite brings benefits to abalone populations.

By consuming sea urchins who are not similarly hidden, sea otters change sea urchin behavior. Instead of roving about and attacking the holdfasts that anchor living kelp to the rocky ocean floor, creating “urchin barrens,” fearful sea urchins adopt a “sit-and-wait” strategy, hiding in deep crevices and eating only those pieces of kelp that break off and drift down. This same drift kelp feeds the abalone. Without it, they starve. In a study on black abalone, which were listed as endangered in 2009 due to the combined effects of past overharvesting and a devastating disease called withering syndrome, researchers found that the highest densities of black abalone occurred in areas with the highest densities of sea otters. Because of sea otters’ role in protecting kelp forests, they impact the lives of not just abalone but hundreds of other species that depend on the shelter, food, or substrate provided by kelp.

The sea otter’s “keystone” role in nearshore marine ecosystems was first recognized in 1974, initiating an extensive body of work on sea otters’ indirect effects, including increases in the abundance of kelp-associated finfish. Since then, researchers have learned more about the complementary roles that other sea urchin predators, like sea stars, play in controlling overgrazing by sea urchins, but the conclusion that sea otters defend kelp patches and help to promote eventual regrowth has not changed. Researchers have also uncovered other surprising indirect effects, such as sea otters’ beneficial effects on seagrass abundance and even its genetic diversity. Increases in kelp and seagrass due to sea otters can translate into increased carbon sequestration.

Coevolution

Although these ecological discoveries are relatively recent, the relationships between sea otters and other organisms in the nearshore North Pacific, with whom they coevolved for millions of years, are ancient. Evidence of this coevolution may be seen in the bodies of animals, like abalone, today. Researchers have proposed that sea otters and their evolutionary progenitors could be indirectly responsible for evolution of the unusually large body sizes of the abalone species in the North Pacific Ocean. According to this explanation, by defending macroalgae (like kelp) from herbivores that attacked its living parts, sea otters allowed the macroalgae to relax its chemical defenses, making the pieces that drifted down to waiting herbivores higher quality food. This higher quality food allowed abalone species to attain much larger body sizes than those found in other oceans, where the herbivores do not have similarly effective predators. In fact, every species that feeds on these relatively chemically undefended macroalgae of the North Pacific may owe a debt to sea otters.

A New Respect for the Environment

The flourishing of ecological thought in the 1970s was matched by a flourishing of environmental legislation. The 1969 blowout of Union Oil's Platform A off the coast of Santa Barbara sparked the modern environmental movement, leading to the passage of several crucial pieces of federal legislation, including the Marine Mammal Protection Act of 1972 (MMPA) and the Endangered Species Act of 1973 (ESA). Sea otters were transferred from state management to federal management, and in 1977 the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service listed the southern sea otter as threatened. While the ESA focuses on preventing extinction and promoting species’ recovery, the MMPA has a more explicitly ecological aim: to maintain marine mammal stocks at levels where they are “significant functioning elements of the ecosystems of which they are a part.” In other words, marine mammal stocks must be restored to ecological relevance.

Southern Sea Otter Translocation

Sea otters were not affected by oil from the Santa Barbara spill because they had not recovered their range that far south. Still, it was clear that a large oil spill could potentially cause the subspecies’ extinction. In the late 1980s, the Service translocated 140 sea otters to San Nicolas Island, off Southern California. The intent was to create a second population that could provide sea otters to replenish the mainland range in the event of a catastrophic oil spill. The Service terminated the translocation program and its associated zones in 2012. The population at San Nicolas Island remained small for many years because most translocated sea otters had dispersed from the island soon after release, leaving a founding population of only about a dozen animals. However, it eventually began to grow more rapidly, numbering about 100 at the time of the most recent range-wide count in 2019.

Hemmed in by Sharks

Today, there are about 3,000 southern sea otters, and although their condition has improved since the time of ESA listing, they remain far from the MMPA goal of restored ecological relevance. The southern sea otter has reclaimed only about 13% of its historical range, and its population size is far below its estimated historical population size in California, about 17,000 (though it could be as low as 10,000 or as high as 30,000), a number that does not include the historical populations in Oregon and Baja California. Net range expansion has not occurred in more than 20 years, due largely to increasing mortality of sea otters caused by white shark bites, especially at the northern and southern ends of the central California range. To get past this shark “gauntlet” and into safer waters to continue their recovery and return to ecological relevance, southern sea otters will likely need assistance.

Assessing Reintroduction

In 2020, echoing language of the MMPA, the U.S. Congress recognized that sea otters “play a critical ecological role in the marine environment as a keystone species that significantly affects the structure structure

Something temporarily or permanently constructed, built, or placed; and constructed of natural or manufactured parts including, but not limited to, a building, shed, cabin, porch, bridge, walkway, stair steps, sign, landing, platform, dock, rack, fence, telecommunication device, antennae, fish cleaning table, satellite dish/mount, or well head.

Learn more about structure and function of the surrounding ecosystem.” This explanatory language, which accompanied the 2021 Appropriations Act, also instructed the Service to study the feasibility and cost of reestablishing sea otters on the Pacific Coast of the contiguous United States. The Service’s assessment reviews the biological, socioeconomic, and legal aspects of reintroduction feasibility and summarizes known information, key data gaps, and stakeholder perspectives. Read the assessment here.

Despite high attrition, reintroductions using translocated wild sea otters have resulted in about 35% of global sea otter abundance. New methods of reintroduction using juvenile sea otters who stranded as pups and were raised by surrogate sea otter mothers also show great promise. Recent work in British Columbia has shown that the economic benefits of sea otter restoration stemming from finfish increases, carbon sequestration, and ecotourism outweigh the costs many times over, about sevenfold. The Service aims to be inclusive, thoughtful, and scientifically rigorous as we consider actions to support sea otter recovery and ecosystem restoration now and in the future. Input from stakeholders will be critical in informing next steps.

The MMPA’s Next 50 Years

The far-sightedness of the MMPA is only beginning to be realized. As the marine mammal species that it protects return to ecologically effective population sizes, we learn what their roles once were, and more importantly, how they might contribute to ecosystem resilience in the future.