This was the third year of a collaboration on waterfowl banding between the U.S. Fish and Wildlife (USFWS) and the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife (MEIFW) in Aroostook County, Maine. We learned a lot from one another in regards to bird trapping and banding techniques and it was great to share information and grow into more efficient waterfowl banders in the process. Our bird crew this year consisted of Kelsey Sullivan, Wildlife Biologist/Gamebird Coordinator and Brittany Peterson, Resource Biologist, both with MEIFW, and Sarah Yates, Wildlife Pilot-Biologist with the USFWS.

The area of Maine that our banding station was in is unique in the abundance and diversity of waterfowl found here: mallards, American black ducks, wood ducks, ring-necked ducks, and even a few blue-winged teal, gadwall, redheads, and northern shovelers breed in this part of the state. In addition, many birds travel to this area of Maine to complete their annual molt, where they shed their old feathers, during the latter part of July and through the month of August before they continue their fall migration.

We often capture birds that were banded from previous years; these could have been birds banded by us previously, or birds that were banded by another permitted bird bander in a different region. For example, we often recapture birds that were banded in Quebec and travel here to Maine to start their molt. I’ve even witnessed a bird recaptured in Alberta, Canada that was previously banded in Arkansas! There are some exceptional examples including arctic terns that were banded in Maine and recaptured in Ghana, Africa, approximately 4800 miles away!

When we capture and band birds, or recapture a previously banded bird, it is recorded and entered into an extensive database administered and maintained by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Bird Banding Laboratory (BBL). The BBL is a key scientific program where bird researchers can collect information on bird movement and survival and gain a better understanding of bird population dynamics throughout the world. Therefore, bird recapture information is incredibly important!

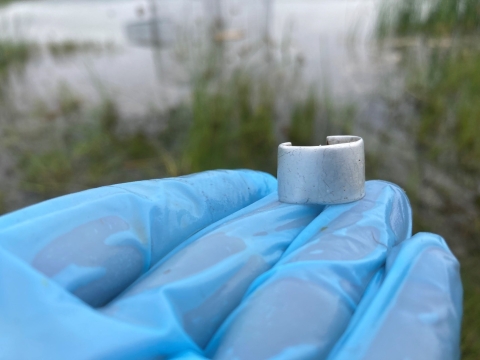

Along with the approximately 400 newly banded birds at our station this year, we also recaptured 67 birds! A few birds had current bands that were so worn the uniquely identifying band numbers could no longer be read (see picture below). In those instances, we replaced that band with a new one and the old bird band was sent back to the BBL so bird researchers could chemically etch the band and retrieve the old band number. Then the band numbers are cross-referenced and that bird information will continue to provide valuable movement and survival information for years to come.