Fort Payne, Alabama -- Caves are, by nature, mysterious subterranean portals to another world. Manitou Cave – a historical gem, a cultural phenom, a conservational wonder -- is supernatural.

The walls of the limestone cavern in northeast Alabama bear some of the first recorded evidence of the written Cherokee language created by the Tribal leader and scholar Sequoyah. Tribal members sought communion with the spirits two centuries ago deep in the bowels of the mile-long cave.

Saltpeter miners scribbled their names on the walls during the Civil War. Later, the mine-turned-tourist-attraction beckoned northerners into its “ballroom” for candle-lit galas. More recently, an adventuring company offered “wild cave tours.”

An exceedingly rare snail has borne witness to, sort of, the cave’s multifarious history. The sight-less Manitou Cave snail lives without light in the chilly stream that runs along the cave’s bottom, and nowhere else. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is considering whether to list the endemic species as threatened or endangered. A decision is expected by 2026.

“Not only is it a historic monument, but it has a neat natural history link as well,” said Paul Johnson who runs the Alabama Aquatic Biodiversity Center and has researched the Manitou snail. “And then there’s Annette. She’s a very interesting lady. I commend her enthusiasm for helping to conserve Manitou.”

Annette would be Annette F. Reynolds, the indefatigable Birminghamian who near-singlehandedly saved Manitou Cave from disrepair and dissipation. Reynolds, 76, took stewardship of the cave nearly a decade ago and has since restored its cultural and natural luster.

“I’m not a caver. I’m not Cherokee. I’m not from around here. I’m supposed to be retired. And I don’t have deep pockets. I had no idea what I was getting into,” Reynolds said before a recent, leisurely tour of the cave. “But people who know me said, ‘Of course she runs a cave.’ I’ve always done things like this – try to make the world a better place and do the things that need to be done. I had a vision, and this is my mission to respect and protect this historic, sacred site through conservation and education.”

Great Spirit Mountain

In 1888, the Fort Payne Iron and Coal Company bought the cave and ran tracks from the Birmingham-to-Chattanooga line to the budding tourist destination near Lookout Mountain. Wealthy New Englanders, drawn by coal and iron ore deposits, built rolling mills, foundries, and steel plants around town. The boom proved short-lived. By 1907, Fort Payne – named for the stockade which held Cherokee families before their forced removal to Oklahoma – had reinvented itself eventually gaining renown as the “sock capital of the world.” Overseas competition sundered the town’s manufacturing capacity. The completion of Interstate 59 allowed motorists to speed on by without learning of Fort Payne’s touristic offerings.

The Cherokee once reigned supreme over much of the Southeast, yet the cave’s northern owners thought the Ojibwe word Manitou – a spirit or supernatural force – would appeal more to tourists. They built a park outside the cave and a series of wooden bridges inside leading to the 60-foot-high ballroom. Reynolds prefers “reflection room” and, during the tour, flipped off her flashlight for a total immersion into darkness and quiet.

On her way down she passed the Great Spirit Mountain, a bus-sized rock column formerly known as “the haystack.” The drip-drip of calcite-rich water over hundreds of thousands of years created the chunky stalagmite. Other, far-out geologic formations – stalactites, soda straws, flowstones – fill the chamber-sized room.

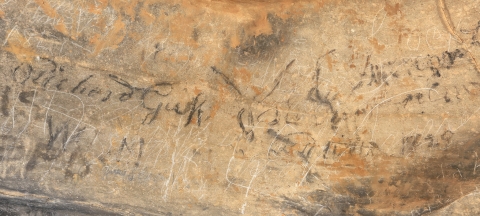

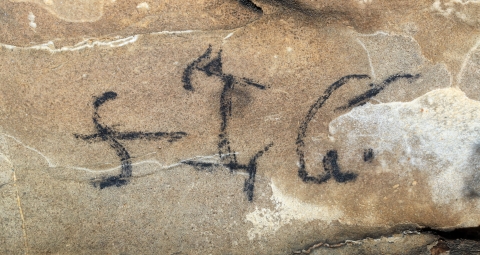

The cave narrowed. Walls filled with inscriptions loomed just beyond the spot where the creek emerged from below ground. Some modern scribblings. Some Civil War-era signatures. And some fascinating, 200-year-old Cherokee writings, either written in charcoal or engraved with sticks or stones.

“This is one of the most important places in the cave – a very historic, archaeologic wall of signatures,” Reynolds said. “This was a very significant place for the Cherokee, in particular.”

Sequoyah, a silversmith and scholar who also went by George Guess, created the Cherokee syllabary, a set of 85 written characters each one representing a syllable or sound. It was officially adopted by the tribe in 1825. Previously, the Cherokee relied upon oral history to tell their story. Manitou Cave affords one of the few, rare examples of Cherokee writing on a cave wall.

Manitou was an important spiritual and ceremonial gathering spot in the midst of a troubled land. White settlers in the early 1800s continuously pushed the Cherokee further west from their homelands in the Carolinas, Tennessee, and Georgia. Many landed in Willstown, now known as Fort Payne. Yet they couldn’t escape the relentless pressure – or worse -- to assimilate into the white, Christian world. Stickball, and the cave, offered some relief.

Stickball games, similar to today’s lacrosse, could last for days and, at times, settled disputes between different Cherokee communities. Players oftentimes ended up bruised and bloodied. They also required a quiet, safe, ceremonial space near water before and after contests. Manitou Cave fit the bill.

One charcoal inscription reads, “Leaders of the stickball team on the 30th day in their month April 1828.” Another, “We who are those that have blood come out of their nose and mouth.” It was signed by Richard Guess, Sequoyah’s son and most likely a spiritual leader.

In 2019 a team of Cherokee and non-tribal scholars interpreted the writings to mean that stickball players gathered deep in Manitou Cave to prepare for, and recuperate from, a match. The players prayed, meditated, danced, scratched, and cleansed minds and bodies with smoke and water.

“The Cherokee and their antecedents considered caves to be powerful places: places where water emerged from the lower world, where the spiritual and visible worlds were close, and where the living could seek spiritual strength in seclusion,” they wrote in the archaeological journal Antiquity.

More inscriptions – written backwards to, supposedly, be legible to the Old Ones living in the spiritual world above – appear closer to the cave’s entrance and 40 feet above ground. The scholars decline to fully translate these charcoal and engraved writings because “they relate to sensitive religious subject matters.”

Julie Reed, an associate history professor at Penn State University and a citizen of the Cherokee Nation, co-authored the Antiquity article. She first visited Manitou Cave in 2015 – and was blown away by what she discovered.

“I remember just being overwhelmed by a lot of very different kinds of emotions,” Reed said in an interview. “What we see on the ceiling, clearly, is a conversation with beings above which is not the same audience as the stickball narrative on the wall. Different authors, different audiences. And that, in and of itself, is complicated and awe-inspiring. I was struck by the sophistication of the writings. One of the things that got driven home to me was, ‘Man, our ancestors were so smart.”

'Mitigate the threats’

Reynolds, during her tour, stopped at one of the bridges over the creek. The water appeared, magically, from a hidden, subterranean chamber. Manitou Cave snails were down there, somewhere, eraser-sized gastropods clinging to a tentative existence.

“What’s so great about a tiny snail anyways?” Reynolds asked, kiddingly.

In 2010, the Service was asked to federally list and protect Antrorbis breweri named for Dr. Stephen Brewer, a local dentist who previously owned the cave. Jeff Powell, a deputy field supervisor for Fish and Wildlife in Alabama, says the agency is investigating whether listing the blind, thin-shelled mollusk is warranted. The Service, and partners, are studying the snail’s habitat, water sources, and possible contaminants – a nearby quarry, subdivisions, highways, and cleared land – to gauge threats to the snail’s existence.

“We could avoid listing it if we’re able to mitigate the threats,” Powell said.

Johnson, the Alabama mollusk expert, first visited Manitou Cave in 2004.

“The only answer is to preserve the spring and cave habitat by keeping the sediment out, and the water quality in good condition,” he said. “We need to get some funds together to, basically, purchase the recharge area which is not that large.”

Saving the snail means, first and foremost, protecting the cave. It was closed to the public in 1979, but that didn’t keep locals from using the so-called “dump” or “swamp” as a party spot. Spray-painted graffiti in green, red and other garish colors welcomes visitors just beyond the cave’s entrance. In 2015, a nonprofit bought the cave, 10 acres and the rundown visitors’ center and turned it over to Reynolds.

Officially, she’s the cave's volunteer director and steward. But, really, she does it all: caretaker; fundraiser; historian; educator; cave guide; community activist; publicist; toilet-cleaner; and conduit between Manitou, conservationists, scholars, the community, and the Cherokee.

“I feel like I’ve been a hamster on a wheel, but I had no idea that this would be so important,” said Reynolds, formerly a registered nurse and creative arts therapist. “The cave, the land, and the water must be protected for visitors and wildlife as a place of peace. It’s not just about one thing or another. A big part of it, yes, is about the snail. But it’s also about education and land conservation and the truth about its history.”

In 2015, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians paid for the 3,000-pound steel gate at the cave’s mouth to keep out ne’er-do-wells while letting in brown and tricolored bats. A year later, the Alabama Trust for Historic Preservation labeled the then-decrepit visitors’ center as an important place in peril. In 2021, Manitou Cave was added as a National Trail of Tears historic site.

Late last year, Reynolds announced she was retiring. Finding a volunteer -- unpaid -- replacement will be difficult. Once again, Manitou Cave’s future, and the protection of the Cherokee syllabary and one very rare snail, hangs in the balance.

“I have given my life to this cave for nearly a decade,” Reynolds said, “and now it’s time for Manitou Cave, and me, to move forward. But I’ll always be deeply connected to the cave. It’s part of me.”