On a gray, November day in 2019, an excavator hammered away at the Tel-Electric Dam until the structure structure

Something temporarily or permanently constructed, built, or placed; and constructed of natural or manufactured parts including, but not limited to, a building, shed, cabin, porch, bridge, walkway, stair steps, sign, landing, platform, dock, rack, fence, telecommunication device, antennae, fish cleaning table, satellite dish/mount, or well head.

Learn more about structure gave way. It was noisy; it was messy; and Jim McGrath couldn’t have been happier.

As Park, Open Space and Natural Resource Program manager for the City of Pittsfield, Massachusetts, McGrath spent 20 years piecing together funding and support for removal of the dam, which was key to the City’s vision of a renewed West Side neighborhood with a free-flowing West Branch of the Housatonic River.

“This is the right thing to do,” he said at the time. “The river is the backbone of the neighborhood— improving the West Branch will improve lives.”

Locally, allowing the river to flow freely has increased recreational opportunities, decreased the risk of flooding, and removed a safety hazard. Wildlife can move throughout the West Branch more naturally, and water quality downstream, to the greater Housatonic and beyond, is improved.

Righting a wrong

Not that long ago, life in Pittsfield revolved around an industrial giant. General Electric was the city’s main employer for the better part of the 20th Century. “The GE,” as locals called it, supported thousands of families across multiple generations through its production of electric power equipment, munitions, and plastics.

But company activities had a dark side, one that didn’t live up to its tag line: “We bring good things to life.” As part of the electrical transformer manufacturing process, cancer-causing chemicals called polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) leaked from factory floors and disposal sites into the West Branch. They settled in the riverbed, leaving a toxic legacy that flowed through two states long after the company left town.

GE closed the transformer plant in 1987. In 1999, the company settled a Natural Resource Damage Assessment and Restoration claim with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the State of Connecticut, and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, known collectively as the trustees. The company paid $15 million to restore natural resources throughout the Housatonic River watershed harmed by its activities.

In the last two decades, nearly 50 projects in Massachusetts and Connecticut have been completed under the settlement — protecting habitat, restoring aquatic resources, and improving educational and recreational opportunities.

An undesirable distinction

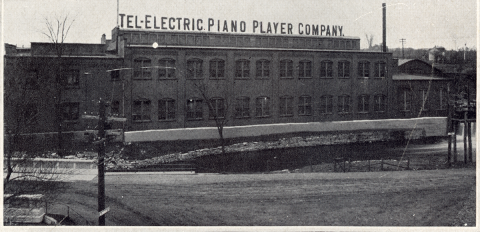

As water flowed over the Tel-Electric Dam, PCB-polluted sediment carried from upstream settled behind it for decades.

“If the dam had failed, contaminated sediment behind it could have traveled downstream, endangering wildlife and people,” said Karen Pelto, project specialist with the Berkshire Regional Planning Commission and retired Natural Resource Damages Program coordinator for the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

In 1999, the Riverways Program, now part of the Massachusetts Division of Ecological Restoration (DER), named the structure one of the state’s ‘top-ten’ unsafe sites.

The designation confirmed what the city already knew: the dam needed to come down. It had been a danger to the community for years, linked to at least one death, and was blamed for chronic flooding upstream.

“It had been on our radar for many years,” said McGrath. “When it was put on the top-10 list, the city agreed, but we knew we’d have to come up with funding.”

The projected price tag? North of $4 million.

Assembling the pieces

Over the next two decades, money came in from local, state, and federal government sources, as well as private and nonprofit corporations. Early on, the GE natural resource trustees approved using settlement funds for the project and eventually gave $870,000.

In 2014, the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation awarded the project a $1.7-million Hurricane Sandy Coastal Resilience grant. Named for the 2012 storm that left the Atlantic Coast reeling from coastal flooding, storm surge, and high winds, the grants were funded by the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) to strengthen the Northeast’s natural defenses — including against inland flooding — in the face of such events.

The Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA) invested a total of $1,550,000 in the dam removal project, including $915,000 from its Dam and Seawall Repair or Removal Program, and $635,000 from DER, DEP, and other grant funds. The remainder of the funding came from the Pittsfield Mills Corporation, the DOI Office of Restoration and Damage Assessment, and the City of Pittsfield.

Significant but not simple

Finally, in 2019, DER and the City of Pittsfield began removing the dam, one of the most complicated such undertakings in Massachusetts history.

“This project illustrates the challenges of and need for climate resilience in urban settings,” said DER Director Beth Lambert. “As part of the dam removal, the project team had to take into account contaminated sediment trapped by the dam, retaining walls, an obsolete railroad bridge, an active railroad bridge, and many other constraints typical of urban environments. While these elements added cost and complexity to the project, addressing these risks helped this project to provide immeasurable benefits to the neighborhood.”

Heavy-equipment operators removed more than 8,000 tons of PCB-contaminated sediment from behind the dam. About 415 dump truck loads went to upstate New York for safe disposal.

A natural and stabilized river channel was built to protect the train trestles, one of which carries daily Amtrak runs across the West Branch. Most of the dam was removed in early 2020, leaving a small portion to support the building. The remnant stands as a monument to Pittsfield’s industrial past and a reminder that it’s never too late to change for the better.

Lessons learned through this site will guide future dam removals and river restoration efforts in Massachusetts and throughout New England.

“This project is a piece of a much larger puzzle in New England, where state, federal, and local partners are working on a landscape scale to restore stream and river ecosystems by strategically removing dams that impede the movement of migratory fish, sediment, and people,” said Audrey Mayer, field supervisor of the Service’s New England Field Office. “As we remove larger and more complex dams, we become more skilled at designing and engineering these projects.”

Thanks to the federal Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Bipartisan Infrastructure Law

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) is a once-in-a-generation investment in the nation’s infrastructure and economic competitiveness. We were directly appropriated $455 million over five years in BIL funds for programs related to the President’s America the Beautiful initiative.

Learn more about Bipartisan Infrastructure Law , the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will put that expertise to good use soon. The legislation, passed in 2021, included $200 million for the Service’s National Fish Passage Program. Six dam-removal projects in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeast received funding in fiscal year 2022. Migratory fish and communities like Pittsfield will reap the benefits of derelict dam removal.

The future looks bright

The West Side neighborhood, where the dam stood, is one of Pittsfield’s most diverse and least wealthy. It is identified as an Environmental Justice community by EEA, based on median household income and racial makeup. Residents of Environmental Justice communities often bear more than their share of environmental burdens.

The City of Pittsfield is trying to flip that paradigm by creating opportunities for local residents to enjoy safe outdoor activities nearby.

“We’re doing this work for the people who live there,” said McGrath. “The dam removal will help draft a new narrative for the neighborhood.”

With the dam gone, its tendency to invite mischief and dangerous behavior is, too. The risk of flooding to people and property during heavy rain events is lessened. And the chance of dam failure sending polluted sediment downstream is nil.

“I’m thrilled and excited about the removal of the Tel-Electric Dam,” said Jane Winn, co-founder and executive director of the Berkshire Environmental Action Team (BEAT), a group formed by Pittsfield neighbors in 2003 to steward the Housatonic and ensure enforcement of state and local environmental laws. “I feel as though, after many years, everything’s coming together.”

Five miles of river habitat upstream of the dam site is now reconnected with the lower portion of the West Branch and, ultimately, the greater Housatonic River. Fish and other aquatic species can once again move freely in the watershed.

“Just a two-minute canoe ride from Wahconah Park is a wild area of the river that should benefit from the connection,” said Winn. “Already, eagles, herons, beavers, and bears can be seen here.”

Following an era of supporting industry and another of sitting idle, the Tel-Electric Dam is no more. Its removal has ushered in an age of community wellbeing and ecological health. That’s change worth waiting and working for ... just ask Jim McGrath.