What does it matter, really, that thousands of miles of river flowing through the middle of Maine have been the subject of years of restoration work? What is behind the fact that the Penobscot is open, unobstructed and free for fish to swim up, past the sites of former dams?

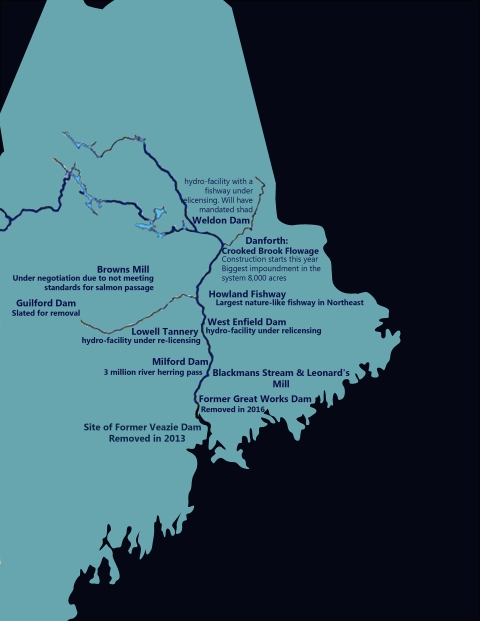

The work spans 20 years, coordinated by an interlocking list of partners so long, so sprawling that I won’t even attempt to name them all here.* Since the 1990s, they’ve removed, restored, remediated and relicensed so many dams that I have spent literal hours working my way up the Maine river on a map, plotting, point by point, the sites of each project (of the 20+ dams in the watershed, 2 have been removed, at least 15 upgraded and restored, and 6 are in the process of evaluation, planning, and construction).

It’s confusing and intricate and winding. But the outcome is clear: 3 million river herring have returned to this once closed-off watershed.

Maybe you already care about river herring; maybe reading that massive number sends a rush of sentiment about the resilience of nature running through you; maybe for you, three million river herring returning to the Penobscot is enough to immediately see that, yes, all the years, all the money, all the people, all the resources dedicated to restoring the river matter.

Or maybe, you don’t even know what a river herring is and are still trying to figure it out why people refer to alewife and blueback herring interchangeably (river herring refer to both migratory fish species, I’ve learned). You might find it interesting that they can once again make the upstream journey from the sea to freshwater lakes and ponds to spawn, but you and I have both made it pretty far in life unaware that, until recently, these small fish have been unable to reach their destinations in the Penobscot.

“An issue with the recovery of a lot of these species is that you speak to the public and say ‘river herring,’ and they look at you like ‘What? What is that? Why do I care?’” said Bryan Sojkowski, a fish passage fish passage

Fish passage is the ability of fish or other aquatic species to move freely throughout their life to find food, reproduce, and complete their natural migration cycles. Millions of barriers to fish passage across the country are fragmenting habitat and leading to species declines. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's National Fish Passage Program is working to reconnect watersheds to benefit both wildlife and people.

Learn more about fish passage engineer with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

So, why care? I've come to care because I now realize that when someone like Bryan says “river herring in the Penobscot,” it’s not just about a small fish — or even three million of them. It’s about the restoration of a natural nutrient flow; it’s about Maine’s fishing and tourism economies; and it’s about an invaluable cultural touchpoint for the Indigenous nation that shares its name, livelihood and land with the river.

It’s also about balancing human needs with the needs of wildlife, as we both adapt to a world that’s continuously shaped by climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change .

Small fish, big implications

I credit Jon Vander Werff, fisheries biologist with Save the Sound, for my new-found appreciation of alewife.

“Alewife are the coolest, most resilient fish there are,” he told me, as we sat on the shores of the now-open West River in New Haven, Connecticut. The site was once blocked by the Pond Lily Dam, preventing alewife and blueback herring from making their upstream trips.

“They [complete the nutrient cycle between ocean and river] by doing all their feeding out in the open ocean. On their in-migration, everything loves to eat them — from birds of prey, great blue heron to raccoons, snapping turtle, other fish, seals, lobster, sportfish like bass, bluefish, tuna, even whale are documented eating them.” He had to pause to catch his breath. “Excuse me, I am getting myself excited. As I should!”

Land managers, biologists and stewards in the Penobscot River watershed share his excitement for river herring. It’s rare, but crucial, that nutrients move back up the river — that's where river herring are invaluable.

But, on the Penobscot, a series of dams blocked upstream passage for river herring — and other sea-run fish, like their flashier ecosystem-associate, the Atlantic salmon. Without alewife, the watershed was missing the crucial transfer of nutrients and suffering for it.

“[Endangered Atlantic salmon] co-evolved with sea lamprey, river herring, all kinds of things. They depend on these other species. In order to have healthy Atlantic salmon, we need healthy alewife, river herring — we can’t do it without doing work that brings back these other species,” said John Burrows, executive director of the Atlantic Salmon Federation’s U.S. programs.

“River herring is a forage species for everything,” Sojkowski added. “Basically [the species] just supports everything. So, in my mind [restoring river herring is] the floor that needs to be done first.”

Big river, big project

The planning, coordination and construction of that floor is a colossal undertaking.

Dams on the Penobscot went up as early as 1834 — often for power generation at mills. They then evolved into today’s hydroelectric dams. When those dams came up for re-licensing under the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), federal and state agencies, the Penobscot Indian Nation, conservation organizations and the dam owners created a formal partnership focused on taking down the barriers these dams presented to fish.

In 2004 — five years after beginning these conversations — the partners formally set out as the Penobscot River Restoration Trust to achieve two goals: maintain hydropower and restore the sea-run fisheries on the river.

By 2016, the group had removed the Great Works Dam and the Veazie Dam — the first hurdles fish encountered coming in from the sea. Then they built a channel that allows fish to migrate around the Howland Dam, further upstream on the Piscataquis River, a tributary to the Penobscot.

When people talk about the Penobscot restoration, it’s the removal and revival of these three dams that they’re likely referring to — a finite project, with an established group of partners.*

Yet, that work only called attention to how much more remained to reach a genuinely open river.

“It’s never just one [dam]. It’s like you scale one mountain, then scale multiple mountains,” said Landis Hudson, executive director of Maine Rivers. True connectivity means removing all barriers.

What followed — and what continues – is a sprawling, confusing, ongoing tag-team of hydroelectric dam relicensing and remediation.

Economic impacts

This is not that the first phase lacked results; it brought about restoration of 2,000 miles of river and stream habitat. It improved access for Atlantic salmon, American eels, other sea-run fish, and, of course, more than three million river herring.

The surge in numbers of migratory fish has been a boon to the economy, locally and regionally.

The lobster industry contributes more than $1.5 billion a year to Maine's economy. As populations of Atlantic herring — long used as lobster bait — have plummeted in recent decades, the industry has looked to rising river herring populations as a readily available substitute.

Small towns along the river also manage most of the commercial fisheries for river herring; each municipal; harvest creates revenue for local priorities like schools and streets.

Of course, beyond lobster, a range of wild marine life eats river herring. They are the “prey base” for a lot of marine ecosystems, Sean Ledwin, director of the Bureau of Sea-Run Fisheries and Habitat for the Maine Department of Marine Resources, told me — other words for Sojkowski’s “floor.”

Investing in this base supports other commercial fisheries — since cod, haddock, and striped bass all also eat river herring — and it directly benefits surrounding towns in Maine, a place with a rich outdoor recreation industry, dependent on thriving ecosystems.

“Maine is sort of a wild tourist destination, where folks like to come and fish and hunt. The marine economy is really important, for folks that live here and for the tourist economy,” Ledwin added.

Each spring, simply the sight of silver alewives rushing up a river becomes a commercial good. Maine towns like Damariscotta and Benton host river herring run festivals on restored rivers to celebrate this surge.

“You hear these stories like, ‘Oh back in colonial times, you could walk across all these fish,’ or ‘Rivers were black with fish.’ With river herring, that actually happens still with these restored runs,” said Ledwin.

Cultural impacts

“Today signifies the most important conservation project in our 10,000-year history on this great river that we share a name with, and that has provided for our very existence,” Penobscot Indian Nation Chief Kirk Francis told "The New York Times"when the Great Works Dam came down in 2012.

On that day, a tribal elder “used an eagle wing to fan smoke from a smoldering smudge of sage, tobacco and sweet grass over the crowd that had gathered to watch,” the Times reported. The scene shows the significance of this act and this ongoing connectivity work.

In the decade since, as river herring stream back up the watershed, the Tribe has been able to run subsistence harvests of the fish, which is a traditional food.

Penobscot Indian Nation biologists have been central to the restoration work from the start, and in the past 10 years, they have focused on restoring Mattamiscontis Stream, a tributary to the Penobscot.

Climate connection

That ongoing work, further up the Penobscot and its tributaries, has gained even more importance as the effects of climate change on species like alewife and salmon — and on the entire river ecosystem — become increasingly evident.

After the removal of the Great Works and Veazie dams, 19 remain, Sojkowski counts. All 19 are still the site of some ongoing work to continue opening the river’s flow to migratory fish.

Whenever those intimate with the Penobscot talk about the water just behind a dam, they don’t call it “river.” They call it an impoundment.

Dams hold back water and let it heat — all this in the context of a river that, even without impoundments, is already heating up due to rising global temperatures.

“River temperatures is definitely a key factor for when these species [like river herring] enter the rivers and when they need to get out,” said Sojkowski, the fishway engineer.

He also works on the Merrimack River, which runs through New Hampshire and Massachusetts. Since 2016, the average length of the Merrimack’s herring run has compressed from 38 days to 17 days.

“To me that’s the biggest factor, but how do you work that into any fish passage design? It is what it is, although the impoundments upstream of these dams are definitely warming faster than the natural river would with moving water,” Sojkowski said.

Burrows, with the Atlantic Salmon Federation, notes that these runs are not just getting shorter, but they’re also moving earlier; the Federation’s data shows the migration happening 10-14 days earlier.

Changing conditions in other rivers — like the Merrimack — underscore the importance of a healthy Penobscot, at the northern, cooler end of many species’ ranges. While river herring are relatively resilient to warmer temperatures — their habitat range extends to Florida — species like salmon and shad will be forced out of warmer river systems and will benefit from an open, cooler Penobscot.

The specific effects climate change will bring to the watershed are still unclear, though it can be clear that there will be changes. “There is a lot of operating in the dark that we’re doing, so the more we can get things back to normal function the better,” Hudson, of Maine Rivers, said. “There’s a whole new ball game with climate change.”

Forging into the Future

"Back to normal” may be a stretch.

Balancing humans’ energy demands and wildlife’s habitat needs will always require compromise (“trade-offs,” as the Natural Resources Council of Maine puts it). Right now, wildlife is taking most of those compromises.

“Reaching runs at historic levels — that's just not gonna happen,” said Sojkowski, “but can we do enough to have a little more balance between the [wildlife] and our energy needs?”

In this era of climate change, hydropower is one of the main sources of low-carbon energy in Maine.

The state has set a goal of reaching 100% renewable energy by 2040, yet still relies on coal, natural gas and nuclear for 75% of its energy.

This is why work on the Penobscot is so delicate, so much more intricate than simply removing dams, and why preserving hydropower capacity has remained a primary goal of the project since its inception. Achieving that goal involves a sprawling, confusing tag-team process of hydroelectric dam relicensing and remediation, which opens the door for hydroelectric companies to work with wildlife managers and provide fish passage.

Many feel the Penobscot work strikes that balance between the needs of wildlife and those of people: “The Penobscot showed that colossal and amazing things are possible with time and patience,” Hudson said.

It is a symbol for providing wildlife habitat alongside energy generation. As the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Bipartisan Infrastructure Law

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) is a once-in-a-generation investment in the nation’s infrastructure and economic competitiveness. We were directly appropriated $455 million over five years in BIL funds for programs related to the President’s America the Beautiful initiative.

Learn more about Bipartisan Infrastructure Law and Inflation Reduction Act open up new streams of funding to support dam removal and repair, the Penobscot is the gold standard. The river continues to undergo further restoration, at upstream dams and sites that have recently come up for review. At the same time, managers on other rivers look to duplicate the project’s success.

“The Kennebec [River’s] restoration was a good model for the Penobscot; now Penobscot will be a good model for other big rivers like the St. Croix,” said Ledwin. “At the St. Croix River, we see even bigger potential for river herring.” That river is now in the early stages of restoration, and a project to install a state-of-the-art fish lift at the Woodland Dam in Baileyville received $2 million from the Infrastructure Law.

“All the time, people say ‘How are we going to pull a Penobscot on this?’” Hannah Mullaly, a fish and wildlife biologist in the Service’s Maine Field Office told me. “It just represents this huge, large-scale project with unparalleled connectivity.”

And it matters to herring and humans.

*I will name the extent of such partners, here:

The Penobscot River Restoration Trust included the Penobscot Nation, American Rivers, Atlantic Salmon Federation, Maine Audubon, Natural Resources Council of Maine, The Nature Conservancy, and Trout Unlimited.

PPL Corporation, Black Bear Hydro LLC, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Indian Affairs, National Park Service, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, State of Maine’s Department of Marine Resources, Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, and the former Maine State Planning Office all have contributed to further restoration work.