In the spring of 2021, nearly three dozen birds, mostly chestnut-bellied seed finches, took off on an unusually long flight.

Native to eastern South America, these small black birds with blunt beaks, beady eyes and chestnut-colored bellies, typically spend their days foraging along the forest edge.

But on a Monday in late April, 35 of them boarded a plane in Guyana headed for John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York.

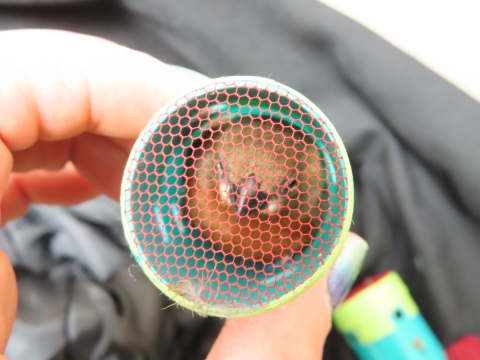

They weren’t traveling in carriers in the cargo hold, as live birds typically do. They were inside the cabin of a commercial airplane, stuffed into plastic hair curlers to prevent them from moving, inside hidden pockets sewn into a bespoke suit. The individual wearing the suit, Kevin Andre McKenzie, was smuggling the finches into the U.S. to sell for singing matches.

Pitch perfect

A hobby and sport common throughout the Caribbean and Guiana Shield of South America — a region that includes Guyana — singing matches are social gatherings where men, primarily, compete male finches against one another in races to sing the most songs.

“The male birds are naturally competitive with their song,” explained Kathryn McCabe, a special agent with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Office of Law Enforcement who investigates the illegal songbird trade. “Whichever one sings 50 pieces of song first is declared the winner.”

Guyanese Americans, and other communities with ties to the Caribbean and Guiana Shield region, have continued this rich tradition, which involves attentively raising and training birds and brings together family, friends and neighbors for weekly matches. It also unites generations. Songbird keeping is often passed down through community members and families, including from father to son or from uncle to nephew.

While it is legal to import these finches into the U.S. with proper documentation, demand for finch species native to South America that are prized for their elaborate songs has led some people to engage in large-scale smuggling. People who buy these finches may not even know they have been brought into the U.S. illegally.

A bird in hand

According to law enforcement officials, hundreds of finches are smuggled into the U.S. each year through JFK alone.

In addition to wanting to bring in large quantities of finches to realize a profit — the birds can fetch anywhere from $500 to more than $10,000 — some sellers have resorted to smuggling in part to avoid the 30-day quarantine requirement for importing them.

That’s because the quarantine process is believed by bird keepers to compromise a bird’s training, which represents a significant investment of time. Training involves raising juvenile birds in a quiet place away from distractions, repeatedly playing them recordings of wild bird song and then socializing birds with friends and members of their families. To some keepers, birds are a part of the family.

Eventually, keepers take their birds on walks in the community to slowly habituate them to other noises without losing the songs they have mastered.

In quarantine, trained finches may be in continuous proximity to other birds, and birdsong, which may dull their competitive edge or unduly influence their singing.

But quarantining can also save their lives.

Birds are one of the highest risk taxa for the spillover of diseases to captive and wild bird populations, as well as humans. Songbirds specifically have been known to spread pathogens such as pox viruses, West Nile disease and avian influenza.

By avoiding quarantine, those who smuggle finches introduce the risk that these birds will transmit diseases from the wild to destination countries. To conceal their activities, they put birds in inhumane, stressful conditions — imagine being stuck inside a shipping tube for hours, unable to move your limbs. Most don’t survive the trip.

In response to this growing problem, the Service’s Office of Law Enforcement, in collaboration with Customs and Border Patrol, Homeland Security Investigations and the government of Guyana, has stepped up efforts to prosecute smugglers who exploit wildlife and create the potential for disease transmission.

Flight risk

Although McKenzie was the one sporting the finch-filled suit, he was a paid courier — his outfit and plane ticket had both been purchased by Insaf Ali, a known leader in the illegal finch trade.

In 2018, a special agent for the Service arrested Ali for smuggling finches into the U.S. He received two years of probation.

In April 2021, one year after Ali’s probation ended, the Service received a tip that someone would be smuggling finches into the U.S. under his direction. That was McKenzie. When he deplaned at JFK, customs agents screened him and found the birds in his suit.

In January 2022, Ali was arrested again at JFK before he boarded a flight to Guyana. Special agents had information indicating he was arranging for another courier to smuggle birds into the U.S. They found two packages of hair curlers in his luggage.

This spring, Ali was sentenced to serve one year and a day in prison for conspiring to illegally import wildlife. It’s the strongest sentence someone has received for finch smuggling to date.

“We take this seriously and we will prosecute those who bring these birds into the U.S. illegally,” McCabe said. “They can be imported legally, and that’s in the best interest of both people and birds.”

Bye, bye, birdie

In addition to screening for diseases, the import process helps keep the finch trade sustainable. Guyana has established quotas to prevent over-collection from wild populations.

But quotas are only effective if they are enforced and people follow them.

Although the most sought-after species — including the large-billed seed finch, chestnut-bellied seed finch and plumbeous seed eater — aren’t considered imperiled, they have become increasingly rare.

Based on the best available information, at least 13 species in the Guiana Shield region that are sought after for the singing-competition trade show evidence of population declines due to trapping. Because most of these species have not been studied in detail or systematically monitored, there is little scientific data on how the trade impacts their population trends.

But anecdotally, McCabe said, “We’ve heard that people are having to go deep into the forest to find these birds.”

A different tune

While stopping serial smugglers is a key part of the response, the Service is also working to address the trade by getting to the root of the problem.

Later this year, the Combating Wildlife Trafficking Branch of the Service’s International Affairs program will launch a new financial assistance program to support work by local organizations in the Caribbean and Guiana Shield to conserve songbird species that are directly threatened by unsustainable or illegal trade. They will also work in North America and Europe to reduce consumer demand and foster a sustainable, legal trade that reduces pressures on wild populations.

The program is part of the Species Conservation Catalyst Fund, an initiative that aims to reduce wildlife trafficking for specific species by looking at their trade in the context of social and ecological systems, from source to transit to destination.

The Service is also working closely with experts in public, animal and ecosystem health to develop comprehensive plans and appropriate responses to disease events, including those associated with the trade in wildlife and wildlife products.

Authorized under the American Rescue Plan, the new Zoonotic Disease Initiative will provide up to $9 million in available funding to states, Tribes and territories to strengthen early detection, rapid response and science-based management research to address wildlife disease outbreaks before they cross the barrier from animals to humans and become pandemics.

The initiative reflects the One Health approach, which focuses on sustainably balancing health outcomes for people, animals, plants and their shared environment, in part by recognizing that they are interconnected.

How you can help

You can play a role in addressing songbird smuggling by reporting wildlife crime.

If you believe you have information related to any wildlife crime, please report it directly to our law enforcement officers: 1-844-FWS-TIPS (397-8477) or https://www.fws.gov/wildlife-crime-tips

When possible and safe to acquire, include screenshots, links, images, location and any other relevant information to help with a potential investigation. Be situationally aware and trust your gut. Do not put yourself in harm’s way to gather documentation of a wildlife crime.