It’s high noon and the bright summer sun blazes in a flat blue sky, not a cloud in sight. A breeze ripples across a small outcropping of blooming flowers, momentarily jostling native bees and butterflies feasting on nectar. You could be witnessing this in a city garden or possibly the beach on a tropical island in the Pacific. Or on the side of the highway in any part of the continental United States. While the dance between pollinators and plants is as ubiquitous as it is timeless, there is more to this idyllic scene than meets the eye.

Though pollinators are essential to our food production and food security, the plants on which they depend have the power to help people in a different way. On public and private lands across the country, a quest for pollinator conservation is also leading to climate solutions. Work happening across the Service demonstrates that caring for the even the smallest insect has the potential to lead to big changes for the planet.

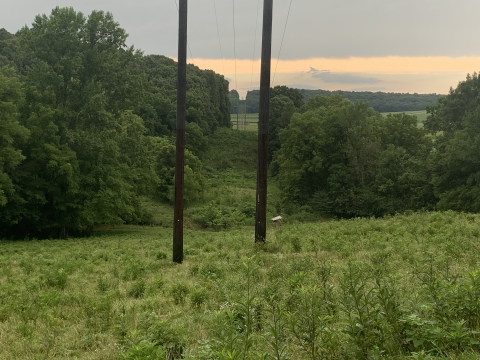

The Highway to Hope

According to the Federal Highway Administration, the United States is crisscrossed with more than 3.9 million miles of roadways. On the edges of these roads, in shoulders and ditches, are unpaved places where pollinators can find food and shelter. Known as transportation rights-of-ways, they represent a conservation opportunity of enormous magnitude in stretches of land most people drive past without ever noticing. The opportunity grows larger when combined with energy rights-of-way, the land that follows overhead powerlines or underground pipelines and is kept clear of woody vegetation for safety and maintenance purposes.

“Native flowers and grasses are able to flourish in these areas,” says Sean Sweeney, a fish and wildlife biologist with the Service.

Sweeney coordinates the programmatic candidate conservation agreement with assurances for the monarch butterfly on energy and transportation lands. Participants who enroll in the monarch agreement voluntarily agree to provide habitat for the monarch butterfly on energy and transportation rights-of-way found across the country.

“To-date, there are more than 850,000 acres nationwide that are currently committed to monarch and pollinator habitat,” Sweeney says. “We expect much more in the near future as well.”

Members of the Rights of Way as Habitat Working Group, led by the University of Illinois-Chicago, hope to reach 2.3 million acres of monarch habitat nationwide. What does all this pollinator habitat mean for climate? In addition to providing food and shelter for pollinators, these lands are drinking in and storing gases that otherwise would enter the atmosphere and trap the sun’s heat, contributing to global warming. The monarch rights-of-way work could potentially lead to the sequestration of between 106 million and 138 million tons of carbon dioxide. Looking to the future, the monarch is only the beginning. The Service and partners are exploring a companion agreement for at-risk and protected bumble bee species.

Picky Eaters and the Need for Seeds

While the rights-of-way work demonstrates a creative and collaborative solution to finding and connecting pollinator habitat across the country, acreage alone is not enough. Conservation success for pollinators starts with a foundation of native plants. When it comes to climate solutions, native plants do the heavy lifting on soil health, sequestering carbon and providing shade cover. In heavily degraded areas, how do we know what native plants to put where during restoration work? The answer: Pollinators have food preferences.

In Hawai’i, the endangered Anthricinan yellow-faced beeis no exception. A medium-size bee that can easily be mistaken for a small wasp, it is found in thin bands of habitat along Hawai’i’s coastline. As the only native group of bees to Hawai’i, Hawaiian yellow-faced bees have co-evolved with many of the state's native plants that depend on the insects for pollination. The special connection between pollinator and plant can be seen with the Anthricinan yellow-faced bee and the 'akoko and ʻākulikuli plants that grow close to the ocean, along rocky and sandy coastlines.

“In general, habitat restoration takes years and sometime decades,” says Dr. Sheldon Plentovich, the Service’s Pacific Islands Coastal Program coordinator. “However, I recently had an experience when I got that rare feeling of instant gratification at work. I was out-planting 'akoko at our Ka Iwi site on Oahu. 'Akoko vanished from this site years ago, so the bees had no prior experience with the plant. Yet while I was there, two yellow-faced bees appeared and started visiting the flowers before I could get a plant from a pot into the ground.”

Biologists found that pollen from 'akoko and ʻākulikuli plants are found in greater abundance in yellow-faced bee nests. When reviewing the presence and abundance of plants in the areas where the bees forage for food, it became apparent that the bees were seeking out certain native plants more so than others in the area. Identifying yellow-faced bees’ favorite foods told biologists what they should plant during restoration efforts.

Knowing what to plant is only part of the challenge. Like the pollinators they support, native plants are also in need. The recent National Assessment of Native Seed Needs conducted by the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine found that the United States doesn’t have the quantity of native seeds and plant materials needed to achieve restoration goals. It is estimated that millions of pounds of native seeds and plant materials will be needed to ensure the success of habitat restoration projects across the country. In the case of the yellow-faced bee, seeds for out-planting efforts were collected onsite or from the next closest population.

When asked about how looking at the restored yellow-faced bee habitat made her feel, Plentovich replies, “It’s extremely satisfying, especially when the work is powered by the community who continue to protect and enhance the site through partnerships with scientists and land managers.”

Climate Oasis for People and Pollinators

In Wilmington, Del., local community sits at the heart of the National Wildlife Federation’s Sacred Grounds Program, which works with congregations, houses of worship, and faith communities to create on-site wildlife habitat and engage members in stewardship activities. Due to rapid development and urbanization, Wilmington is home to an abundance of impervious surfaces, like roofs and pavements, that mean more flooding during intense rainstorms, and more trapped heat during summer heatwaves. This can present challenges to both people and pollinators.

Climate change is already taking a disproportionate toll on Wilmington’s most vulnerable residents. People of color and those with the lowest incomes are more likely to live in neighborhoods affected by flooding, air pollution, and the urban heat-island effect. The city’s youngest and oldest residents are more susceptible to associated health impacts.

With support from the Service’s Delaware Watershed Conservation Fund, the National Wildlife Federation is assisting 20 faith communities in becoming designated Sacred Grounds sites, prioritizing communities most vulnerable to climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change and environmental injustices. Through hands-on technical assistance, mini-grants, and educational workshops, these congregations will install native pollinator gardens on their grounds and engage their communities in environmental stewardship.

The key to the project’s success has been tapping into a network of community partners and leaders. The National Wildlife Federation partnered with Delaware Interfaith Power and Light, Delaware Nature Society, Delaware Center for Horticulture, and Interfaith Community Housing of Delaware to understand the needs of congregations and congregants.

“It started with asking what they want,” says Grant LaRouche, director of conservation partnerships for the National Wildlife Federation in the Mid-Atlantic. “It grew into a passion among our partners for creating these pollinator habitats and a pollinator corridor in Wilmington.”

The gardens will support more than just pollinators. They will serve as places of peace and celebration while creating a more resilient Wilmington. Native plants have strong root systems that absorb and filter water and stabilize soil. Collectively, the 20 300-square-foot pollinator gardens that will result from the project will mitigate flooding, erosion, and polluted runoff in these neighborhoods. They will also work to reduce the urban heat island effect by lowering surface temperatures instead of absorbing and re-emitting the sun’s heat like pavement does. According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, trees and plants help cool the environment, making solutions like pollinator gardens a simple and effective way to reduce the temperature in urban heat-islands.

From highways to the Pacific islands to church gardens and beyond, pollinator conservation and climate solutions can be found walking hand-in-hand. With pollinators living on every continent save Antarctica, there are opportunities to help pollinators, and in turn combat climate change, wherever you live. On the road to saving some of the world’s smallest inhabitants, we just might find ourselves saving the planet, too.

Katie Steiger-Meister, Science Applications, Headquarters

Contributing: Bridget Macdonald, Office of Communications, Northeast Region