Native Hawaiians, as the original stewards of Hawai‘i, developed substantive knowledge and a reciprocal connection with their environment. This way of knowing and relating to their surroundings is perpetuated within Native Hawaiian community, identity, language, and traditions. Spanning centuries and continuing today, Native Hawaiian interactions with plants and wildlife, including forest birds is informed by reverence, respect, and responsibility. And demonstrated in the actions of appreciation and care extended to forest birds as family members, ancestors, and guardians.

Through ‘ike ku‘una (traditional or inherited knowledge), the kumulipo (cosmological and genealogical chants), hula (the indigenous dance of Hawai‘i), and ka‘ao (traditional stories), Native Hawaiians are intimately connected to forest birds, their immediate habitat, and their broader island and archipelagic environment.

This kinship increases the urgency to save four endangered species of Hawaiian honeycreepers from imminent extinction caused by climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change and other human caused factors. Once, there were more than 50 species of honeycreepers spread across Hawai‘i – today, only 17 species remain, with a few species having less than 200 individuals remaining. Rapid population declines have now pushed the ‘akikiki, ‘akeke‘e, kiwikiu and ‘ākohekohe to the brink of extinction.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) is using the best-available science to adapt to and mitigate for climate change impacts on the natural resources we are entrusted with managing. Science informs our understanding of climate change risks, impacts, and vulnerabilities. The Service’s recognition that biological resources are cultural resources, is also expanding opportunities for engagement with the Native Hawaiian community.

Climate Change Impact

Climate change is having profound impacts on our nation’s wildlife and plants, and their habitats. Climate change is a threat multiplier. It amplifies threats to wildlife and ecosystems from issues such as habitat loss, disease and the spread of invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

Learn more about invasive species . This amplification makes the effects of these threats even more damaging.

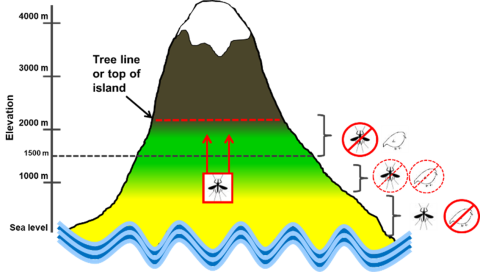

Avian malaria, spread by non-native mosquitoes, is currently the main threat to Hawaiian forest birds. Climate change has increased temperatures in high-elevation forests, allowing mosquitoes to reach areas that were once malaria-free. A single bite from an infected mosquito can kill a bird, and the death rate may exceed 90 percent for some bird species. As a result, many threatened or endangered native birds now only survive in high-elevation forests where mosquito populations and malaria development are limited by colder temperatures. Unlike continental bird species, Hawaiian forest birds cannot move northward in response to climate change or increased disease stressors, but instead must adapt or move to less hospitable habitats to survive.

As climate warms and more mosquitoes move up the mountainside, higher elevations have become areas of disease transmission and no longer provide a haven for the most vulnerable species. The rate of disease infection is likely to speed up as the numbers of mosquitoes increase and more diseased birds become hosts to malaria, continuing the cycle of infection to healthy birds.

Working Together to Save the Birds

There is hope for the birds, but natural resource managers are fighting the clock to implement management actions to protect these unique species from further decimation. In spring 2022, a report authored by the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), the Service, and U.S. Office of Native Hawaiian Relations (ONHR) and published by the University of Hawai‘i at Hilo’s Hawai‘i Cooperative Studies Unit used input from a wide range of biologists and biocultural experts to develop scientifically backed community-supported strategies to prevent the extinction of Hawaiian forest birds. In the report, the ‘akikiki, ‘akeke‘e, kiwikiu, and ‘ākohekohe were identified as being at risk of extinction in the next one to 10 years, with 12 more species at risk of extinction over a longer time period due to climate-facilitated expansion of mosquitoes.

Based off the results of the spring 2022 report, in December 2022, the Department of Interior (DOI) published a strategy for preventing the extinction of Hawaiian forest birds. In June 2023, Secretary Haaland announced the effort would be a Keystone Initiative under President Biden’s Investing in America agenda, pledging nearly $16 million of DOI funds to help implement the strategy.

“Hawaiian Forest Birds are a national treasure and represent an irreplaceable component of our natural heritage. Birds like the ‘I’iwi, Kiwikiu and ‘Akikiki are found nowhere else in the world and have evolved over millennia to adapt to the distinct ecosystems and habitats of the Hawaiian Islands,” said Secretary Deb Haaland in the announcement. “Thanks to President Biden’s Investing in America agenda, we are working collaboratively with the Native Hawaiian Community and our partners to protect Hawaiian Forest Birds now and for future generations.”

The strategy outlines five objectives. The objectives with progress updates are summarized below:

1. Develop and deploy Incompatible Insect Technique (IIT) to reduce the mosquito vector of avian malaria by 2026.

Wolbachia IIT, is a form of mosquito birth control that can suppress mosquito populations at a landscape level and that, if successful, could effectively break the avian malaria disease cycle.

In October 2023, the Service and State of Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources (DLNR) met their respective, National Policy Act and Hawai‘i Revised Statutes Chapter 343 environmental requirements to move forward with employing IIT to reduce mosquito populations within approximately 59,204 acres of forest reserves, state parks, and private lands in the Kōkeʻe and Alakaʻi Wilderness areas of Kauaʻi. This effort is consistent with the statutory missions and responsibilities of DLNR and the Service and seeks to protect birds from mosquito-borne diseases in key higher-elevation native forest bird habitat. The multi-stakeholder project would raise and sequentially mass-release male mosquitoes that carry a strain of Wolbachia that is incompatible with wild females, causing eggs to be infertile. Extensive pre- and post-release monitoring would be implemented to monitor the effectiveness of releasing incompatible male mosquitoes on the wild mosquito populations. A similar IIT mosquito control project by the National Park Service and DLNR on Maui began in fall 2023.

Over the next five years, the goal is to implement Wolbachia IIT at high-elevation sites in East Maui and Kauaʻi and to complete the planning necessary to implement the technology at either Hakalau Forest National Wildlife Refuge or Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park. The Service is working as part of a multi-agency partnership, along with Birds Not Mosquitoes, to help develop, assess, and implement Wolbachia IIT as a conservation tool across Hawai‘i.

2. Establish captive care programs for bird species most at risk of imminent extinction by 2026.

Captive care involves removing forest birds from the wild and placing them in a controlled facility under human care. Long-term captive care can allow for birds to be bred in order to prevent extinction or to supplement wild populations. Short-term captive care can allow for holding of birds until they can be moved to safer forests or released back into the wild once their habitat is disease free following the application of Wolbachia IIT mosquito suppression.

The Service is currently partnering with the State of Hawaiʻi and the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance to manage captive flocks of ‘akikiki and ‘akeke‘e and several kiwikiu individuals. Partners plan to establish a captive flock of kiwikiu and bring in a few ‘ākohekohe individuals into captive care in the near future.

3. Identify species that are appropriate for conservation introduction and implement movement to higher elevation refugia on Hawaiʻi Island by 2030.

Conservation introduction is the intentional movement and release of a species outside its indigenous range for the purpose of conservation. For forest birds, conservation introduction could occur via the movement of individuals from their current range to a suitable, disease-free site on Hawai‘i Island.

No decisions have been made as to whether or not conservation introduction will be an appropriate management strategy for any of the forest birds. However, partners are currently working to assess the feasibility for conservation introduction of ‘ākohekohe.

4. Develop and deploy next-generation tools by 2032.

Although Wolbachia IIT is considered the technique most likely to control mosquitoes using available technology, more effective and/or cost-efficient tools are on the horizon that may be developed to help in the conservation of Hawaiian species. For example, USGS is currently investigating genes and microbes that may be associated with heightened immunity and evaluating approaches to develop tools such as vaccines and probiotics to help protect sensitive species from avian malaria. These tools may allow for birds to coexist with malaria where mosquitos are difficult to control.

Other examples of next-generation tools could include gene drives or precision-guided Sterile Insect Technique.

5. Develop and implement conservation strategies informed with Native Hawaiian biocultural knowledge and deployed with appropriate protocols and cultural practices (immediately and throughout strategy implementation).

Hawaiian forest birds are an integral ecological and cultural component of the Hawaiian Islands. These birds reflect the health of forests and represent cultural connections between the Native Hawaiian community and the islands. The loss of these species compromises the integrity of unique ecosystems, as well as the natural and cultural heritage of Hawaiʻi. And for the Native Hawaiian community, such a loss is profound and equivalent to the loss of a beloved family member that future generations may never know.

As part of synthesizing opportunities and risks associated with various potential management actions for endangered Hawaiian forest birds, specialists in Hawaiian forest bird biology and biocultural practitioners from the Native Hawaiian community shared their individual experience, knowledge, and cultural viewpoints.

The group of specialists highlighted the relationship of Native Hawaiians to place and to all the things that exist in that space (habitat/ecosystem); when one element or variable is removed from the whole, the relationship is strained. For this reason, some participants expressed opposition to the idea of relocating captive birds to sites outside of Hawai‘i, as this would break the birds’ connection to Native Hawaiians, place, and habitat. However, many advisors accepted conservation introduction and captive care as temporary options to protect forest birds from immediate threats with the condition that Native Hawaiians are allowed to participate and appropriate cultural protocols are observed and supported. The group also highlighted potential ideological differences between preventing the extinction of birds at all costs and respecting cultural views that extinction may be preferable to severing cultural connections and quality of life by removing birds from their birthplace.

Native Hawaiian biocultural knowledge will continue to be woven throughout the implementation of the Hawaiian forest bird strategy.

(Eben Paxton, research ecologist with U.S. Geological Survey, provided support for this article.)