On the morning of July 18, 2024, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's Southwestern Native Aquatic Resources and Recovery Center (SNARRC) in Dexter, New Mexico, received a welcomed addition to the facility with the arrival of 559 wild federally endangered woundfin. The fish arrived on a flight from Hurricane, Utah, on a Utah Division of Wildlife Resources (UDWR) plane. These wild woundfin joined the captive population at the center with the goal of increasing genetic diversity and adding numbers to the broodstock broodstock

The reproductively mature adults in a population that breed (or spawn) and produce more individuals (offspring or progeny).

Learn more about broodstock or breeding adults.

Woundfin are only found in the Virgin River in southern Utah, Nevada, and northern Arizona. The species has had a tough go, as it was originally listed as endangered more than 50 years ago in 1970 under what was then the Endangered Species Conservation Act. Woundfin was then listed under the Endangered Species Act when it was enacted in 1973. Fast-forward to today, and woundfin are dealing with new challenges, leading to more hurdles to overcome.

"Addressing the threat of nonnative fish has historically been the largest hurdle, but after around 25 years, we successfully removed red shiner from Utah and much of the Arizona portions of the river in 2021," said Steve Meismer, Local Coordinator for the Virgin River Program (VRP). "The next step is to address limiting factors, typically water temperature and minimum flows. One of the largest challenges with woundfin is that we are trying to do a lot with a little bit of habitat. As a result, we are looking to see if we can stock into other locations in the basin to see if we might be able to expand the range outside of the historic area while not affecting the communities."

Giving Woundfin a Genetic Boost

SNARRC has housed woundfin at the facility since 1979, with an initial population of 240 individuals. Over the next 25 years, there would be periodic augmenting, adding fish with different genetics to the captive population. The last augmentation of the captive population would happen in 2004.

"Adding wild-caught individuals to a captive population is critical in supplementing the population with genetic diversity," said Wade Wilson, Center Director at SNARRC. "At SNARRC, woundfin naturally spawn in our ponds with the addition of stone substrate to the bottom of the pond. During that spawning period, not every individual will spawn and pass their genetic information to the next generation. This also happens in the wild, and the type of genetic information lost differs between the wild and the captive populations, so they start to become genetically different over time. Adding wild individuals mitigates this divergence."

A Race Against Time

The successful operation of transporting the woundfin from southern Utah to SNARRC was a race against time from beginning to end. With one of the warmest weeks of the summer occurring, woundfin would be concentrated in schools, making capture possible. However, it was also the start of monsoon season, leading to an increase in the frequency of storms that would increase turbidity and cool the river. This would lead to the woundfin to disperse, making capture in any sort of large numbers difficult.

Over two days, a UDWR crew from the Washington County Field Office went to the river to collect fish using a seine, a net that hangs vertically in the water with floats at the top and weights at the bottom edge, the seine is pulled downstream for 10 meters then toward the bank to corral fish. This method was chosen as it minimizes stress put on the fish during capture.

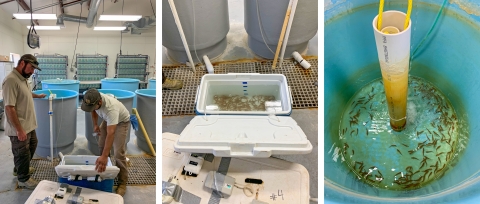

On day one, they were able to capture 314 woundfin. On day two, the number would increase by 245 fish, leading to the final total of 559 woundfin, surpassing their original goal of 500 fish. The captured fish were collected in hand-held coolers and driven to the Washington County Water Conservancy District's Water Treatment Facility (WCWCD), where a temporary holding tank was set up.

The following morning, it was time for the flight. UDWR staff spent the early hours prepping the fish for transport. The fish were loaded into aerated coolers and onto the plane, flown to Roswell, New Mexico, and then driven 20 miles to their new home. At SNARRC, the woundfin were placed in quarantine tanks before being added to the existing population, where they will play a vital role in the recovery of the species.

"Each of our captive populations is considered a refuge population that acts as a genetic reserve should the wild population decline or go extinct," said Wilson. "The woundfin program uses the refuge population as broodstock to spawn new individuals in the spring-summer that are then tagged with Visible Implant Elastomer (VIE, injected colored silicone marks) and stocked back into the Virgin River two years later in the spring. The VIE mark allows fish when captured, to be identified as stocked versus wild."

Partnership in Action

Having a plane for transport was a vital aspect of the operation's success. It is a 15-hour drive, one way, to where woundfin are found. Transporting fish causes stress, making it difficult to keep all of them alive. Reducing the amount of travel time, as well as other stressors such as heat, helps ensure a higher survival rate. While the typical protocol for transport would be the use of a fish transport truck with fish culture staff operating it, the rarity of wild woundfin being captured prompted biologists to seek alternative transport.

This operation shows the impact of working together to support a listed species. Multiple organizations came together, playing key roles, from permitting and logistics to the physical operation to the eventual arrival of woundfin at SNARRC. Each step along the way made a difference and will hopefully lead to a brighter future for a species that needs our help.

"This project faced many hurdles," said Melinda Bennion, Washington County Field Office Project Leader for UDWR. "We hadn't been able to collect enough adult woundfin in 20 years. We'd never held woundfin in a temporary holding facility. We had never flown woundfin. It took a lot of moving parts and a lot of people from hatchery to finance folks, helping to coordinate this transfer of endangered fish across state lines. In the end, the stars really aligned for us on this project, and things couldn't have gone smoother, and that was due to the partnerships and relationships built and the support of the VRP, WCWCD, UDWR, Utah Department of Natural Resources, and Wahweap Warmwater Fish Hatchery and SNARRC. This project was a great example of why partnerships are imperative for the recovery and conservation of native species."