How did you first learn about gar?

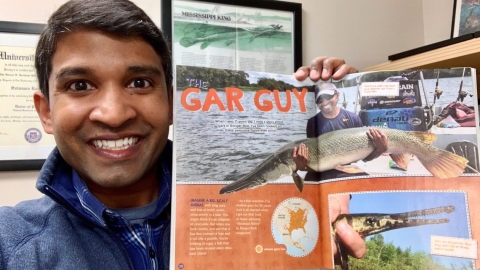

I was always interested in dinosaurs. If you think of prehistoric animals, of course dinosaurs come to mind, but gars have been around since the late Jurassic period. I first saw a gar in an issue of Ranger Rick. I was about 11 years old, flipped to the middle, and saw this fish that looked like an alligator with fins. It had this really primitive, ancient look to it. And I thought “wow, this is really cool.”

It was an alligator gar. I read everything I could about that group of fish — the gars. It really just captivated my attention and imagination during that time. Luckily, I circled back by the time I got into grad school and was able to study gars for my master’s and dissertation research. I’m still chasing my childhood fish fascination today.

How many different gar species are in the U.S.? Where are they found?

There are only seven gar species alive today, but there were more earlier in the fossil record. Today, they’re found from southern Canada all the way down to Costa Rica, and mainly in the eastern half of the United States. Gars used to range into Africa, Asia, and Europe—what we call a Pangeaic distribution.

Can you remember the first time you came across what you might consider a “mega” gar?

Definitely. I was a graduate student at the University of Michigan. I went to New Orleans for a conference about gar. Dr. Allyse Ferrarahadput together a symposium. I was excited to meet a bunch of people who were studying gar, including agency folks from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries. At the end of the conference, Dr. Ferrara and her grad students said, “Hey, we’re heading back to Thibodaux to do some field work…you interested in joining?”

They said, “We’re going to be sampling alligator gar.” And I was like, “WHAT?!?” I quickly got on a computer, changed my flight, and made sure I could be part of that.

It was January 2009. Another guy from Canada and I were like the northern gar guys down there. And we willed them to be caught. We were like, “We need to see these alligator gars.” Sure enough, we got one that was just under five feet long.

Man, I mean seeing an alligator gar for the first time in the wild…that’s definitely imprinted on my memory. And it was at this small university in southeastern Louisiana. In 2017, a job opportunity came up there and now I’m down here working on gar alongside Dr. Ferrara and other researchers at Nicholls State University.

The alligator gar is the largest gar species alive today. As far as I know, it’s the largest even compared to fossil gars. They can easily get up to eight feet long; maybe even close to 10 feet historically, but we don’t have great records of that. They can weigh over 300 pounds.

I often describe them as “alligators with fins instead of legs,” but gars have actually been around longer than alligators. So I think we should be calling alligators “gars with legs instead of fins” if we want to be fair to who came first.

They’ve got these diamond-shaped armored scales covering their body and their face is extremely bony. That long snout is filled with lots of sharp conical teeth.

In addition to their size, one of the things that makes them successful is that they’re air breathers. Not a lot of fish do that. It allows them to persist in environments where more conventionally respiring fish can’t. They’ve also got armor-plated ganoid scales made up of a material very similar to the enamel on our teeth.

They’re coming with the “gar-mor” as we like to call it. These traits in combination have helped them be successful for such a long time — over 150 million years.

Can you tell us more about the scales? What are the advantages and disadvantages?

They’re not quite impenetrable, but that tough hide is very difficult to get through if you’re a predator. The scales are interlocking — almost like chain mail. With that comes a bit less flexibility compared to fish with ctenoid or cycloid scales. Gars may not be able to turn on a dime, but they’re much more flexible than we give them credit for — they can manage a little S-curve or C-shape bend.

They’ve got poisonous eggs, right? Is that unique to gar and what about them makes them poisonous?

The short answer is: we don’t know exactly what makes them poisonous. Dr. Gary Lafleur and his lab down here at Nicholls State have been looking at gar eggs and trying to determine the specifics of their toxicity. I think a study that came out in 2020 that determined it might be a particular phospholipid. But we don’t know if it’s bacterial-based or if the fish are producing it (this would be extremely rare). What else is unusual is that bowfin — the closest relatives to gars — have edible eggs (these two groups are still separated by a decent chunk of time between divergence).

What’s also interesting about gar egg toxicity is that they’re toxic to mammals, birds and invertebrates, but not to other fish or some reptiles. You would think if your eggs are going to be toxic, why not have them be toxic to the animals you’re sharing the environment with? Gars spawn in relatively shallow water that’s extremely warm. Our working hypothesis is you don’t find those conventionally respiring fish there (like bluegill or other egg predators), but you do find crustacean predators like crawfish. And water birds. So we think maybe that’s how that toxicity might have evolved. Humans: don’t eat gar eggs. You’re going to get violently ill.

What challenges are gars facing?

One of the big threats is definitely habitat loss. As we’ve dammed rivers and leveed in certain sections of flood plains, we’ve cut off gars from their spawning areas. That’s caused issues with their population—just like with paddlefish, sturgeon, and other migratory fishes that need access to floodplains and to spawning grounds. It’s a plight of a lot of freshwater fishes.

There’s also this idea that gars eat game fish. In most cases that’s just not true. Gars are predators — they’re going to eat what’s most abundant. In many cases they’re eating shad and other forage fish. In some cases it’s panfish or game fish but, if that’s what’s most abundant in the system, we need predators to maintain balance in any given fish community or the broader ecosystem.

I think that lends itself to the poor reputation of gars. I say they’ve had a historically bad reputation, but really, if you go back further in time, Native Americans and other indigenous people used to eat gar. They still eat gar. They make jewelry and arrowheads out of the hides. They were much more highly utilized. Then, when we think of a more colonial perspective, different fish took a higher ranking. I think it’s a matter of perspective with how gars have been treated over the years. Now we’re trying to improve that reputation, showing they have value as food fish, bring balance to ecosystems, and even recently showing they have value for genomics work and potentially for biomedical research.

You mentioned they need floodplains to spawn.

A lot of times we think of these longitudinal migrations, right? We think of salmon swimming upstream to the spawning grounds. And some gar species do something similar—longnose gar in some areas do leave the mainstem river and swim into the tributaries. But further down south, alligator, longnose, spotted, and shortnose gars perform lateral migrations. When water levels rise in the spring, gars move out onto the floodplains. They take advantage of that seasonal floodplain inundation. It allows them to use additional habitat for spawning, feeding, and nursery areas.

In some areas, alligator gars will actually use inundated terrestrial vegetation to lay their eggs. The adults then eventually move off the floodplain and back into the mainstem. So in some rivers, alligator gars actually require floodplain inundation to successfully spawn. In other areas—coastal environments—they may not be as dependent on that.

It’s really the population level that’s important when we’re thinking about conserving these species. We modify and regulate rivers for different purposes. Obviously where people live we don’t want those areas to be flooded. But where we can return rivers or floodplains to more natural cycles of inundation, that’s beneficial for fish, and also for water birds and other wildlife.

Learn about the other gars!

New episodes of Fish of the Week! every Monday!

We honor, thank, and celebrate the whole community — individuals, Tribes, States, our sister agencies, fish enthusiasts, scientists, and others — who have elevated our understanding and love, as people and professionals, of all the fish. In Alaska we are shared stewards of world-renowned natural resources and our nation’s last true wild places. Our hope is that each generation has the opportunity to live with, live from, discover and enjoy the wildness of this awe-inspiring land and the people who love and depend on it.