Our public lands are rich in history, holding the keys to understanding what life was like for those who came before. Across the Northeast, many national wildlife refuges share a history of resistance, self-determination, and the fight for freedom that is Black History.

At Great Dismal Swamp National Wildlife Refuge in Virginia, the swamp served as a place of relative safety and a potential route for enslaved people seeking freedom. Archaeologist and professor Daniel Sayers initiated a study in 2001 to uncover “maroon” communities in the swamp, which were established by some who hid there. “Maroon” is from the Spanish word cimarron, meaning fugitive or runaway. Different historians estimate that between 2,000 and 50,000 freedom seekers lived in the swamp, originally about 10 times larger than its current 190 square miles.

You can learn more about maroon communities by visiting the Underground Railroad Education Pavilion that has been opened at the refuge. Great Dismal Swamp was also the first refuge named to the Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Program by the National Park Service in 2003.

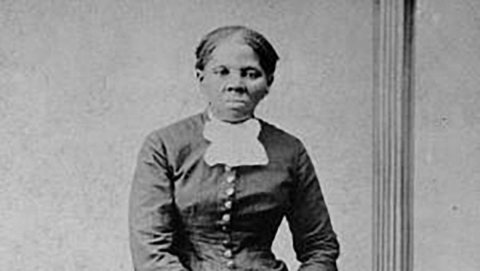

The birthplace of Harriet Tubman was in and around an area that is now Blackwater National Wildlife Refuge in Maryland. The refuge plays an important role in the management and protection of the historic landscape that formed the life and experience of the American hero, who risked her life to help many enslaved escape to freedom through the Underground Railroad.

A remarkable discovery was made on the refuge in 2021: the homestead of Ben Ross, Tubman's father, which he received when he was released from slavery.

During the 1800s, Bombay Hook Island and its surrounding marshes were located on one of the more significant routes of the Underground Railroad. Freedom seekers from the Delmarva Peninsula often made their way through the communities of Dover and Smyrna, where enslaved people were ferried to New Jersey in small boats that were hidden in the Delaware marshes during the day and rowed out under the cover of darkness. Recent scholarly research suggests that these voyages embarked from the marshes between Bombay Hook Island and the mouth of Little Creek, on the eastern shore of Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge.

An area that is now in the western section of Bombay Hook National Wildlife Refuge was part of the Whitehall Plantation, the largest plantation worked by enslaved labor in Delaware. At the end of the 1700s, the plantation was owned by a Philadelphia lawyer, Benjamin Chew. The enslaved members of the Whitehall community engaged in various forms of resistance, which led to a rebellion at Whitehall. The story of the rebellion is richly documented through a series of letters between the Chew family and the enslavers.

A 2013 acquisition to Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge conserved 38 acres in Haddam Neck, Connecticut—including the homestead of Venture Smith, an enslaved parson who earned freedom for himself, his family and several others in the late 1700s. In 1798, Venture narrated his life story, noting that he owned over 100 acres of farmland and three houses. Until his death at the age of 77, Venture and his family lived in Haddam Neck, supported by farming, fishing, lumbering, and river commerce.

The Service supports the preservation of this history through other means as well. With funds authorized by the Endangered Species Act, the Service helped the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department acquire and preserve “Journey’s End,” the homestead of Alexander and Daisy Turner, a family that came up the Underground Railroad all the way to Vermont. Once acquired, the land will become part of a new wildlife management area wildlife management area

For practical purposes, a wildlife management area is synonymous with a national wildlife refuge or a game preserve. There are nine wildlife management areas and one game preserve in the National Wildlife Refuge System.

Learn more about wildlife management area .

Preserving cultural history is of great importance on Service lands. While visiting our lands and national wildlife refuges during Black History Month and throughout the year, be sure to learn about the cultural history these wild places conserve. Find a national wildlife refuge near you.