“Oo, ghee, dot, lee”

“Close! You have to put your tongue on the roof of your mouth when you pronounce the ‘tl’ sound, like you are going to make a clicking noise”

“Ugiidatli?”

“That’s it! You’ve got it, just keep practicing and it will start to feel natural.”

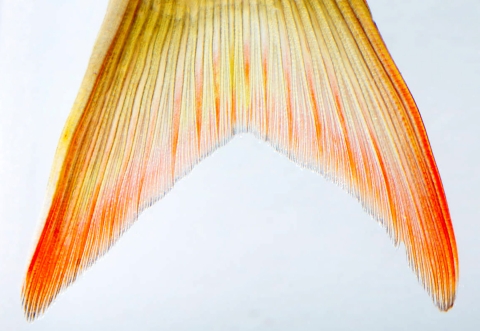

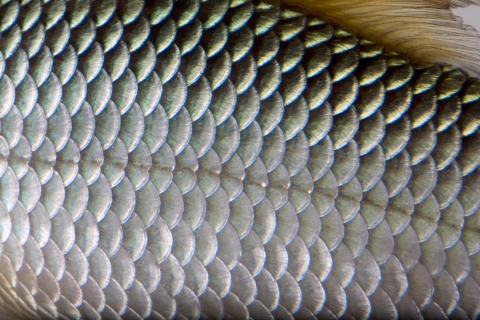

If you’re familiar with this fish, chances are you know it by its English name: Sicklefin Redhorse. Although this stout sucker is neither red nor a horse, the descriptor “sicklefin” goes a long way toward distinguishing this species from other redhorses.

According to Mike LaVoie, the Natural Resource Manager for the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians,

“This great, long falcate dorsal fin that just kind of sets it apart from all the other redhorse in the world...”

The Cherokee name for this fish—Ugiidatli—also draws attention to the unique dorsal fin, translating roughly to “wearing a feather.”

Caleb Hickman, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation and supervisory biologist with the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians explains,

“It’s one of the few fish that has that dorsal fin on top of it kind of looks like a feather. And so that's the idea behind identifying this one compared to other redhorse in our area.”

Recognized as a unique species by the Cherokee people for centuries, the fish only became known to the scientific community in 1992 and wasn't formally described as Moxostoma ugidatli until 2025 (Jenkins et al. 2025). Now, efforts are being taken to conserve both this unique fish and the Indigenous culture to which it is distinctly tied.

Compared to other redhorse species, which can have extensive ranges, the Sicklefin Redhorse is found in only a few river systems, including the Hiawassee and Little Tennessee, in southwestern North Carolina and northern Georgia. Ugiidatli are potamodromous, meaning their spawning migrations occur entirely in freshwater. Adults spend much of their lives in large rivers and reservoirs but migrate upstream to smaller reaches and tributaries each year to spawn. Several species of redhorse can cohabit the same river system, and even utilize the same ideal spawning habitat. However, they arrive at the spawning grounds at different, predictable times and thus don’t have the opportunity to interbreed.

These predictable spawning runs, as well as the large size of the fish (which can reach two feet in length), made redhorses an important source of food for Indigenous people in the region. Some even referred to these suckers as the “salmon of the south” because of their cultural, ecological and size similarities to Pacific salmon. The Cherokee people established town sites on rivers to easily access fish and water, and built fish weirs to aid with harvest. Some are still visible today in these mountain rivers, echoing to a time when redhorses comprised a significant portion of the diet of the Cherokee people.

Caleb explains,

“Cherokee folks along with other southeastern Tribes were often considered river Tribes. Even today, I still talk to people that can tell you stories about different ways of preparing redhorse…They were a predominant food source. Even today, people still eat them. But it's a lot less important in the diet. We are really interested in reintroducing people.”

Today, the Ugiidatli is not as abundant as it used to be, nor does it hold the same cultural significance to many Cherokees as it once did, according to Caleb.

Barriers to migration (namely dams) are a major issue for this fish, and fish in general.

“All rivers are considered what a lot of Cherokee folks would kind of translate to the "long man", where the head is at the headwaters,” said Caleb. “If you disrupt the body, you're cutting off the circulation, the lifeblood of the tribe and all the organisms.”

Many of the dams across the traditional homelands of the Cherokee people, including Ela Dam which obstructs the Oconaluftee River in Swain County, North Carolina, were built before the importance of fish movement and migration was recognized. Now that these dams are reaching the end of their utility as sources of hydropower, discussions are beginning to be held about their future, with the future of redhorse also in mind.

Mike LaVoie noted that he was hopeful for the future:

“We recently passed a resolution that supports us as a division to start to partner and start to look at what dam removal could look like – and we’ve had some productive conversations.”

And there is other work being done to turn the tide for these fish. Since its recognition by the scientific community, much effort has been put forth to study and conserve Ugiidatli. Petitioned for listing under the Endangered Species Act in 2005, Sicklefin Redhorse was kept off the list in large part because of a partnership between the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the US Fish and Wildlife Service, state agencies of North Carolina and Georgia, and several other public and private partners.

Together, they’re working to understand the life history of Ugiidatli, as well as identify the current and historic range of the species. Sicklefin Redhorse have been propagated in hatcheries and stocked into the wild to supplement current populations and re-establish populations in rivers where the fish used to be. In 2015, this network was formalized as the Sicklefin Redhorse Candidate Conservation Cooperative with the goal of proactively ensuring the fish doesn’t reach the point of being in danger of extinction or likely to become endangered.

To Caleb, efforts to conserve Ugiidatli expand beyond the fish to the greater Cherokee culture and language. Notes Hickman,

“Even though we have over 400,000 members, there’s less than 2,000 native speakers left,” making Cherokee an endangered language.”

To preserve this language, Caleb and other Cherokees are working to document as many Cherokee words as possible and encourage their everyday use. Ugiidatli is a prime example of such a word, only recently passed through the official Cherokee Language Consortium.

Beyond conserving the language, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indian’s Natural Resources Department is also seeking to draw people’s attention back to the native species that supported indigenous peoples for millennia. Over the last century, native suckers like the Sicklefin Redhorse have not received the same reverence from anglers on Cherokee lands as more frequently targeted Centrarchids (sunfishes) and Salmonids.

Although the Ugiidatli may be of conservation concern, other, similar species including the Black Redhorse and Golden Redhorse are still thriving in local waterways. Thus, Caleb, Mike, and their team intend to use these related species to hook people’s interest through events like fish fries. They hope that such events will provide an opportunity for people to connect directly with common species while also providing a platform to discuss the conservation issues surrounding rarer species like Ugiidatli.

One of the biggest factors determining the Sicklefin Redhorse’s continued survival is simply having people recognize and care about it. If you want to support the Ugiidatli, talk about it. Impress your friends by correctly pronouncing the Cherokee name. Maybe even plan a trip to the southern Appalachians to appreciate this fish for yourself, dancing feather-like dorsal fin and all.

Reference

Jenkins, Robert E., Favrot, Scott D. Freeman, Byron J., Albanese, Brett and Jonathan W. Armbruster. 2025. Description of the Sicklefin Redhorse (Catostomidae: Moxostoma). Ichthyology & Herpetology, 113(1):27-43.

><> ><> ><> ><> ><>

We honor, thank, and celebrate the whole community — individuals, Tribes, States, our sister agencies, fish enthusiasts, scientists, and others — who have elevated our understanding and love, as people and professionals, of all the fish. In Alaska we are shared stewards of world renowned natural resources and our nation’s last true wild places. Our hope is that each generation has the opportunity to live with, live from, discover and enjoy the wildness of this awe-inspiring land and the people who love and depend on it.