On more than six million acres in Maine and Canada, J.D. Irving, Limited, manages a diverse forested landscape that produces timber for construction, wood chips for glossy newspaper inserts, and wood pellets for fuel. It also supports a majority of habitat for the Furbish’s lousewort.

The company counts this rare plant, which is known only from the banks of the Saint John River, among its natural assets.

“It’s an honor really,” said Kelly Honeyman, Irving’s chief naturalist. “What other forestry company can say they protect more than half of the habitat for an entire species?”

A species with national distinction, no less. The Furbish’s lousewort was one of the first plants listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Act in 1978.

Now four decades later, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is changing the species’ status from endangered to threatened.

Perseverance

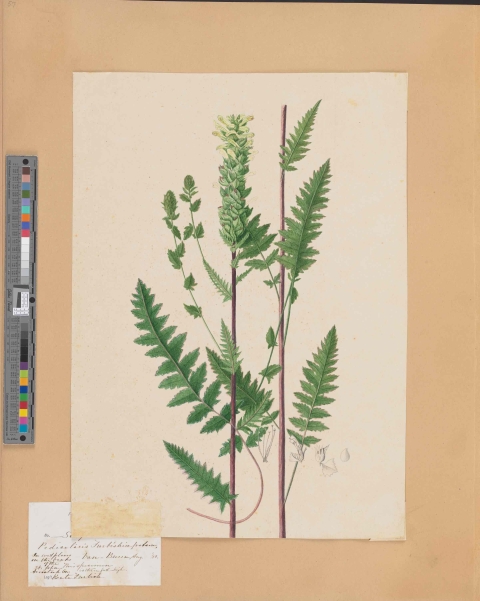

The plant has a special place in Maine’s history as well. Furbish’s lousewort was discovered by, and named for, a pioneering botanist and botanical artist from Brunswick, Maine, Kate Furbish, who was as tenacious as her namesake plant. The lousewort is known for persevering in stressful conditions; it depends upon periodic scouring of the river banks by ice in order to flourish.

Furbish too persevered; she explored parts of Maine that were considered desolate wilderness in the late 1800s despite how risky it may have been for a woman to do so at the time.

Two years after Furbish discovered the lousewort in 1880, James Dergavel Irving established a sawmill, gristmill, carding mill, general store, lumber business, and farm in New Brunswick that would grow into J.D. Irving, Limited.

J.D. Irving’s descendants embraced a business-savvy conservation mindset. In the 1950s, great grandson James K. Irving pioneered tree-improvement and reforestation programs that helped diversify its resources. Furbish’s lousewort was not known to be part of the portfolio: at the time, as it was thought to be extinct.

Several decades later, in the 1970s, the lousewort was rediscovered and soon listed as federally endangered. Not long after its rediscovery, it was also found growing on Irving’s land.

State partnership

Over the years, the state of Maine has played a key role in shepherding the plant’s recovery. Supported by funding from federal endangered species grants, Maine identifies, monitors, and protects habitat for Furbish’s lousewort in partnership with the Service, private landowners, and forest-products companies like Irving.

With Irving’s permission, the Maine Natural Areas Program surveys along the Saint John River annually, and provides Irving and other landowners with updates on the status of the species.

“Working cooperatively with the Irving Company has been critical to advancing our knowledge of the species,” says Don Cameron, a botanist for the Maine Natural Areas Program, who has been involved in monitoring Furbish’s lousewort for two decades.

That information is integrated into Irving’s own Unique Areas Program, which was started in the early 1980s as a way to catalog and protect all of the natural assets found in its woodlands.

Growing collaboration on private lands

Irving is one example of a growing collaborative effort between private forest owners and the Service to conserve species on private lands. Wildlife conservation is an integral part of forest management plans across the country, and conservation projects that prioritize collaboration among key interests is proving to drive conservation success stories like Furbish’s lousewort.

Groups like the National Alliance of Forest Owners (NAFO), of which Irving is a member, bring together private forest owners and other interested parties with the shared goal of realizing conservation benefits at scale. Through its Wildlife Conservation Initiative, NAFO brings millions of acres of privately-owned forests into conservation projects with the Service, state departments of natural resources, and other key stakeholders. Today, NAFO’s Wildlife Conservation Initiative counts a dozen projects across the country.

“We realize there are many rare, threatened, and endangered plants within our operable forest, and as a forest management company, we consider ourselves a steward of this land,” said John Gilbert, Irving’s manager of fish, wildlife, and development. “A healthy, functioning landscape provides greater benefits to the public, and produces better forestry products.”

It’s thanks to these collaborative efforts to maintain a healthy, functioning landscape for Furbish’s lousewort throughout its range that the Service is downlisting the species.

Boots on the ground

For its part, Irving has protected nine large sites, encompassing 457 acres, along the Upper Saint John for Furbish’s lousewort, out of a total of 1,561 sites it has set aside to preserve rare plants and animals on its lands. These unique areas range in size from 1.2 acres to thousands of acres, depending on the habitat type or the needs of the rare species.

But the unique areas program isn’t confined to these parcels. Irving’s foresters are constantly on the lookout for species of interest. In fact, they are trained to be.

“Every year, we get our planning foresters — the people who are out there day to day, boots on the ground — to a point where they can recognize certain habitat types associated with rare plants in Maine,” Honeyman said. He explained that they focus on characteristic habitat types because there are more than 400 rare plants in the state, an ambitious number for anyone but a professional botanist to learn to identify.

“Our training program is designed to get staff to recognize eight specific habitats, and if they find them, to ask us to take a second look,” he said. “This approach has been very successful in finding a number of rare plants in Maine’s North Woods, whether they are rare because there are few of them, or because there just aren’t a lot of people looking for them.”

In addition to Furbish’s lousewort, Irving’s lands (including in Canada) are home to downy rattlesnake plantain, fir clubmoss, Jacob’s ladder, and common moonwort, not to mention a myriad of rare birds, mammals, fish, reptiles, amphibians, and insects.

“All of our staff look forward to that training, and are very interested in what we find,” said Honeyman. “It makes sense if you think about it: People who work in forestry love the outdoors.”

That suggests Irving’s foresters might agree with Kate Furbish, who after her discovery in northern Maine remarked in a speech to the Portland Society of Natural History: “Had I listened to those who discouraged me from going into that part of the state because the Flora would not be likely to repay me for the expense and fatigue, I should be as ignorant as they are of its natural beauties.”

Irving, too, recognizes the Great North Woods are worth a closer look.