A Furbish’s lousewort by any other name would not be a milestone in women’s history. And the woman for whom the plant was named was well aware of that fact.

We know because on April 8, 1881, Kate Furbish wrote a letter pointing that out to Sereno Watson, the curator of Harvard University’s herbarium.

Quick backstory: Harvard’s herbarium was established by, and later named for, Asa Gray, who was something of a botanical celebrity in his day. Gray synthesized all existing knowledge about the plants of North America in his Manual of the Botany of the Northern United States, known colloquially as “Gray’s Manual.” No relation to “Gray’s Anatomy.”

As the curator of the herbarium, Watson was responsible for processing, describing and naming new specimens that were submitted to the collection, including a never-before-seen lousewort sent in by a botanist from rural Maine.

Which brings us back to Furbish’s letter, written as a follow-up to Watson’s positive reception of her submission. After accepting Watson’s invitation to visit him in Cambridge (they eventually became friends) Furbish called him out:

“My second reason for writing is to say, that were it not for the fact that I can find no plants named for a female botanist in your manual, I should object to ‘Pedicularis Furbishae’ for it is too often conferred to be any particular honor,” she wrote. “It” being the naming of a plant for its discoverer.

Furbish continued, “But as a new species is rarely found in New England and few plants are named for women, it pleases me.”

So Pedicularis Furbishiae it was, and since then, this rare plant has made a name for itself.

One of a kind

Furbish’s lousewort became one of the first plants to be added to the endangered species list in 1978, and has been mythologized for its role in helping to stop the controversial Dickey-Lincoln hydroelectric dam project, which would have flooded 80 thousand acres of Maine’s north woods, including most of this plant’s native habitat. The only place in the world where Furbish’s lousewort occurs is along the Saint John River in Maine and Canada; it depends upon periodic scouring of the banks by ice to provide the right conditions for it to grow, and to keep competitive plant species at bay.

Now the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is reviewing the status of Furbish’s lousewort, which has managed to persist despite threats to its habitat from erosion and development thanks to collaborative efforts by the Maine Natural Areas Program, Environment and Climate Change Canada, the forest products industry, and private landowners who have taken voluntary measures to protect the plant on their properties.

But the botanical contributions of the woman who discovered the plant have largely been forgotten.

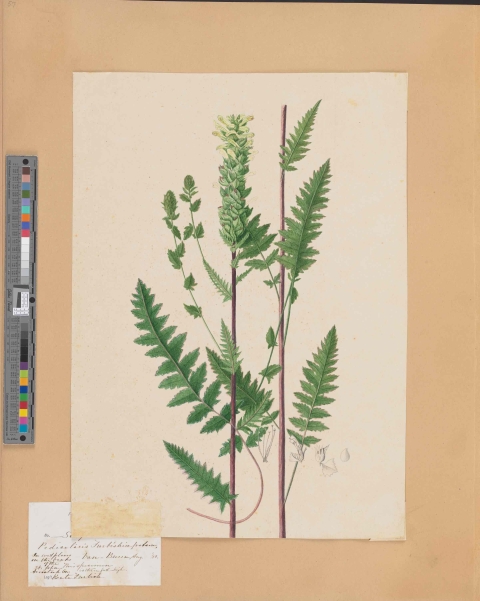

“History has painted Furbish as a gifted artist, and an ‘amateur’ botanist,” said Kat Stefko, who oversees Bowdoin College’s special collections. Among them, the Kate Furbish Collection, which includes journals, correspondence, research materials, and sixteen bound volumes of Furbish’s masterful sketches and watercolors of flowering plants.

But Stefko added, “The more you dig into this collection, the more you realize the sustained and significant contributions she made at a critical time in the history of field botany.”

All the more remarkable considering the barriers that would have kept Furbish from pursuing a career in this field along the most direct route, say through a degree in science at Harvard or Yale. She found her own way.

Budding ambition

Furbish developed a knowledge of plants at an early age thanks to her innate curiosity about the natural world and some practical training from her father, who cultivated vegetables to sell at his hardware store in Brunswick, Maine.

As a young adult, she studied art, first in Portland, then in Boston, then in Paris, using a brush to learn the fine morphological details key to field identification. “Many people would say it was the other way around, but I think she turned to art to support botany,” Stefko said.

By 1870, when she was in her mid-thirties, Furbish had set her career goal. “She determined she was going to identify all of the flowering plants in Maine and do watercolor renderings of them as aids for identification.”

I told Stefko that sounded ambitious.

“It was very ambitious,” she confirmed. “We know that she had an herbarium at her house that at some point numbered more than 4,000 sheets.” That is, pieces of paper displaying pressed, dried plant specimens. To ensure that her watercolors would be reliable aids to identification, Furbish needed to have multiple specimens capturing every plant at every life stage.

But she wasn’t just using these sheets to inform her paintings, she was sending them to academic institutions, including Bowdoin, to inform their research. Stefko said these herbarium sheets were considered extremely valuable. “It’s serious business what she’s doing.”

That’s because identifying plants was serious business. As in, life and death. At the time, most medicines were derived from plants, and training in homeopathy was a fundamental part of the curriculum at medical schools, including Bowdoin’s (which closed in 1921).

Unstoppable

Furbish was instrumental in helping to build a network of botanical knowledge in the 19th century that connected her to scholars like Asa Gray, and scholarly institutions like Harvard, where she would not have been admitted as a student.

She helped research herbariums grow by doggedly pursuing, collecting, and identifying rare species in parts of her state where few dared venture.

Aroostook County, where Furbish found the lousewort, is still considered far afield. “The county,” as it’s known, encompasses nearly a quarter of Maine’s area, and about five percent of its population. In the late 1800s, Aroostook might as well have been the Arctic. Exploring this wilderness would have been unthinkable for most, and especially for a single woman.

Fortunately, Furbish had a mind of her own.

“Had I listened to those who discouraged me from going into that part of the state because the Flora would not be likely to repay me for the expense and fatigue, I should be as ignorant as they are of its natural beauties,” she said in a speech for the Portland Society of Natural History in 1883, blithely titled, “An Evening in the Maine Woods.”

To be sure, she faced challenges: riding on a mail coach “with no back to the seat, and no springs to the carriage,” narrowly avoiding falling into a ravine at the expense of her tools (“I exclaimed in my despair, Alas! For they were borrowed!”)and braving “interminable bogs” where men had ventured never to be seen again. “But I found no skeletons, had no misgivings, and always enjoyed surmounting every obstacle which presented itself,” she said.

Stefko put it differently: “She was unstoppable.” And her resulting achievements, remarkable.

“There are other important herbarium collections, but to have an important herbarium collection and these watercolors?” Stefko marveled — there are 1,326 of them. “It is a massive, singular collection. There is nothing like it.”

It’s fitting then that Furbish was the one to discover the lousewort; it too is singular. Not only is the plant found only along the Saint John, “No one really knows how it got there,” said Mark McCollough, an endangered species specialist for the Service. Its closest known relative grows in the Rocky Mountains.

“Somehow, this plant found a little foothold along the Saint John, where it has persisted since the last glaciers receded,” McCollough said.

Neither Furbish nor her lousewort were deterred by the fact that they didn’t belong.

The effort to conserve at-risk wildlife and recover listed species like Furbish’s lousewort is led by the Service and state wildlife agencies in partnership with other government agencies, private landowners, conservation groups, tribes, businesses, utilities and others. It has drawn support for its use of incentives and flexibilities within the ESA to protect rare wildlife, reduce regulations and keep working lands working.