In the Atlantic Ocean the Atlantic salmon is known as the “King of Fish.” They were once found in most coastal rivers northeast of the Hudson in New York. Unfortunately, overfishing and dams that blocked their ability to reach their preferred spawning grounds, reduced their numbers until populations were greatly diminished. Currently, the last wild populations of U.S. Atlantic salmon are found in a handful of rivers in Maine, but our National Fish Passage program and the Craig Brook and Green Lake National Fish Hatcheries are working with partners to ensure these fish continue to make their journey up stream.

Life Cycle of Atlantic Salmon

In late autumn, female Atlantic salmon dig a shallow nest (called a redd) in a gravelly riverbed. They bury their fertilized eggs under a foot of gravel in the redds and leave them over the winter. The eggs hatch in April and May. After three to four weeks, the baby salmon swim up through the gravel to hunt for food. Young salmon spend one to three years in or very near the stream where they were born. When they are about 6 inches long and ready to live in saltwater, they become silver in color and migrate to the ocean - swimming and surfing the ocean currents to their feeding grounds near Greenland.

Migration of Maine's Atlantic Salmon

Atlantic salmon make an epic migration in their lives, swimming thousands of miles across the North Atlantic. Typically, adults will spend two winters at sea before migrating back to their natal rivers to spawn. Unlike Pacific salmon, which always die after spawning, Atlantic salmon often survive spawning and may migrate back out to sea with the chance of returning to spawn again. Female repeat spawners are an important dynamic to the species survival since these older fish are more fertile and produce larger eggs with a better chance of survival. The tragic tale of Atlantic salmon in the United States. Atlantic salmon in the U.S. were once found in almost every coastal river northeast of the Hudson River in New York. In Maine, runs up the Penobscot once numbered in the hundreds of thousands in the 1800s prior to industrialization taking its toll on the population. By 1865, the salmon populations of the Northeast had greatly declined due to dams, pollution, and over-harvest. These contributed to the Maine commercial fisheries closing in 1948, with recreational following in 2000. Annual returns in recent years have been in the hundreds. The Maine Fisheries Commission's first report over 150 years ago, in January of 1868 stated: "The salmon is suffering from neglect and persecution. So peculiarly is it exposed to the attacks of man, so greedy and relentless has been the pursuit, and so regardless of their necessities has been the management of the waters, that in many rivers, both in Europe and America, it has become utterly extinct, and in very few of the remainder does it yield anything like the number that is was wont." Protection and hope for the future of Atlantic salmon. Wild and hatchery-reared Atlantic salmon in eight Gulf of Maine coastal rivers were listed as endangered under the protection of the Endangered Species Act in December 2000. In July 2009 protections expanded to include the Penobscot, Kennebec, and Androscoggin rivers, along with a designation of critical habitat found in Maine. In 2019, the Recovery Plan for the Gulf of Maine Distinct Population Segment of Atlantic Salmon was completed with the goal of a sustainable wild population in 75 years.

National fish hatcheries work to conserve wild Atlantic Salmon.

Today three national fish hatcheries raise Atlantic salmon to support their recovery in the wild.

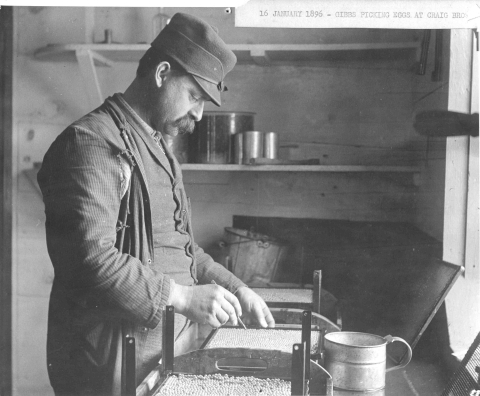

Craig Brook National Fish Hatchery was established officially as a federal hatchery in 1889 but it had already been operating since 1871, under the direction of fish culture visionary Charles Atkins, through an agreement among several states of the Northeast. Atkins had searched throughout Maine for the perfect location to raise Atlantic salmon to restore the declining species. The site Atkins selected was a vacant mill located at the mouth of Craig Brook on Alamoosook Lake in mid-coast Maine. This began a 48-year career that would earn him a legacy as a pioneer in fisheries conservation and the title "The Father of Atlantic Salmon culture". Over 3 million eggs are produced annually at Craig Brook National Fish Hatchery to support recovery actions, produce future broodstocks, and perpetuate the living gene bank.

Green Lake National Fish Hatchery is a large-scale cold-water hatchery located in Downeast Maine. Built in 1973, the mission of the hatchery has changed from supplementing Atlantic salmon populations in the Penobscot, Merrimack and Connecticut rivers , to a conservation hatchery dedicated to raising river-specific strains of endangered Atlantic salmon for Gulf of Maine rivers. Three out of every four Atlantic salmon returning to U.S. waters come from Green Lake National Fish Hatchery.

Nashua National Fish Hatchery was established in 1898 and is one of the oldest national fish hatcheries still operating today. Programs at the hatchery support Atlantic salmon, Landlocked Atlantic salmon, American shad, and other aquatic species restoration efforts in many New England waterbodies. Hatcheries serve as a living gene bank for future recovery. The brood populations originate from rivers like the Penobscot, Machias, Narraguagus, Sheepscot, East Machias, Dennys, and Pleasant rivers. These populations are kept genetically distinct as a safety net to prevent extinction and provide genetic resource needed to produce the next generation of Atlantic salmon.

The mission of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service is working with others to conserve, protect, and enhance fish, wildlife, plants, and their habitats for the continuing benefit of the American people. Whether you are an angler, a nature enthusiast, or have heritage ties that connect deeply with this species, this recovery effort is made so that Atlantic salmon and the benefits they provide to the environment will be available for future generations. Bottom line: We do all of this for you!