This lanky, medium-sized, mottled brown shorebird with a decurved bill once darkened the skies with its migrations across the North American continent. In the 1850s, observers described flocks of calling birds that stretched for miles every spring and fall, their voices sounding like the distant jingling of sleigh bells.

The curlews fattened up on tundra berries in their Arctic breeding grounds in summer, then flew almost nonstop along the eastern fringe of North America to the South American pampas each winter. Upon their return north each spring, they gorged on the larvae and eggs of great hordes of Rocky Mountain locusts (a now-extinct grasshopper) in the Great Plains and prairie.

But the Eskimo curlew’s life history is increasingly just that: history. Few New World species have suffered such rapid decline. Eskimo curlews, once exceedingly common — numbering in the hundreds of thousands, possibly millions — became rare toward the end of the nineteenth century. None have been seen since 1963, when two migrating individuals were spotted on Galveston Island, Texas, and another was killed by a hunter in Barbados in September of the same year.

During the days of “market hunting”—an unfettered and often profligate practice of killing wild birds for consumption that flourished in the late 1800s—the Eskimo curlew was highly sought after. One of its nicknames among hunters was “doughbird”, alluding to the ample fat reserves on migrating birds. For decades, these birds were hunted 11 months out of the year. It was known as a thoroughly unsuspecting target: Eskimo curlews would circle back to wounded members of the flock, calling out repeatedly until they too were felled by the guns. Even after market hunting was officially banned in 1909, and after passage of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act in 1918, the Eskimo curlew didn’t rebound. It was on the brink of extinction.

But hunting alone can’t explain the demise of the Eskimo curlew. In the decades leading up to its disappearance, the lush grasslands that provided stopover habitat for curlews migrating across the continent were largely converted to agricultural fields.

Settlers suppressed the wildfires which formerly burned the Great Plains with regularity. This removed the large-scale habitat disturbance that favored curlews and their feeding habits. At the same time, a primary food source for the curlew — the eggs and larvae of that Rocky Mountain locust, which once swarmed billions of insects strong and spanned miles in flight — was going extinct as the Great Plains and prairie were being plowed under.

In 1966 the Eskimo curlew was among the first species listed as endangered under the Endangered Species Preservation Act, the predecessor to today’s Endangered Species Act. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service completed the most recent five-year status review for this bird in 2021 with no new information on or change the species status, which was kept as endangered. Search parties organized at either end of the Americas have failed to turn any up.

The plight of the Eskimo curlew should humble us. Like the passenger pigeon, it was once so abundant that people simply couldn’t imagine it gone — or that human activity could have any appreciable impact on their numbers. But the passenger pigeon went from nearly 5 billion individuals in the early 1800s to a sole survivor, Martha, who died in 1914 in the Cincinnati Zoo.

Today, most bird species worldwide are in decline. Since 1970, more than three billion birds have disappeared from North America alone. While recent declines might not be as swift and dramatic as those of the passenger pigeon and Eskimo curlew, they are no less troubling. Birds are bellwethers of ecosystem health: their absence can point us toward larger systemic issues. When we lose birds, we lose so much more.

Troubled curlews

Curlews are iconic birds of wild, wet, evocative places—estuaries, mountain slopes, prairies and coast. But these shorebirds are threatened by habitat loss, climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change , and human disturbance.

Around the world, there are eight species of curlew. Of those, two haven’t been seen in decades: the Eskimo curlew (Numenius borealis) and slender-billed curlew (Numenius tenuirostris). Last seen in 1995, the slender-billed curlew has been decimated by habitat loss and excessive hunting on its Mediterranean wintering grounds. On the other end of the spectrum, two species have populations that are still relatively stable: the Little curlew (Numenius minutus),a small Old World curlew of the grasslands in Eurasia and Australia, and Whimbrel (Numenius phaeopus), the most widespread curlew species whose range spans both the New and Old Worlds. The others fall in-between:

In North America, the New World Long-billed curlew (Numeniusamericanus) still breeds in grasslands and high desert and winters on estuary shores but its numbers are declining across much of its range.

The Far-Eastern curlew(Numenius madagascariensis) is the world’s largest curlew and largest extant sandpiper. It’s listed as endangered by the IUCN Red List with fewer than 40,000 individuals remaining. This Old World curlew spends its breeding season in northeastern Asia and most overwinter in coastal Australia.

Breeding in the mountains of Alaska and wintering in the South Pacific, the Bristle-thighed curlew(Numenius tahitiensis) is currently classed as vulnerable by the IUCN Red List. Population declines are due to predation on molting (flightless) adults by introduced predators on their wintering grounds.

Found worldwide, the Eurasian curlew(Numenius arquata) is listed as vulnerable by the IUCN Red List. This Old World Species breeds from Britain to Central Asia and is decliningdue to loss of grassland habitat.

Call to Action

How do you find a bird that hasn’t been documented in almost 60 years? You could crowd-source your search effort, asking anyone for tips or photos of the bird in question — a 21st century twist on the “Have You Seen Me?” ads on milk cartons: “Missing, last seen in 1963. Considered a flight risk; highly migratory.”

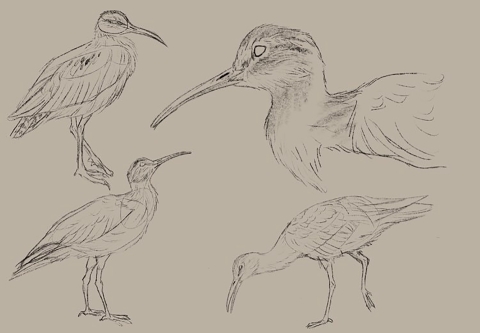

But Eskimo curlews are commonly confused with other curlews. While diminutive in stature and bill size compared to the other curlews, Eskimo curlews most closely resemble juvenile whimbrels. Whimbrels take time to grow their bill long enough to differentiate it from an Eskimo curlew (adult whimbrels are slightly larger with a longer, more curving bill and white wing linings).

In your search for that elusive curlew, take photos and study the birds closely. At the very least, you will enjoy your time outdoors and come to appreciate this genus of wading migratory shorebirds with their down-curved bills and mottled plumage. There are plenty of shorebird festivals where you can see curlews, such as the bristle-thighed curlew and whimbrel at the Kachemak Bay Shorebird Festival. April 21 is designated as World Curlew day, a grass-roots initiative to raise awareness of the plight of curlews and to encourage activities to help them.

Perhaps you will feel inspired to act on the behalf of all curlews. All birds. To ponder loss but maintain hope.

Story by Peter Pearsall (former Communications Specialist for External Affairs/Migratory Birds) and Katrina Liebich

In Alaska we are shared stewards of world renowned natural resources and our nation’s last true wild places. Our hope is that each generation has the opportunity to live with, live from, discover and enjoy the wildness of this awe-inspiring land and the people who love and depend on it.

Follow us: Instagram Facebook X Apple Podcasts