The Extinction Crisis

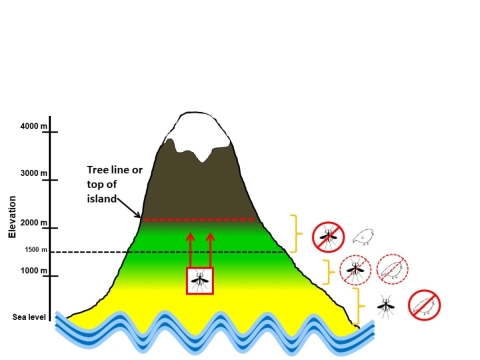

Hawai‘i's endemic forest birds are facing an immediate extinction crisis. Avian malaria, a disease transmitted by invasive mosquitoes, is driving the extinction of Hawai‘i's forest birds and for some species a single bite from an infected mosquito can be deadly. Once, there were more than 50 species of honeycreepers spread throughout the islands; however, today only 17 species remain, most of which are restricted to small area habitats too cold for mosquitoes to thrive. A few species, like the kiwikiu (Maui parrotbill) and ‘akikiki (Kauaʻi honeycreeper), have less than 200 individuals remaining in the wild and could go extinct in as little as two years. As climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change accelerates, mosquitoes are expanding their range into upper elevation forests, threatening what little safe habitat these birds have left.

The immediate need for many of the forest birds to persist in the wild is landscape-scale control of the invasive mosquitoes. Agencies from the U.S. Department of Interior and the State of Hawai‘i are working with partners in the "Birds, Not Mosquitoes" Working Group to develop and implement a plan for controlling invasive mosquitoes using a naturally occurring bacteria, Wolbachia, that prevents mosquitoes from reproducing. While work continues developing the resources needed to implement mosquito management in forest bird habitat, effective implementation will likely come too late for the species at highest risk of extinction. The Service is working with the State of Hawai‘i and other partners to use conservation tools like captive care and translocation to prevent those species from going extinct in the next two to five years, while simultaneously pursuing the longer term option for mosquito control.

In Hawai‘i, natural resources are cultural resources as well, and when they disappear, so do their important roles in our heritage and communities. Now more than ever, it is important to work with the Native Hawaiian community and our partners to protect Hawai‘i’s forest birds for future generations.

A new report by the Service, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), and U.S. Office of Native Hawaiian Relations (ONHR) finds that some species have so few birds left they may go extinct in the next two years. Click Here to learn more.

Immediate Risk of Extinction for Four Hawaiian Forest Birds

The report, Hawaiian Forest Bird Conservation Strategies for Minimizing the Risk of Extinction: Biological and Biocultural Considerations, from the Service, USGS, and ONHR and published by the University of Hawai‘i Hilo, identifies four Hawaiian forest birds at risk of imminent extinction - ‘akeke‘e (Hawaiian honeycreeper), ‘ākohekohe (crested honeycreeper), ʻakikiki and kiwikiu – and the evaluates potential actions that could prevent their disappearance from Earth.

Avian malaria, a disease transmitted by invasive, non-native mosquitoes, is driving the forest birds’ extinction. Just one bite from an infected mosquito can kill a forest bird.

Biologists studying forest birds unanimously agree that all four species will likely go extinct in the next one to 10 years if something is not done to prevent the spread of avian malaria.

Conservation agencies, non-profits, community groups and others are working together to find a way to prevent the spread of avian malaria. However, these efforts are several years from being able to be implemented and just one year of increased temperatures caused by climate change could lead to the earlier extinction of the four bird species most at risk.

This summary report gathered the most up-to-date scientific information about the four bird species, including the knowledge and perspective shared by members of the Native Hawaiian community.

- You can read the entire report by Clicking Here.

- You can read the Hawaiʻi Department of Land and Natural Resources and U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service news release by Clicking Here.

- You can read the about the multiagency strategy to preventing the imminent extinction of Hawaiʻi forest birds by Clicking Here.

Learn more about:

Frequently Asked Questions

Q: How are Native Hawaiian perspectives being considered by conservation managers?

A: The recent report produced by U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and U.S. Office of Native Hawaiian Relations provided the most up-to-date scientific and biocultural information available. From the report: “A majority of Native Hawaiian participants viewed management decisions around ‘akikiki, ‘akeke‘e, kiwikiu, and ‘ākohekohe akin to making end of life choices for members of their ‘ohana. While most participants thought immediate steps should be taken to prevent the extinction of these species, extinction was not always considered the worst-case scenario. Instead, the likelihood of success; welfare of individual birds; and social, biocultural, and cultural connection of the birds to their natural environment were significant considerations when evaluating management options. If these considerations could not be fully realized, some participants considered it more appropriate to allow the birds to go extinct in their natural environment without further intervention, akin to allowing a member of their ‘ohana to breathe their last breath in their “one hānau,” or birthplace.” (Eben, et. al. 2022)

Conservation managers are using the information provided from both biological and biocultural experts as the determine next steps for each of the four species at risk of imminent extinction. In addition, some of the next steps may require regulatory and public engagement processes that will allow additional time for conversation and listening to the community and the public’s perspectives.

Q: What are the Service and the State of Hawai‘i going to do to prevent the immediate extinction of the four forest birds?

A: The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and State of Hawai‘i will work with partners to determine the conservation actions that will benefit the birds the most and ensure their individual welfare. Some birds will require temporary captive care until the threat from invasive, non-native mosquitoes and avian malaria can be reduced. Other birds are more difficult to capture and hold in captivity, and so may be left in the forest habitat until the mosquito threat can be addressed or a conservation translocation may be considered.

Q: When can we expect landscape-level control of avian malaria? What conservation tools will you use until then?

A: Biologists and conservationists across Hawai‘i are working to find ways to save forest birds: from dealing with predation by introduced species to landscape scale control of mosquitoes. The only long-term solution for many of the forest birds to persist in the wild is landscape-scale control of the invasive mosquitoes. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and State of Hawai‘i are working with partners in the "Birds, Not Mosquitoes" Working Group to develop and implement a plan for controlling invasive mosquitoes using a naturally occurring bacteria, Wolbachia, that prevents mosquitoes from reproducing. Work continues on developing the resources needed to implement mosquito management in forest bird habitat and environmental compliance and public engagement will need to take place before any management actions occur. Keeping that in mind, some small scale, local projects may take place in the next few years. Until then, conservation managers will have to use existing tools, such as bringing species into temporary captive care and potentially translocating some species to prevent their extinction.

Q: When bringing birds into captive care, will you move them to the mainland?

A: The preference of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the State of Hawai‘i is to keep threatened and endangered birds in the wild. However, when it is necessary to prevent their extinction, we will consider captive care as a temporary option until the birds can be restored to their native habitat. The agencies are committed to placing birds that require captive care in Hawaiian facilities first, however captive care facilities currently available in Hawai‘i are already close to full. Additional captive care facilities and space are needed and both agencies are seeking the capacity, resources, and partnerships to build the facilities and expertise we need locally. Captive care is an interim solution to the extinction crisis, meant only to prevent these species from disappearing from Earth.

Currently, there are 41 ‘akikiki, seven ‘akeke‘e, and two kiwikiu in captive care at the Maui Bird Conservation Center and Keauhou Bird Conservation Center on the Island of Hawai‘i. These facilities are managed by the San Diego Zoo Wildlife Alliance through the Forest Bird Conservation Breeding Partnership between SDZWA, USFWS, and Hawai‘i Department of Land and Natural Resources, Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Q: What is captive care?

A: Captive care involves the removal of forest birds from the wild and placing them in a managed conservation facility under human care. Captive care includes both long-term conservation breeding and short-term, temporary care. The long-term conservation breeding programs are used to prevent extinction and supplement wild populations and the short-term holding of birds takes place only until they can be released back into the wild once their habitat is safe for them to return or a new, safer forest. Captive care is a strategy that is currently being used to help prevent the extinction of the ‘akikiki, ‘akeke‘e, and kiwikiu.

Q: What is conservation translocation?

A: Conservation translocation is the deliberate movement of species from one location for release in another for the purpose of their conservation or recovery. For forest birds, conservation translocation could occur by moving individual birds from their current range to a suitable, disease-free site on another island or translocation from captivity, which entails removing individuals from their current range and maintaining them in a controlled facility under human care for a short period while waiting for translocation planning to be completed.

Conservation translocation has been used successfully throughout the Pacific Islands, however, forest birds face additional challenges posed by the expanding invasive, non-native mosquito population. Conservation agencies attempted to create a second population of kiwikiu on the south slope of Haleakalā in 2019 by translocating individuals from the north slope and from captive care. Unfortunately, warmer temperatures caused by the changing climate allowed mosquitoes to move into the habitat that was previously thought to be safe. Most of the birds died from avian malaria. Until we have a way to suppress mosquito populations and prevent the spread of avian malaria, forest birds will continue to be threatened throughout Hawai‘i.