Longleaf pine trees once blanketed the landscape from southern Virginia to east Texas.

Longleaf pines were majestic hallmarks of the Southeast. They are perfectly suited for the region. They are drought-resistant, fire-resistant, disease-resistant, insect-resistant, even hurricane-resistant. The longleaf pine ecosystem is vital to many other native plants and animals, including the gopher tortoise and the Eastern indigo snake.

Now, after centuries of harvesting, just five to six percent of the longleaf ecosystem remains.

Lots of Southerners – including four passionate Georgians we are about to meet – are working hard to save existing stands of longleaf pine and plant new ones. They are working with state agencies, nonprofit organizations, corporations and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Partners for Fish and Wildlife Program.

The Partners Program, as it is known informally, works with private landowners, nonprofit organizations and government agencies to restore, enhance and conserve land. Since 1987, the program has worked with 45,000 private landowners and 5,000 organizations nationwide to restore 4 million upland acres, 1.5 million wetland acres and 12,000 miles of streams for the benefit of fish, wildlife and people.

One goal of such voluntary cooperation is to conserve enough habitat to keep at-risk animals and plants off the endangered species list. Biologists consider a species “at risk” if it faces grave threats to survival. In the Southeast alone, working with private landowners and other conservation partners has precluded 98 species in 10 states, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands from being listed.

Here are four ardent Georgians working with the Partners Program and others to conserve longleaf pine:

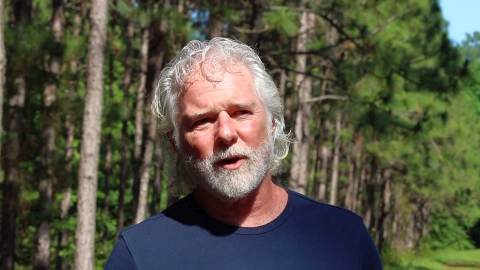

Reese Thompson / Wheeler County

The man and his land

Reese Thompson is a sixth-generation Georgian who has been producing timber for 44 years. Through forestry, his family has been tied to private land southwest of Vidalia for more than a century. “The longleaf pine tree is the premier pine species,” he says. “I was fortunate to have been entrusted with some natural longleaf.”

His conservation practices

Thompson believes it is especially important to preserve existing longleaf pine by managing it carefully. That includes thinning it occasionally and setting prescribed (controlled) fires periodically to stimulate the native ground cover, or understory.

He conserves what he calls the three-legged stool of longleaf – the timber; the intact ground cover; and sensitive species, such as the gopher tortoise and the Eastern indigo snake. “The gopher tortoise is referred to as the keystone species because he provides a burrow that’s used by some 300 other species of animals,” Thompson says. He adds that “the jewel, the real treasure,” is the native understory because it includes 800 to 900 plant species.

Thompson is replacing faster-growing slash pine he has cultivated for decades with new longleaf. Partners Program funding has helped him buy longleaf seedlings. And he has even trademarked a Smokey Bear-like character named Burner Bob, a bobwhite quail designed to spread the message that fire is good for longleaf pine ecosystems and associated wildlife.

His philosophy

“Conservation is my passion. It’s my mistress. It’s my hobby. It’s my profession. It’s my life’s mission to protect, enhance and restore the longleaf that I’ve been entrusted and to set a good example for the next generation."

Chuck Leavell / Twiggs County

The man and his land

Chuck Leavell is a world-class pianist who has played with the Rolling Stones, the Allman Brothers and others. He is deeply involved with forest conservation nationally and is author of several books, including Forever Green: The History and Hope of the American Forest. He and his wife, Rose Lane, grow timber for harvest and production on Charlane Plantation, land south of Macon they inherited from her grandmother. “This is a family heritage of stewardship of the land. We want to pass the land on to our daughters, and to our grandchildren.”

His conservation practices

Recognizing that two faster-growing pine species – loblolly and slash – have displaced slower-growing longleaf over time, Leavell values longleaf. He grows longleaf to harvest straw, which is prized as landscaping material. He stresses the importance of prescribed fire to longleaf, saying that fire “allows natural grasses and legumes to come up and helps to reduce competition within the stand.” There is abundant wildlife on his land – quail, deer, wild turkey, black bear. So far there is no evidence of gopher tortoise or Eastern indigo snake. But, he says, “I think the effort to keep them in the Southern landscape is a great thing.” The Partners Program has helped him plant longleaf.

His philosophy

“When I dream about what the Southeast, this territory here in Georgia, would have looked like before European settlement, and I think of all those incredible longleaf pines in the landscape at that time, you know, it just conjures up such a great vision for me, and that’s why I want to engage in the restoration of longleaf – because I just have this picture in my mind of what it would have looked like back then.”

John Littles / Long County

The man and his land

John Littles, a native Georgian, is executive director of nonprofit McIntosh SEED. The organization’s mission is “to create and sustain healthy and diverse rural communities through community and economic development, community organizing, conservation, and direct services across the Southeast.” McIntosh is a coastal county, and SEED stands for Sustainable Environment and Economic Development. In 2015, with help from the Conservation Fund, McIntosh SEED purchased 1,148 acres of land in neighboring Long County as a community forest.

His conservation practices

Littles and his organization are establishing the community forest as a place of education and recreation for underserved poor people. A private forester is overseeing McIntosh SEED’s management of the forest under a conservation easement conservation easement

A conservation easement is a voluntary legal agreement between a landowner and a government agency or qualified conservation organization that restricts the type and amount of development that may take place on a property in the future. Conservation easements aim to protect habitat for birds, fish and other wildlife by limiting residential, industrial or commercial development. Contracts may prohibit alteration of the natural topography, conversion of native grassland to cropland, drainage of wetland and establishment of game farms. Easement land remains in private ownership.

Learn more about conservation easement . In addition to thinning trees, doing prescribed burning, holding workshops to educate community members, and beginning to develop walking trails, Littles and McIntosh SEED are reintroducing longleaf onto the land. The Partners Program has provided funding over the past two years to help plant longleaf pine seedlings. “Without that resource and that partnership, we would not be at this stage,” he says. Gopher tortoises have been documented in the community forest, but not Eastern indigo snake.

His philosophy

“For us at McIntosh SEED, our vision is to develop a model of these conservation practices so that African Americans and anyone in the entire community would have access to seeing some of these models and practices they can also engage in.”

Patricia McCarthy / Ware County

The woman and her land

Patricia McCarthy is a former science teacher and a timber woman who manages her family’s private farm near the Satilla River northwest of Waycross. She takes what might be called holistic approach to her working land. “Longleaf is a part [of her property]. It’s not the whole. But it’s a part. It was here in the beginning, and it needs to be here,” she says. Besides producing longleaf for straw, she grows pecans and blueberries.

Her conservation practices

“When you manage your longleaf well, then you’re able to leave part of your land in a natural state,” she says. “Nothing is more beautiful than a piece of land that you’ve left in a natural state.” Gopher tortoises and Eastern indigo snakes inhabit her property – “lots of them,” she says – plus deer, wild turkey and quail. “The wildlife and the longleaf and the creek bottoms – all of the land – go together. And it’s important to keep those together.” The Partners Program has provided funding for longleaf planting – and advice. “Robert Brooks has answered many questions,” she says, referring to the program’s Georgia coordinator. “He’s very helpful and very knowledgeable.”

Her philosophy

“The land becomes a member of the family. And just like if you had a member of the family that was older or could not speak for themselves, or couldn’t do for themselves, you would do for them. And that’s what you do for the land.”

At-Risk Species

The gopher tortoise and the Eastern indigo snake are listed as threatened species under the Endangered Species Act. Both depend on, and thrive in, longleaf pine habitat.

Gopher tortoises can live up to 80 years in the wild. They dig burrows for protection. The burrows, which provide shelter for about 360 other species, vary from three to 52 feet long and nine to 23 feet deep.

The non-venomous Eastern indigo snake, named for its glossy blue-black color, is the longest snake in North America. Males can reach 8.5 feet, females 6.5 feet. Land stewards such as Reese Thompson, Chuck Leavell, John Littles and Patricia McCarthy are vital to efforts to remove these at-risk species from the list. As a result of private landowners and conservation partners working with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service across the Southeast,13 listed fish, wildlife and plants have been upgraded from endangered status to threatened – or have been removed from the list altogether because they are recovered. These include wood stork, West Indian manatee and Louisiana black bear.

As the South Once Was

Longleaf pine trees can live to be 300 years old and grow to 100 feet tall. One reason longleaf needs help today is that its timber, which is strong and straight with few knots, was highly valued during the Industrial Revolution. It was used for ship masts, utility poles, even the base of the Brooklyn Bridge. The tree gets its name from its needle-like leaves, which can be 18 inches long and to this day are prized and profitable as landscaping straw.

This short video touches on what Reese Thompson, Chuck Leavell, John Littles and Patricia McCarthy are doing to conserve and restore longleaf pine.

More about longleaf pine and related conservation efforts

- U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Partners Program Facebook page

- The Longleaf Alliance

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service

- Georgia Forestry Commission