Weather atop North Carolina’s Black Mountains, the highest range in the Appalachians, can be notoriously fickle. But on a recent May afternoon, it was postcard perfect as Sue Cameron, a biologist with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, slowly made her way through a field of dense blackberry bushes rising above her head, bright orange marker flags in her hand. Every few feet she planted one of the flags in the ground, marking the spot where a young red spruce tree would be planted.

“We should bring face shields for whoever works in this field,” she said, channeling her frustration with the blackberry thicket to the well-being of those who will follow in a couple of weeks to plant trees where she planted flags.

Playing a long game, Cameron worked with staff from Southern Highlands Reserve, a non-profit arboretum and botanical garden, to gather red spruce cones from this mountain range. She helped secure funding so they could grow them into trees. She brought state park and other natural resource experts to the site and phoned and emailed those who couldn’t get their boots on the ground to solicit their input. She organized the effort to haul 327 young red spruce trees to the site, and she mustered 38 people out on a cool, overcast May morning to put those trees in the ground - the first planting in the effort to restore red spruce in the Black Mountains, helping convert this dense blackberry thicket back to the conifer forest it once was.

Red spruce and Fraser fir – a rough 20th century

North Carolina’s Black Mountains are home to Mount Mitchell – the highest peak east of the Mississippi, and the centerpiece of Mount Mitchell State Park, the oldest park in the North Carolina state park system. Mount Mitchell and the Black Mountains have long been a tourism focal point, and just on the state park side of the border with Pisgah National Forest once sat Camp Alice, rustic lodging for visitors to the Black Mountains who first arrived via train, then automobile. Today there are no remnants of Camp Alice, and the cut that once held the train tracks, then the road, has been gated and converted to the Commissary Trail, providing hikers with a wide, gently sloping trail and ample views.

As the Black Mountains rose in prominence as a tourism destination, they also became a source of timber and one of many areas in the Southern Appalachians to experience unsustainable, logging by companies looking to extract timber and move on to the next stand of trees. In many places, including the Black Mountains, this logging was followed by intense and rampant wildfire, fueled by logging slash. As these two forces – tourism and resource extraction – played out in the Black Mountains, it very much influenced policy-making conversations about how to achieve a sustainable balance in the public forests of North Carolina, while the intense logging and wildfire dramatically altered the landscape.

Momentum emerges for red spruce restoration

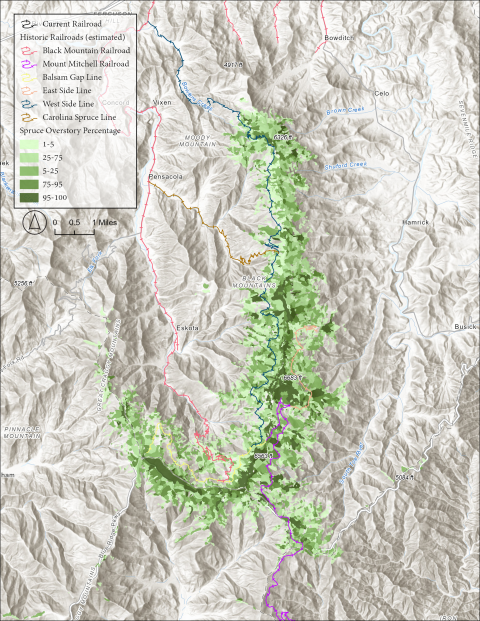

The highest peaks of Southern Appalachia are home to forests of red spruce and Fraser fir. Red spruce is common in eastern Canada and New England, but as you move south its distribution becomes patchy down the Appalachian spine, just reaching the highest peaks of southern Appalachia. Fraser fir is found only in the Southern Appalachians, and is a close relative to balsam fir, a common tree in New England and eastern Canada. This unique forest provides habitat for a host of rare species, including the endangered spruce-fir moss spider and Carolina northern flying squirrel.

The intense logging at the dawn of the twentieth century greatly reduced the expanse of these spruce-fir forests, and the subsequent forest fires altered the soil to a degree that the remnant trees could not easily recolonize denuded areas. Ensuing years also brought impacts from acid precipitation and the arrival of the balsam woolly adelgid, an invasive insect that kills Fraser fir trees. The result is that a century later we still have diminished spruce-fir forests.

Though the balsam woolly adelgid remains a threat to Fraser fir, air quality protections largely addressed acid precipitation in these high elevation forests, offering a glimpse of a brighter future. In 2012, rising interest among conservationists coalesced into the Southern Appalachian Spruce Restoration Initiative (SASRI), a partnership of state and federal agencies, non-profits, and private organizations, aimed at restoring red spruce.

As SASRI took shape, a team assembled around each of the high-elevation mountain ranges in Southern Appalachia, with Cameron taking lead on the Black Mountain team. Land ownership and management in the Black Mountains is concentrated into a small number of hands – North Carolina State Parks holds the highest portion of the range at their Mount Mitchell State Park, with much of the remaining land held by the U.S. Forest Service as part of the Appalachian District of Pisgah National Forest, and a private hunting and fishing club owning what is referred to as Big Tom Wilson Preserve, Tom Wilson being a local hunting guide whose family once owned a large portion of the area. Cutting across the southern end of the Black Mountains is the National Park Service’s Blue Ridge Parkway.

After studying spruce distribution maps and walking, driving, and utv’ing the land, Cameron landed on the area near the former Camp Alice as the potential site for the first spruce planting. It was easily accessible via the former road, now trail, and given the site’s current condition – a blackberry-covered field – there was little to lose and a lot to gain by planting spruce there.

“In November, 2021 I first hiked the site with Mount Mitchell State Park staff, getting an idea of what was possible,” said Cameron. “In July 2022 I returned, with State Parks, North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission, and other Service staff to dig deeper into exactly how and where the planting might be done and discuss any concerns people had. Obviously, North Carolina State Parks has been the lynchpin for this planting effort- without their tremendous support, we would be nowhere.”

Trees in the ground

Planting day, Wednesday, May 17, was set to be as turn-key as possible.

Twelve days earlier, Fish and Wildlife Service staff walked the site, flagging where each young tree would be planted and taking an on-the-ground look at logistics, like where the thirtyish expected planters could park.

The Monday before planting, Cameron and Asheville Field Office staff member Jeff Quast rendezvoused with staff from the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission to pick up the trees from Southern Highlands Reserve (SHR), in Lake Toxaway, North Carolina. SHR has become a leader in the propagation and rearing of red spruce, providing trees for not only this Black Mountain planting, but also plantings in the Great Balsams of Western North Carolina, Virginia Balsams of Southwest Virginia, and the Whigg Meadow area of East Tennessee. They’re currently fundraising for a new greenhouse to expand red spruce and other native plant production, an effort buoyed by attention brought by the selection of a local red spruce as the official Capitol Christmas tree.

Though pick-up trucks were the planned transport, the Wildlife Commission’s Ben Balke and Brandon Hyde were the heroes of the day, bringing with them an F-350 truck with a 16-foot utility trailer - large enough to carry nearly all 327 trees. With Hyde behind the wheel of the F-350, the small caravan drove the Blue Ridge Parkway to Mount Mitchell State Park, where the trees were unloaded and hauled down the Commissary Trail.

At 9:30 a.m. on planting day, the area around the Mount Mitchell State Park ranger station was the mustering site for a small army of tree planters:

- 21 volunteers from the North Carolina High Peaks Trail Association (whose presence was coordinated by former Service biologist and association member Russ Oates).

- Ben Balke from the N.C. Wildlife Resources Commission.

- Five faculty and students from Warren Wilson College.

- Six staff members from the Service’s Asheville Field Office.

- Five staff members from North Carolina State Parks.

Weather on planting day couldn’t have been better – cool and overcast, but no precipitation falling – perfect for hauling trees and swinging a shovel. The planting crew broke into small groups, loaded the trees into reusable grocery bags donated by Ingles Grocery, and fanned out across the slope to find the marker flags and put trees in the ground. With such a massive outpouring of support, the actual tree planting was perhaps the fastest part of the whole process, wrapping up just after noon.

“One of the fascinating parts of this effort is how much it relied on partnership,” said Cameron. “Southern Highlands Reserve raised the trees, the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission helped transport them to the site and plant them, planting day was a huge success with volunteers from Warren Wilson College and High Peaks Trail Association, and of course the blessing and assistance of North Carolina State Parks was fundamental. The whole day couldn’t have gone smoother.”

The long game sets in…

While the planting was a step toward restoring conditions that existed here 150 years ago, it was also a step toward creating habitat for some of the rarest species in the Blue Ridge Mountains. The endangered Carolina northern flying squirrel, cousin to the common southern flying squirrel, is only found in the high-elevation areas of Southern Appalachia, including here in the Black Mountains. As these red spruce trees mature, not only will their branches provide shelter for the squirrels, but the soil amidst their roots will change, providing food for the squirrel. Carolina northern flying squirrels are not nut gatherers, but they do eat truffles. Mycorrhizal fungi are fungi that grow in association with plants, developing a close relationship benefiting both species, often through the exchange of nutrients and water. The truffles the squirrel eats are the fruiting bodies of a mycorrhizal fungus that grows in association with high-elevation conifers. As the squirrels search for and consume the truffles, they inadvertently spread the fungal spores, creating a system where the trees, the squirrel, and the fungus all support one another.

In the even longer term, the planting may benefit two other species protected under the Endangered Species Act (Act). The spruce-fir moss spider, one of only six spiders listed under that Act, and the rock-gnome lichen, one of only three lichens protected under the Act, are also found in the conifer forests of the Black Mountains. Both rely on the high moisture found in these forests, which are often shrouded in heavy fog, and replacing open blackberry thickets, which tend to be hot and dry, with conifer forests, which are cool and moist, is a step toward creating the micro-climate these species require.

Make those micro-climate shifts again and again across the mountain builds a bulwark against climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change . Making spruce-fir forests bigger, healthier, and more connected, makes them more resilient to climate change, helping ensure the forests, and the creatures that depend on it, persist into the future.