Migratory Birds at the Crossroads

From shorebirds to songbirds and wading birds to waterfowl, nearly all migratory birds depend on wetlands at some point in their lifecycle. But these crucial habitats are at risk due to a destabilizing climate and other human landscape modifications, disappearing three times faster than forests. With some wetlands changing at a faster rate than others, there is a pressing need to make more informed, adaptive, and efficient decisions to protect these critical ecosystems and the diverse species that rely on them.

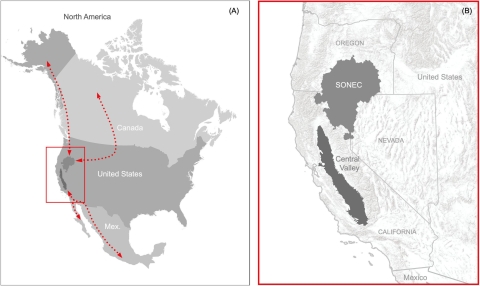

Migrating birds don't recognize borders or boundaries – and neither should our conservation science. Thus, we at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) and our partners manage migratory birds based largely on the routes birds follow as they travel across the continent between their wintering and breeding areas, known as the Flyway system. The establishment of the Flyway system is not only regarded as a precedent setting example of federal and state partnerships, but also helped lay the groundwork for the creation of Migratory Bird Joint Ventures. Established by the visionary 1986 North American Waterfowl Management Plan, Joint Ventures have evolved into a highly successful model for governments and private organizations to cooperate in the planning, funding, and implementation of projects to preserve or enhance habitat. These programs work across flyways to implement conservation plans through adaptive, voluntary and collaborative partnerships. Using the latest science and technology, Joint Ventures not only conserve priority habitats that benefit migratory birds and people, but also contribute to the nation’s climate-resilience strategy.

In both the Pacific and Central Flyways, the Intermountain West Joint Venture (IWJV) has been leading the way in wetland conservation with a revolutionary app created by Patrick Donnelly, USFWS Spatial Ecologist. This constantly evolving tool makes it possible to investigate habitats in real-time like never before, all while fostering collaboration among partners and supporting decision-making efforts at a remarkable flyway scale.

What is WET?

Imagine having a birds-eye view of wetlands, with a peek into how they transform over time. Enter the Wetland Evaluation Tool (WET)! At its core, WET is an interactive data visualizer powered by Google Earth Engine that allows users to evaluate changes and trends in water across different periods—whether it's seasonal shifts or transformations over decades. A beacon of data management success, it collects, organizes, protects, and stores vast amounts of data. Using both satellite imagery and a treasure trove of decades-long data from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), this tool has been fundamental in helping partners across both the Pacific and Central Flyway translate science into action.

It’s not just about water levels; it's about understanding the habitat – the essence of wetlands. WET makes it possible for users to determine the type of available habitats, visualized using three specialized cloud-based computing modules.

The “Surface Water” module offers a dynamic view of surface water over user-defined periods of time to monitor and compare changes in flooded acres. The “Hydroperiod” module provides context about wetland characteristics to see how often and for how long an area has been flooded each year to compare shifts over time or inform habitat management goals for target species. The “Resilience” module helps managers prioritize areas for protection or restoration based on their long-term stability or change over time. Paired with local knowledge, WET provides a new plane of understanding, uniting data streams into a more holistic picture for large-scale conservation efforts. This is data interpretation at its best.

Heart of the Pacific Flyway

One of the IWJV’s highest priority landscapes for conservation, the Southern Oregon Northeastern California (SONEC) region, is of continental scale importance to birds. Spanning multiple counties across Oregon, California, and Nevada, the region hosts a unique mosaic of wetlands, including wet meadows created by irrigated pastures on private lands. This network of wetlands is linked through the Klamath Basin, home of the nation's first refuge established to protect waterfowl: the Lower Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge. What was once the largest area of wetland west of the Mississippi River, the Klamath Basin wetlands are now limited to portions of private lands and six national wildlife refuges in the Klamath Basin National Wildlife Refuge Complex. Today there is neither a lake at Lower Klamath nor the nearby Tule Lake, and recent spatial imaging analysis by refuge staff indicates that almost all of the basin’s wetlands have been lost to land conversion. There is currently so little water that, of the 90,000 acres of protected wetland habitat in the Lower Klamath and Tule Lake refuges, as little as 3,500 acres at Tule Lake remain viable for waterfowl. This water is not only essential to the survival of millions of waterbirds, but also to people, plants, and other wildlife that live there. Farmers need the water to irrigate their lands—some of which provides important habitat for waterbirds— while Tribes also need it to prevent the extinction of culturally important species.

Recognizing the importance of this area, Patrick and the IWJV team got to work using the WET app and were able to document declining wetland habitats across this vast SONEC region quicker and more comprehensively than has ever been done before. WET can also be used to track the footprint of wetland habitat created by seasonal agricultural flooding in SONEC and the Klamath Basin, as well as successful partner conservation efforts in the area.

Connecting the Dots for Sandhill Crane

Wetland complexes in the SONEC region, such as those in the Klamath Basin and Malheur National Wildlife Refuge, provide critical fall migration and breeding habitat for millions of birds, including a significant portion of greater sandhill cranes that winter in the Central Valley. Through a recent multi-year, West-wide tracking effort, Patrick and partners successfully connected the dots between stopover sites for crane migration and gathered significant insights along the way. For the first time, they identified key areas to prioritize for sandhill crane habitat connectivity across both the Central and Pacific flyways. Using WET, they were able to link crane stopover sites to on-the-ground habitat conditions. The researchers discovered that nearly all sites cranes used to nest along this network were on flood-irrigated private lands, wet meadows that mimic the cycles of seasonally flooded wetlands. Thanks to insights from WET, findings like these have helped shape the perception of irrigated agricultural lands and highlight the importance of collaborative conservation across public and private lands to keep flyway connectivity.

Flyway to Flyway

White-faced ibis are another wetland-dependent bird species found in the Central and Pacific flyways. These wading birds depend on diverse wetland types throughout their entire life cycle. The wetlands they rely on are also of high value to numerous other species, especially migratory waterbirds. With this in mind, the IWJV and University of Montana graduate student Shea Coons used the WET app to complete the first long-term monitoring project on ibis breeding habitat in the West and developed a framework for prioritizing wetland conservation that also supports other wetland-dependent wildlife. Using the “surface water” module, they investigated ibis use of nesting and foraging habitat with wetland and surface water trends over a 35+ year period and discovered that rapid drying is impacting wetlands around white-faced ibis breeding colonies in the West. They also discovered that, like sandhill cranes, ibis' colonies have come to depend upon flood-irrigated agriculture on private lands as a surrogate to seasonal wetlands and fringe wetlands that have been lost. These findings further support the need for assessing flyway-scale change and partnerships between private landowners and public land managers to create a complex of wetland systems more broadly. Not only will this science translate into actions that will better conserve sandhill crane and white-faced ibis migration networks, but it may also benefit other wetland-dependent species and foster new collaborative partnerships at the same time.

Improving Biological Outcomes

Monitoring conservation investments like wildlife easements or restoration projects is crucial to determine if outcomes align with habitat or species objectives. Since 1991, the IWJV has worked with partners in SONEC to implement more than 30 North American Wetlands Conservation Act grants to protect, restore and enhance over 167,000 acres of priority wetlands. In 2019, an effort was launched in SONEC to evaluate these and other conservation efforts on private lands to assess their ability to meet Pacific Flyway habitat goals. To investigate, Patrick and his fellow researchers used nearly 50 years of aerial survey data from the Klamath National Wildlife Refuge Complex to reconstruct waterfowl migration patterns. When they combined that information with WET, they found that 67% of conservation investments overlapped wetlands important to northern pintails. Well over half of the continental northern pintail population relies on SONEC during spring migration. The results showed that these birds migrate nearly a month earlier than other dabbling ducks, arriving mid-February before melting snow fills most wetlands. This meant conservation strategies were befitting most waterfowl and shorebirds, but when it came to northern pintails, there was a small gap. Long-term declines in the North American population have increased the scrutiny of changing habitats across the flyway. Recognizing this, private lands biologists from the USFWS Partners Program and their collaborators from Ducks Unlimited and the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service are leveraging access to WET and new waterfowl migration information to improve the targeting of conservation actions that consistently align habitat outcomes with bird needs.

The Future is Adaptive

The science is clear that we need both public and private lands to be functional on the landscape to conserve the thousands of species that depend on them in a rapidly changing climate. WET helps by providing a more efficient way for us to collaborate in real-time and by keeping the information line open for all. It also presents invaluable data-driven insights in a manner that can save time, money and resources for biologists and managers, allowing them to focus more efforts on the ground executing conservation plans. It is transformative, empowering decision makers to visualize, react to present challenges, and anticipate future shifts for adaptive management. Answers to questions that were once considered too complex or too broad in scope are now within reach.

A special nod to Patrick Donnelly, whose dedication, collaborative efforts, and innovation have sown the seeds for a more resilient tomorrow. His pioneering spirit and belief in leveraging technology for the greater good are a testament to the potential of human ingenuity in service of the planet.

Access the Wetland Evaluation Tool (WET)

For more information on how to use the app, contact Patrick Donnelly or Erica Hansen, IWJV

WET Supported Science

- Climate and human water use diminish wetland networks supporting continental waterbird migration

- Synchronizing conservation to seasonal wetland hydrology and waterbird migration in semi-arid landscapes

- Functional Wetland Loss Drives Emerging Risks to Waterbird Migration Networks

- Migration stopover ecology of Cinnamon Teal in western North America

- Migration efficiency sustains connectivity across agroecological networks supporting sandhill crane migration

- Monitoring change across North America’s white-faced ibis breeding colony network; a framework for priority wetland conservation

Intermountain West Joint Venture

- The Call of the Cranes by Intermountain West Joint Venture

- White-faced Ibis & Water in the West by Intermountain West Joint Venture

- Access the WET Data on Sandhill Crane Migration

- Access the WET Data on White-faced Ibis Stopover Habitat