Cold, no breeze, and the air still wet with rain from the day and night before. Perfect weather for spotting waterfowl. The high, repeating honks and cackles of geese ushered in the sunrise at Nestucca Bay National Wildlife Refuge as each backlit group of waterfowl set down in the flooded fields and wetlands. Surrounded by the sounds of a wetland waking up, we set out for the day, iPad, binoculars, spotting scope, and hot coffee in hand.

Most of my days don’t start at dawn in the rain. They usually start at 7:30 a.m., warm and snug in my office in front of my computer. As a public affairs specialist, I have the privilege of talking with folks – the public, reporters – providing transparent and detailed information about the work of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. But today I would be volunteering, assisting refuge staff in their weekly goose count on the refuge and neighboring properties. These surveys take place each year from October to April and have been ongoing since 2003. The results from these goose surveys help refuge biologists better understand how wintering geese use the refuge and neighboring dairy pasture.

The 1,202-acre Nestucca Bay National Wildlife Refuge is located on the Oregon Coast, just south of Pacific City where the Nestucca and Little Nestucca rivers meet and empty into the Pacific Ocean. Established in 1991, the refuge was established to protect and enhance wintering habitat for dusky Canada geese and Aleutian cackling geese and four other subspecies of white-cheeked geese.

“Most people don’t realize that there are 11 subspecies of white-cheeked goose,” said Kylie Blake, wildlife biologist intern. “At Nestucca Bay, we have Western, dusky, and lesser Canada, and cackling geese, including the Taverner’s, Aleutian, and cackling (minima). In the past, a small population of Aleutian cackling geese from Alaska’s Semidi Islands would also winter at the refuge.

Today, we would be counting the six present subspecies as a part of the weekly survey that occurs from October to April each year. Though the species look similar, they have distinct markings and vary in size from the small cackling geese to the much larger Canada geese. Learning to identify those differences at a distance is key to being able to count them accurately. Blake told me that she spent many hours practicing her identification, taking training courses and tests, and learning the nuances of each species. And, of course, spending several hours a week counting them only improves her identification skills.

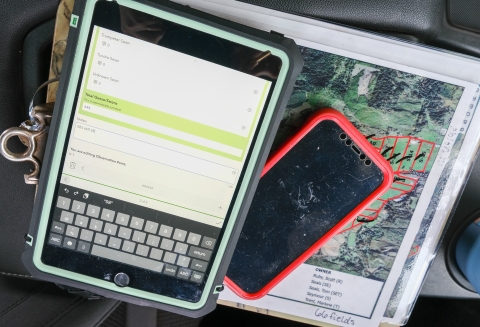

Much to my relief, Blake was the one who identified and counted the geese at each survey location along our mapped-out route. The survey team follows the same route and use the same process for counting each time they head out to count the geese. As the volunteer, my job was to record the number of each species she spotted into an automatic form on the iPad. As we pulled over to count geese in someone’s driveway, Blake noted that the refuge’s lead wildlife biologist, Shawn Stephensen, spent time talking with neighbors and getting permission from landowners to stop and count safely in specific spots.

The result of this systematic planning work and community engagement is a 20-year data set that can be used to understand changes that happen over time. Working together with local landowners and understanding the survey data help refuge managers improve refuge habitat to draw geese away from privately owned fields to those managed by the refuge. The Nestucca Bay Landowners Association has an agreement with the refuge to protect short grass habitat for geese, while also maintaining lands for agriculture. Additionally, since the early 1990s refuge personnel have implemented short grass management strategies on the refuge and planted forage grass species preferred by geese. As a result, more geese are attracted to refuge pastures to eat and rest and less likely to forage on farmers pastures and crops.

When you measure success in conservation, sometimes it looks like a healthy robust species that no longer needs the protection of the Endangered Species Act or because of ongoing work, will not need to be listed. This benefits everyone – wildlife, future generations, and private landowners. In the case of Nestucca Bay, the refuge lands have been an essential part of the recovery of the Aleutian Canada (now cackling) goose and preventing the need for dusky Canada goose to be listed under the ESA. It continues to protect the Semidi Islands Aleutian Cackling goose – which is found in only one other place on Earth, the Semidi Islands Archipelago in Alaska.

One of the benefits of volunteering is the chance to see the refuge and the surrounding area from a new perspective. Spending the day riding in the pick-up truck, you get a lot of seat time with a professional wildlife biologist, learning about the refuge and all the different plants and wildlife that live there. In addition to the wetlands and pastureland, the refuge also features upland forest, coastal prairie, and tideland. Careful management of these habitats protects migratory waterfowl, songbirds, and species listed under the Endangered Species Act, such as coho salmon and the Oregon silverspot butterfly, elk, deer – and, of course, geese.

But don’t take my word for it - Kent Doughty has volunteered for the goose count the last three years, in fact, without his volunteered time from October 2022 – May 2023 the refuge would not have been able to conduct the survey. His dedication inspires me, and hopefully it will inspire you too.

If you are interested in volunteering to help with the goose surveys, or helping with other volunteer projects, and getting to know the refuge and the wildlife it protects, please reach out to refuge staff by phone at 541-867-4550.