With the release of the Sagebrush Conservation Design (SCD) in 2022, rangeland researchers made an extraordinary attempt to map the habitat quality of the imperiled sagebrush sagebrush

The western United States’ sagebrush country encompasses over 175 million acres of public and private lands. The sagebrush landscape provides many benefits to our rural economies and communities, and it serves as crucial habitat for a diversity of wildlife, including the iconic greater sage-grouse and over 350 other species.

Learn more about sagebrush steppe on the scale of the entire biome to evaluate sagebrush condition and prioritize areas for conservation investment. Now, in 2024, a special issue of Rangeland Ecology & Management brings together a suite of new research that leverages the SCD to answer big questions about sagebrush conservation. Learn all about this special issue at the Sagebrush Conservation Gateway.

When you stand within sagebrush habitat, not much may meet the eye at first glance: A dry shrubland seemingly stretches on forever, ending only at distant mountains. There may be no movement but for the breeze. But stand still long enough and you will begin to see that the shrubs are teeming with life. In particular, take note of the small songbirds that dart from place to place.

Many bird species use sagebrush shrubs as nesting sites, as cover from predators, or even as a primary food source. Some species are sagebrush obligates, which means they are dependent on the health of the sagebrush biome to survive. In the face of sagebrush habitat degradation, conservation researchers and managers are tasked with understanding how changes affect these dependent species across the range of the sagebrush ecosystem.

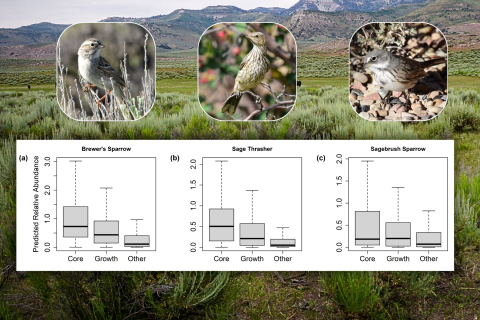

The Sagebrush Conservation Design, released in 2022, looked at the sagebrush ecosystem as a whole and at a massive scale, mapping where the habitat is healthiest and where it is more degraded. Now, a new paper published by a team led by Dr. Alexander Kumar confirms that the Sagebrush Conservation Design’s biome-wide measurement of sagebrush ecological health strongly correlates with long-term population abundance data in three songbird species that are sagebrush obligates: sage thrashers, Brewer’s sparrows, and sagebrush sparrows.

“Sage thrashers had ten times higher abundance in core sagebrush compared to other areas, Brewer’s sparrows were six times as abundant, and sagebrush sparrows three times as abundant,” said Kumar. “We also looked at areas that transitioned from core sagebrush habitat into lower quality habitat over time, and those areas had the strongest population declines.”

By correlating the Sagebrush Conservation Design’s measurement of ecological integrity with long-term data on bird populations, the team was able to provide evidence that shifting the focus to conserving ecosystems, rather than species, will help both the ecosystem as a whole and the many species inhabiting it. In particular, focusing on large intact sagebrush rangelands (also referred to as “core sagebrush areas”) will benefit these imperiled rangeland birds and likely other native wildlife.

Sean Claffey, Conservation Coordinator for the Southwest Montana Sagebrush Partnership (SMSP), remarked that this work has been helpful in prioritizing sagebrush conservation efforts in his region of Montana.

“The Sagebrush Conservation Design and other studies like it are attempting to answer questions at a scale that allows managers to then make big decisions at scale, rather than piecemealing smaller projects together,” said Claffey. “High-level science allows managers to think bigger at necessary scales to impact the entire biome.”

Kumar’s study also found that decreasing tree cover and increasing sagebrush cover seemed to have the strongest positive sagebrush songbird population responses, compared with perennial vegetation cover, annual grass invasion, and human disturbance. This finding makes a lot of sense to Claffey. The SMSP project has successfully removed nearly 50,000 acres of encroaching conifers in southwest Montana since 2017 to improve their local sagebrush habitat.

“As we lose diversity in shrub, grass, and forb species due to conifer expansion in sagebrush, wildlife species populations will inevitably follow. It’s great to have data on bird population trends to show that inherent correlation.”

Kumar feels that this new research supports the Sagebrush Conservation Design’s overall finding that large areas of relatively intact sagebrush are especially valuable as habitat. However, while both Kumar and Claffey thought that biome-wide models like this one can certainly be helpful for conservation project managers, they also agreed that local knowledge and consensus-building are critical to determining best practices within any given community and sagebrush landscape.

“Science like the Sagebrush Conservation Design definitely allows us to plan at a bigger scale, but local science and knowledge are essential,” said Claffey. “We have to get out on the ground as managers in an ecosystem and get familiar with our place to make decisions on an acre-by-acre basis."

If you would like to read the full journal article documenting Kumar and team’s findings, please see “Defend and grow the core for birds: How a sagebrush conservation strategy benefits rangeland birds” in the November 2024 issue of Rangeland Ecology & Management, and visit www.sagebrushconservation.org to access the other journal articles supporting the most recent updates to the Sagebrush Conservation Design effort.