Almost all groups of birds have seen major declines in the last 50 years– almost all, except for waterfowl. As a group, waterfowl have actually increased in population size! So why is that? What is unique about this group of birds, and how can we use that information to build strategies to conserve other types of birds?

Reason #1: Monitoring!

We know, data may not be the most exciting of topics. But the information we have on waterfowl populations is more robust than any other group of species. Our agency has been conducting surveys and monitoring waterfowl populations for close to 70 years!

Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Surveys

One of the most well-known surveys we conduct is the Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey. This survey is also referred to as the Breeding Population Survey –BPOP for short- or the May Survey since it is conducted in May. The May Survey is the largest and longest running wildlife survey of its kind in the world. Since 1955, its results have guided waterfowl harvest and habitat management, and have been used by researchers worldwide to shed light on large-scale dynamics of waterfowl populations. The primary purpose of the survey is to estimate breeding waterfowl populations and track trajectory for most North American duck species, several populations of Canada geese, tundra swans, and American coot, and to evaluate breeding habitat conditions.

The survey is conducted by airplane, helicopter, and ground crews over a 2 million square mile area that covers the principal waterfowl breeding areas in North America, including parts of Alaska, Canada, and the northcentral and northeast U.S. This survey is a cooperative effort of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service) and Canadian Wildlife Service, and a number of states that conduct complementary surveys.

The success of this annual survey is truly a testament to the dedicated survey personnel and pilot biologists of the Division of Migratory Bird Management and the skilled aerial and ground observers from other Service Regions and programs who participate.

The data collected each year during the survey are reported in the annual Waterfowl Population Status Report, which contains current information on breeding population size, habitat conditions, and production, and overall status (population trend, or change from the previous year) of waterfowl species, which wildlife managers use to develop annual harvest regulations to ensure that waterfowl continue to thrive.

Banding Data

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service staff are also involved in both the collection and analysis of bird banding data. Our staff coordinates with banders from various state, federal, private, and tribal agencies in ongoing, annual banding efforts. One example is the Western Canada Cooperative Waterfowl Banding Program which focuses on banding waterfowl throughout the Canadian prairies and Canadian boreal forest in the late summer and early fall.

We then work with our colleagues at the U.S. Geological Survey to develop models that utilize banding and recovery data to predict the impacts of harvest and other types of take, as well as develop an understanding of environmental factors that drive migratory bird populations. Banding data are instrumental in the development Adaptive Harvest Management strategies and are used by biologists to set annual waterfowl hunting regulations.

Information Provided by Hunters

Hunters not only provide financial and public support for wetland and waterfowl conservation, they are a key partner in long-term monitoring, data collection, and science. Waterfowl hunters have participated in one of the longest community science efforts dating back to the 1930s – the reporting of bird bands from the birds they have harvested. One very important use of banding data is to calculate harvest rates, which are used in waterfowl population models to ensure that the harvest of migratory game birds is sustainable and that bird populations remain healthy, so that the hunting can be continued by future generations.

During the 1952-53 hunting season, we began conducting a survey of Federal Duck Stamp purchasers to estimate waterfowl hunter activity and harvest in the United States. That survey was conducted annually through the 2001-02 hunting season, after which it was replaced by a new migratory game bird harvest survey system. In 1992, the Service and state fish and wildlife agencies established the Migratory Bird Harvest Information Program (HIP), which was fully operational nationwide by 1999. This cooperative state-federal program requires licensed migratory game bird hunters to register annually in each state in which they hunt. Each state is responsible for collecting contact information from each migratory bird hunter, asking each of them a series of general screening questions about their/his/her hunting success the previous year, and sending this information to the Service. Each year, we invite a sample of these hunters to participate in the National Migratory Bird Harvest Survey and/or the Waterfowl Parts Collection Survey.

Data from these programs, provided by citizen-hunters, are used to estimate total duck and goose harvest, harvest of individual species, the age and sex ratios of the birds harvested, and where birds were harvested, which helps us understand timing and patterns of migration. This information is critical for both habitat and harvest management: setting season lengths and bag limits, and prioritizing habitat acquisition for waterfowl in the National Wildlife Refuge System.

We report data on hunter and harvest activity, combined with data from the Parts Collection Survey, in the annual Migratory Bird Hunting Activity and Harvest Reports. These reports contain estimates of the harvest of each species or species group, the number of days hunted, the number of active hunters, and the number of birds bagged per hunter in each state for which there is a hunting season for that species or species group.

Related story: Banding Together: the Significance of Waterfowl Bands to Hunters and Scientists Alike

Reason #2: A Legacy of Habitat Conservation!

The long-term strategies for conserving wetland habitat for waterfowl and other wetland-dependent species over the last century have created a strong foundation for conserving all the types of habitat that waterfowl need to complete their entire life cycle.

Probably one of the most important collaborative conservation programs we have, which implements the North American Waterfowl Management Plan, as well as national and international shorebird, waterbird, and landbird partnership initiatives, are the Migratory Bird Joint Ventures. Joint Ventures are a cornerstone of a collaborative effort, considered a model for conservation in the 21st century, using state-of-the-art science and leveraging public and private resources to ensure that diverse habitat is available to sustain migratory bird populations. Joint Ventures have an additional benefit of building capacity of participating partners, making their operations and activities more effective and efficient.

Joint Venture partnerships employ an adaptive, voluntary, and collaborative approach to wildlife and habitat conservation which provides many benefits to migratory birds, wildlife, and people. Since their inception, Joint Ventures bring industry, local municipalities, regulators, policy makers, restoration practitioners, and local community members together to create and implement habitat projects and collaborative conservation actions.

One of the foundational systems that helped lay the groundwork for the creation of the Joint Ventures is the Flyway system – a collaboration between each state, provincial, and territorial agency within that Flyway –that has been a cornerstone of wildlife conservation in the United States for decades. The establishment of the Flyway system in the 1950s has been instrumental in the conservation of waterfowl populations. The collaborative effort has led to the implementation of long-term monitoring programs, such as the May Survey referenced earlier, that are critical to understanding waterfowl ecology and implementing harvest regulations that ensure the long-term health of waterfowl populations while providing recreational opportunities for the American public. This partnership has supported a broad array of research that has increased our understanding of waterfowl ecology, harvest management, habitat management, and human dimensions aspects of wildlife conservation.

Another program that has had a huge role in conserving bird habitat is the North American Wetlands Conservation Act (NAWCA) program. Wetlands Conservation grant projects increase wetland bird populations and habitat, while supporting local economies and activities such as hunting, fishing, and bird watching. Wetlands protected by NAWCA grants provide valuable benefits such as flood control, reduced coastal erosion, improved water and air quality, and recharging ground water. In the past three decades, the NAWCA grant program has funded over 3,200 projects totaling over $2 billion in grants! And more than 6,600 partners have contributed another $4 billion in matching funds to benefit over 31 million acres of habitat.

Reason #3: Everyone Can Be a Part of Conservation!

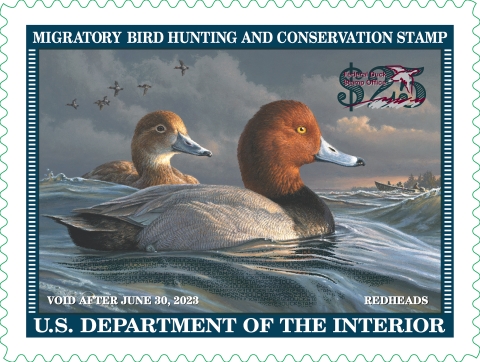

What’s the easiest way for every single person to help conserve waterfowl habitat??? By purchasing your very own Federal Duck Stamp! Of every dollar spent on a duck stamp, 98 cents of the purchase goes directly to acquiring and protecting habitat for ducks, geese, swans and other wildlife as part of the National Wildlife Refuge System. Since 1934, sales of this stamp have raised more than $1.1 billion to protect over 6 million acres of wetlands habitat on national wildlife refuges around the nation. Waterfowl are not the only species that benefit from wetland habitat preservation. Thousands upon thousands of shorebirds, wading birds, raptors, and songbirds, as well as mammals, fish, native plants, reptiles, and amphibians rely on these landscapes as well. In addition, other Birds of Conservation Concern use wetland and connected upland habitat to feed, breed, migrate and rest, including species like the wood thrush, golden-winged warbler, reddish egret, and long-billed curlew. That’s why we encourage everyone - birders, outdoor enthusiasts and fans of national wildlife refuges- who understands the value of preserving some of the most diverse and important wildlife habitats in our nation to buy a duck stamp and join the millions of Americans who want to put their stamp on conservation!