“Thousands have lived without love, not one without water.” ~ poet W.H. Auden

We all know the importance of water to life on Earth. Mike Higgins knows it even better.

“Water covers more than two-thirds of Earth’s surface,” he says. “But less than four percent of Earth’s water is freshwater. If you add up all the freshwater in all the rivers and lakes, it amounts to only 0.0072 percent of all the water in the world by volume. Most freshwater is locked up in ice sheets and glaciers, and occurs as groundwater. It really is a finite, precious resource.”

Higgins coordinates with a team of 13 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service specialists who monitor the quality and flow of that precious resource at and near national wildlife refuges, wetland management districts and national fish hatcheries.

One team member is Minnesota-based hydrologist Josh Eash.

“I like the challenge of studying different river systems, each with their own personality. Some are subdued and placid, while others are more unruly and mischievous,” Eash says. “Whether I'm at work or a backyard barbecue, conversations often turn to water-related issues. This gives me the sense that I’m doing something that really matters.”

A Complicated Job

Efficiently managing water on public lands is more complex than you might think.

Guided by Higgins, specialists at the National Wildlife Refuge System’s Natural Resource Program Center in Colorado and around the country have spent more than a decade developing an inventory and assessment database that houses information about water resources important to Fish and Wildlife Service-managed lands.

That database helps safeguard water quality by providing individual refuges, hatcheries and other lands with information needed to make sound on-the-ground decisions related to:

- Acquiring, protecting and maintaining water rights

- Identifying ideal habitats for wildlife through detailed mapping of wetlands, lakes and streams

- Maintaining the right amount and quality of water for threatened and endangered species

- Restoring refuge stream and wetland habitats

- Monitoring water levels in underground aquifers — especially in the West

- Reacting to permafrost thaws and higher water temperatures in Alaska and to extreme precipitation and drought elsewhere as climate changes

- Monitoring emerging concerns about harmful microplastics in water

- Managing refuge water in-flow and out-flow budgets

- Showing precisely how water moves throughout refuges

“I love using my unique and niched expertise to assist refuges on an issue that is so fundamental to their conservation mission,” says Rachel Esralew, a California-based Fish and Wildlife Service hydrologist. “Every day I see examples of hydrologic data and information being used to protect refuge water assets and help refuge managers make informed decisions. It brings me joy to see data being put to good service.”

Communities Benefit

Not only do fish, wildlife, birds and plants benefit from sound U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service water management practices, so do people in neighboring communities.

National wildlife refuge wetland vegetation improves overall local water quality by filtering out contaminants, pollutants and other impurities. During floods, refuge wetlands absorb millions of gallons of water that otherwise would inundate nearby cities, towns and private farmland. During hurricanes, wetlands at coastal refuges improve storm resiliency by cushioning the blow of seawater surges. Proper water management can help improve insect control and erosion control. Refuge wetlands can help to recharge groundwater and aquifers.

Fish and Wildlife hydrology data also can help states and municipalities monitor water quality.

Maintaining high-quality water in proper quantities makes great outdoor recreation possible, too. Each year millions of people hunt, fish, hike, paddle, view wildlife or take nature photos at refuges. All these activities boost local economies and offer visitors a chance to unplug from the stresses of modern life.

Putting the Data to Use

The database is available for use by managers, wildlife biologists, maintenance workers, technicians, engineers and other conservation professionals at refuges. It can help them ensure dam safety, protect rare spring species, improve water management infrastructure, reduce impacts of invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

Learn more about invasive species , identify and remove barriers that prevent fish and other aquatic animals from moving freely, and — in Alaska especially — conserve river systems that provide food and other subsistence to local villagers.

A Remarkable Resource

To Fish and Wildlife Service hydrologist Chris Shaffer, the most amazing thing about water is its landscape-forming capacity — the ability of water, in the form of glaciers from the last Ice Age, to carve beautiful features as the glaciers receded and the power of flowing water to cut canyons over millions of years.

Water’s duality fascinates hydrologist Jasper Hardison. “It transforms the landscape,” he says, “yet you can scoop a handful of water out of the river.”

Hydrologist John Faustini is awed by the fact thatwater helps redistribute heat across the surface of the Earth – in particular, from the equator toward the poles – as clouds and ocean currents.

“The unique properties of water are what keep the equator from being uninhabitably hot and the higher latitudes from being uninhabitably cold, for the most part,” Faustini says. “Those properties are also responsible for the generally milder climates of coastal versus inland areas. So water is good for a lot more than just quenching your thirst.”

Happy to Be Covered in Mud

Noel Turner exemplifies the spirit — and the future — of U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service hydrology at national wildlife refuges, wetland management districts and national fish hatcheries.

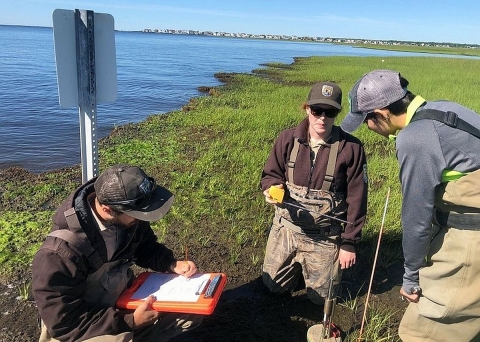

“A cubicle job was not for me,” she says. “I tried it. Even though I am often covered in mud while in the field, I’m much happier there than in the office.”

Just four years out of college, Turner is a hydrologist based at Cape May National Wildlife Refuge in New Jersey. She grew up on a farm within the Chesapeake Bay watershed.

“We were taught the importance of buffers along streams to protect water quality,” she says. “As I got older, I could see how important clean water is to us humans as well as to all the wildlife and aquatic life that is so valuable. We are generally lucky in the United States. We have legal battles over water in the West, and they are starting to occur in the East. But some countries don’t have clean water at all or might wage wars over water. I hope the work that I do will help keep our water clean and available into the future.”