Over the last 150 years, the effects of human activities such as agriculture, mining, damming, logging, and overfishing have led to declines in Pacific salmon species. For decades, efforts have been made to help salmon persist through the challenges they faced. Now climate change climate change

Climate change includes both global warming driven by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases and the resulting large-scale shifts in weather patterns. Though there have been previous periods of climatic change, since the mid-20th century humans have had an unprecedented impact on Earth's climate system and caused change on a global scale.

Learn more about climate change is adding to the suite of challenges threatening the long-term viability of salmon and the cultures, traditions and economies of the communities that depend on them. In the Pacific Northwest, the populations of many salmon species have declined significantly, with some protected under the Endangered Species Act. In Alaska, a place with historically healthy salmon runs, the decline of some runs has caused tremendous hardship and concern.

The Five Species of Pacific Salmon

Each has different habitat requirements and life histories. Some spawn in mainstem rivers, some in small streams, some in lakes. Some spend years in freshwater, while others spend only months. All require cool, clean, connected rivers and healthy ocean conditions.

Coho (Oncorhynchus kisutch

Weight: 8 to 12 lbs. Length: 24 to 30 inches

Coho Salmon begin life in freshwater tributaries along the Pacific coast. Of all the Pacific salmon, Coho have the longest freshwater residency (sometime up to four years). The juveniles migrate to the ocean in the spring. The remainder of the life cycle is spent foraging in estuarine and marine waters of the Pacific Ocean. The adults return to spawn in the river where they hatched, usually in the fall (September to December).

Pink (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha)

Weight: 3 to 5 lbs. Length: 20 to 25 inches

Pink Salmon have the shortest lifespan of all Pacific salmon, completing their life cycle in just 2 years. They spawn in freshwater close to marine waters and sometimes spawn in the brackish water. When the fry emerge, they immediately migrate to estuaries. The shorter journey increases the odds of survival.

Sockeye (Oncorhynchus nerka)

Weight: 4 to 15 lbs. Length: 18 to 31 inches

Sockeye Salmon prefer to spawn in river systems that have a lake. In addition to spawning in rivers and streams, it’s common for them to spawn on lake shores. Most populations of Sockeye Salmon are anadromous. Fry that hatch in rivers and streams generally migrate to the ocean soon after leaving their redd (nest). Fry that hatch in lakes spend 1–3 years in freshwater before migrating to the ocean. Kokanee Salmon are Sockeye that do not migrate to the ocean and instead live their entire life in freshwater systems. They rarely grow longer than 18 inches.

Chum (Oncorhynchus keta)

Weight: 6 to 15 lbs. Length: 24 to 28 inches

The most widely distributed of all Pacific salmon species, Chum Salmon can be found in most coastal streams from Arctic Alaska to San Diego, California. Chum fry do not spend more than a few days in freshwater. Once they are strong enough to swim, they migrate to estuaries where they spend several months before heading out to the open ocean for the next 3–4 years.

Chinook or King Salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha)

Average Weight: 40 lbs Average Length: 27 inches

Chinook Salmon are the largest of the Pacific salmon species. They have been recorded weighing more than 100 lbs. and as long as 50 inches. The maximum reported age for Chinook Salmon is 9 years. Chinook spend the longest time at sea, which enables them to reach sizes capable of migrating upstream long distances and digging deep redds in powerful rivers.

A Brief History of the Decline

Since Time Immemorial

Long before human life, there were salmon. By some estimates, the fish first appeared in Alaskan and Pacific Northwest waters between 4 and 6 million years ago—since time immemorial. For much of the species’ time on earth, supported and fished sustainably by Indigenous stewards, the robust Pacific salmon has thrived in clean, congruous ecosystems.

1875 The Earliest Warning

Shortly after the first settlers arrived in the Pacific Northwest, in as early as 1875, the U.S. Commissioner of Fisheries identified overfishing, damming, and habitat degradation as salmon’s three main threats.

1894 A Declining Population

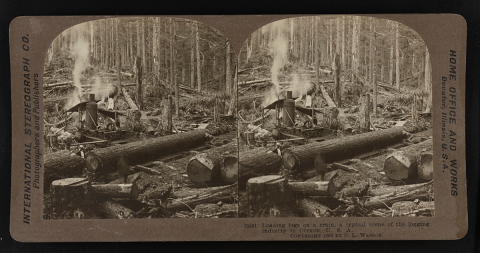

Agriculture, logging, mining, and associated infrastructure like transportation networks further reduced and harmed available habitat around the Puget Sound and Oregon. In 1894, the first reports of a declining salmon population in Washington state were issued.

1900 A Booming Salmon Economy

By the turn of the century, a growing commercial salmon industry included the operation of more than 200 salmon canneries along the coast from California to Alaska.

1930—1970 The "Big Dam Era"

Hundreds of dams were built to collect water for cities and towns, irrigation and hydropower, blocking salmon migration to and from the ocean.

1990—1993 Populations Continue to Fall

In 1990, after nearly a century of barriers, Coho Salmon populations continued to dwindle along the west coast. The following year, the Federal government listed Snake River Sockeye Salmon as endangered. In 1992, Snake River summer and fall Chinook Salmon are classified as threatened.

1997—1998 Disaster Declarations in Alaska

The state’s first fishery disaster declaration was issued for Bristol Bay and the Kuskokwim River, followed by another in 1998 for the Yukon River.

TODAY Climate change compounds challenges

As NOAA Fisheries considers nine populations of salmon either threatened or endangered, the efforts to recover them and support other populations face many challenges that are now compounded by climate change. Some of the effects of climate change include alterations in the timing and magnitude of snow melt, extreme floods and droughts, increasing water temperatures, invasive species invasive species

An invasive species is any plant or animal that has spread or been introduced into a new area where they are, or could, cause harm to the environment, economy, or human, animal, or plant health. Their unwelcome presence can destroy ecosystems and cost millions of dollars.

Learn more about invasive species , rising sea levels, and changing shorelines and ocean current patterns.

The Ecological Importance of Pacific Salmon

Pacific salmon are essential ecologically. They are a keystone species meaning their presence (or lack thereof) impacts the health of the entire ecosystem. Salmon are an essential food source for many species, including humans. Even the plants surrounding rivers and streams where salmon spawn benefit as salmon carcasses decay and release their ocean-derived nutrients into the environment.

Salmon are considered to be an indicator species because the health of salmon tells us a lot about the overall health of the environments in which they live. When things get out of balance, their declining populations let us know we need to be paying closer attention to the broader ecosystem. They also let us know that other species who depend on them or need similar ecological conditions to survive (I.e., cold, clean water) are likely struggling, too.

The Cultural Significance and Economic Benefits of Salmon

As is happening more often, when salmon fail to return from the ocean to inland rivers where they spawn in numbers that allow for adequate harvest—cultures, traditions, and economies suffer.

Since time immemorial, Indigenous peoples have lived with and from Pacific salmon. Many tribes refer to themselves as “Salmon People” because their creation stories and traditions are intrinsically shaped by their enduring relationships with the fish. The nutritional and spiritual health of tribes are linked, in turn, with the health of sacred salmon.

"The salmon was put here by the creator for our use as part of the cycle of life. It gave to us, and we, in turn, gave back to it through our ceremonies…Their returning meant our continuance was assured because the salmon gave up their lives for us. In turn, when we die and go back to the earth, we are providing that nourishment back to the soil, back to the riverbeds, and back into that cycle of life." ~ Carla HighEagle, Nez Perce

Climate Change Threatens the Future of Salmon Fisheries

In 2013, an ocean heatwave known as the Blob began to form off the West Coast. Ultimately, it extended from the Gulf of Alaska to Baja California and lasted for several years. With ocean temperatures up to 7 degrees Fahrenheit above normal, the entire ocean ecosystem was impacted. Dozens of fishery disaster declarations were issued for West Coast fisheries, including for salmon.

In the summer of 2019 in Alaska, with record heat and drought, a study led by the U.S. Geological Survey found that the heat and drought conditions coincided with widespread premature death in salmon. In January 2022, the Commerce Department announced multiple fishery disaster determinations for Alaska that occurred in 2018 to 2021 primarily for salmon fisheries. The determinations paved the way for funding to be distributed to fishermen and their crews, processors, and for research.

In early April 2023, the Pacific Fishery Management Council announced its recommendations for the 2023 ocean commercial and recreational salmon fishing season for the Pacific west coast with significant closures for the southern portions of the coast to conserve numerous salmon stocks. The Council's Executive Director Merrick Burden acknowledged the negative impact on people who participate in these fisheries and the small businesses that support them.

In Alaska, the state's Department of Fish and Game closed sport fishing for Chum and Chinook Salmon in both the Yukon and Kuskokwim rivers for the 2023 season and announced that it will be implementing closures or restrictions of the Chinook, Chum and Coho salmon subsistence fisheries and does not expect to open commercial fishing for these species. The state also has announced heavy restrictions on sport and personal-use Chinook Salmon fishing around the Cook Inlet region following years of below-expected salmon returns.

As the impacts of climate change continue to take hold, the fishing and seafood industry face a challenging future—by the end of the century, catches in fisheries are expected to decline by 21–24 %.

Efforts to Save Salmon Bring Hope

Knowledge-holders, scientists, volunteers, municipalities, Tribes, state, and federal agencies including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, are collaborating on a variety of creative, sustainable projects to restore the Pacific salmon’s freshwater habitats with some projects having the added benefit of improving the environment's resilience to climate change, while others are being done in response to climate change.

“I absolutely believe our fish will come back. But we all need to work together in communities all along the Klamath River to look for solutions to the impacts of climate change. Communication is very important; we need to put ecology first and economy second. We can make a difference, but we all need to come together and act now.” Russell “Buster” Attebery, Karuk Chairman

Explore a few of the projects below.

Restoring Salmon Habitat of the Yuba River

In an area of the lower Yuba River that was heavily modified by hydraulic gold mining in the early 1900s, work is being done to restore the natural flow and flood regime of this section of the river and increase and improve salmon rearing habitat, which will allow juvenile salmon to get larger before migrating to the ocean and improving their chances of reaching the ocean. Recent models for the Yuba River showed how certain sections of the restored habitat may be particularly resilient to extreme weather events and temperature rise brought on by climate change.

Restoring Gravel for Spawning Salmon on the Sacramento River

In California, historic mining operations have led to the removal of thousands of tons of gravel from riverbeds, and the construction of dams and bridges continue to alter waterways. This large-scale loss of riverbed has had profound impacts on salmon, who lay and bury their eggs in gravel nests.

But over the last decade, projects in California, supported by cities, townships, and federal partners including the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, are contributing to a significant chapter in the state’s history of salmon-focused work, says Aurelia Gonzalez, a project manager with Sacramento River Forum. Gravel restoration efforts in the American, Yuba, Mokelumne, Sacramento, and Merced rivers are providing clean spawning beds throughout the state.

Restoring Salmon Habitat of the Trinity River

The Yurok Tribe received a grant of $4 million from the California Department of Fish and Wildlife in April 2023 and $735,000 from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 2022 for the largest fish habitat restoration project in the history of the Trinity River. The Trinity, which is the largest Klamath River tributary, has been impacted by dams, drought and water diversions that have reduced salmon and steelhead spawning habitat resulting in severely declining runs.

The project will remove 500k cubic yards of historic gold mine tailings and restore about 32 acres of floodplain, wetland and riparian riparian

Definition of riparian habitat or riparian areas.

Learn more about riparian habitat that will increase juvenile salmon and steelhead habitat by up to one-thousand percent within the targeted area.

This project and the following two that are being carried out by Karuk and the Resighini Rancheria nations respectively are part of a broader restoration effort being done in the Klamath basin.

Researching Climate Change Impacts on Klamath River Spring Chinook

In 2022, the Karuk Tribe received over $325,000 from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in Bipartisan Infrastructure Law Bipartisan Infrastructure Law

The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (BIL) is a once-in-a-generation investment in the nation’s infrastructure and economic competitiveness. We were directly appropriated $455 million over five years in BIL funds for programs related to the President’s America the Beautiful initiative.

Learn more about Bipartisan Infrastructure Law funding to monitor water quality and the distinct run of adult spring Chinook salmon in the Mid-Klamath River Basin. Through community support for fisheries conservation, funds will be used to provide insights into how Ishi Pishi Falls functions in migration for this culturally significant run of Chinook as it edges closer to extinction. Understanding the salmon and water quality in this reach of the Klamath River will help build an understanding of climate change impacts on these fish.

Opening Salmon Access to Klamath River Estuary

In April 2023, the Resighini Rancheria was awarded $2 million through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service National Fish Passage Program and $600,000 from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law in 2022 to put towards replacing two undersized culverts on Waukell Creek and its tributary Junior Creek on the Resighini Rancheria in northern California.

These two waterways are part of the network of Klamath River Estuary sloughs and tributaries that provide vital freshwater rearing and winter refugia habitats for threatened juvenile Coho Salmon, steelhead trout, and coastal cutthroat trout.

The Tribe has been working to implement this project for over ten years and is close to securing all necessary funding. Once completed, this project will maximize fish passage fish passage

Fish passage is the ability of fish or other aquatic species to move freely throughout their life to find food, reproduce, and complete their natural migration cycles. Millions of barriers to fish passage across the country are fragmenting habitat and leading to species declines. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's National Fish Passage Program is working to reconnect watersheds to benefit both wildlife and people.

Learn more about fish passage opportunities between the Klamath River Estuary and critical salmonid habitats on the Rancheria.

Reconnecting Salmon to Habitat: The Salmon SuperHighway

There’s a highway along the Oregon coast that you won’t find on a map. It’s one of the state’s most used highways, with travelers crowding 10-wide at times. This highway connects farmers and scientists, loggers and conservationists, people and fish. It’s the Salmon SuperHighway: a strategic, comprehensive effort across a six-river landscape to reconnect fish populations with the habitat they need by updating road crossings and other barriers, while also addressing flooding and road damage. When complete, it will span 178 river miles, reconnecting a 940-square-mile landscape on the north Oregon coast that feeds Tillamook and Nestucca bays.

Saving Salmon from Extreme Heat

In late June of 2021, with record breaking temperatures over 100 degrees Fahrenheit, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Tribal partners worked together to save millions of the Columbia River Gorge Hatchery Complex's salmon from extreme heat. Service staff and Tribal partners at the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs and Yakama Nation safely transferred 348,000 spring Chinook salmon from Warm Springs National Fish Hatchery and released another 7.15 million juvenile upriver bright fall Chinook salmon eight days ahead of schedule before river temperature hit the danger range.

Future-Proofing Kalama Creek Hatchery

At the Nisqually Indian Tribe's Kalama Creek fish hatchery, biologists hope that multi-million-dollar investments in water reuse capacity and infrastructural improvements will help salmon thrive amidst reduced flows, warmer waters, and unpredictable rainfall.

Piloting Circular Tanks to Conserve Water

When it was built in 1940, the Leavenworth National Fish Hatchery was the largest in the world, established to compensate for anadromous fish losses above Grand Coulee Dam. More than 80 years later, the hatchery is preparing for a future of altered flows, temperature, and composition of Icicle Creek and the surrounding landscape. They are currently implementing a water-saving pilot project using Partial Recirculating Aquaculture Systems (PRAS) that recondition and reuse water for rearing fish.

Improving and Increasing Spawning Habitat with Engineered Log Jams

In forests around Lake Quinault, 20th century logging removed nearly all mature woodland from the upper Quinault Valley, leading to bank erosion and widened floodplains. This, combined with historically low water levels and warmer waters, has greatly reduced salmon spawning habitat in the Quinault River. But over the past 15 years, more than 50 log jams have been installed in the river, stabilizing the floodplain and forming natural collections of substrate and deadwood debris—creating cool pools and side channels for salmon to swim through and spawn.

Adapting to a Changing Climate

On the Olympic Peninsula at the Quinault and Makah National Fish Hatcheries and the Makah Indian Tribe’s Hoko Falls Hatchery, managers share their observations, concerns, adaptations, and outlook for hope for managing the changes in climate that have affected the precious resources of salmon, steelhead, and more.

Installation of Eight Fish-Friendly, Flood-Resilient Bridges

When glaciers melt—which is occurring more rapidly due to climate change—their weight is lifted off the ground, causing land to rise, a phenomenon called isostatic rebound. This was occurring at the Good River in Gustavus, Alaska, situated in the ancestral homelands of the Hunga Tlingit. The culvert there became perched, preventing fish from accessing the river upstream. In 2022, a fish-friendly bridge replaced this culvert, capping off a decade-long effort to outfit the Good River’s tributaries with eight fish-friendly bridges.

Opening Access to More Than 70 Miles of Salmon Habitat

A two lane, 100-foot bridge is being installed on the Little Tonsina River in the Valdez-Cordova Borough to replace an undersized, double barrel culvert. The bridge, which has been designed based on the Service's guidelines for construction of road-stream crossings that are flood resilient and fish friendly, will open 70.4 miles of relatively pristine Coho and Chinook salmon spawning and rearing habitat. These waters eventually meet Alaska’s Copper River, home to what many people consider one of the world’s finest sources of salmon.

A wide variety of partners, including the Chugach Alaska Native Corporation, have been involved and contributed to this project.

Investment in the Resilience of Ecosystems and Communities

In the spring of 2023, The Department of the Interior announced the Gravel to Gravel Initiative—coordinated through the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Bureau of Land Management — to partner with Tribes, Indigenous leaders, other agencies, and communities to enhance the resilience of the region’s ecosystems and communities through transformational federal, philanthropic, and other investments. The initiative is in response to the climate crisis and will develop projects to future-proof salmon habitat and surrounding ecosystems.

Here are some things you can do to help salmon:

- Use the bus, carpool, ride your bike, or walk whenever and wherever you can! This keeps the air and water clean for all of us, including salmon.

- Limit your shower time and turn off faucets/showers when you are not using them. When you conserve water, you leave more water for the salmon.

- Storm drains go right into our rivers, lakes, and wetlands. Wash your car on the lawn to prevent soap from going into storm drains. Never dump liquids with chemicals down storm drains! Salmon cannot live in polluted water.

- Conserve electricity by turning off the lights when you are not using them. Conserving electricity means less need for dams and more salmon.

- Stay on trails when hiking or riding. Never ride your bike or off-highway vehicle in creeks or fragile wetlands that are home to salmon.

- Compost and then use the compost instead of fertilizer for your garden and plants. This helps reduce waste and keeps chemicals and fertilizers out of our rivers and streams.

- Plant native plants. Native plants are better adapted to the environment, so they need less water and do not need fertilizer or pesticides. This saves water for the salmon and keeps the rivers healthier.

- Be careful what you flush down your toilet or sink. Only flush biodegradable products. Avoid chemicals and try to avoid using the garbage disposal. Anything you flush or drain makes its way to our streams and rivers.

- Use low-flow toilets and showers or stick a brick or jug of water in your toilet tank to decrease the volume of water it uses. This can save ½ gallon of water per flush, which leaves more water for salmon.

"New Challenges in the Struggle to Save Pacific Salmon" also available in a StoryMap format!

Co-Author: Andrea Medeiros, Public Affairs Specialist, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Alaska Region

Co-Author: Christian Thorsberg, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Communications Fellow, Great Basin Institute

Co-Author: Leah Schrodt, Conservation Communication Specialist, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Region

Co-Author: Susan Sawyer, Klamath Basin Public Affairs Officer, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Southwest Region

Co-Author: Lena Chang, Public Affairs Officer, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Pacific Region